It is well known that minorities receive disproportionately harsh punishments compared to whites from the justice system, and this also holds for juvenile minorities. In new research which looks at 75,000 sentencing cases in Florida, Joshua Cochran finds that minority youth are also less likely to receive sanctions that are oriented towards rehabilitation, meaning that they miss out on the benefits of such treatment. He writes that this decreased emphasis on rehabilitation may be due to juvenile courts’ perception that minority youth are less likely to benefit from such interventions.

It is well known that minorities receive disproportionately harsh punishments compared to whites from the justice system, and this also holds for juvenile minorities. In new research which looks at 75,000 sentencing cases in Florida, Joshua Cochran finds that minority youth are also less likely to receive sanctions that are oriented towards rehabilitation, meaning that they miss out on the benefits of such treatment. He writes that this decreased emphasis on rehabilitation may be due to juvenile courts’ perception that minority youth are less likely to benefit from such interventions.

Studies of U.S. sentencing practices have consistently identified an upsetting trend: minority citizens receive disproportionately harsh punishments compared to white citizens. We see this in both the adult and juvenile systems. However, for the juvenile system, there is another concern. In new research with my colleague, Daniel Mears, we find that the juvenile system provides a unique and additional pathway to disparate treatment. Minority youth are not only more likely to receive the more punitive sanctions; they are less likely to receive rehabilitation-oriented sanctions as well

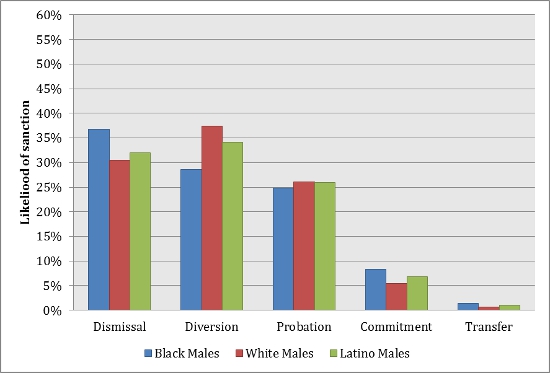

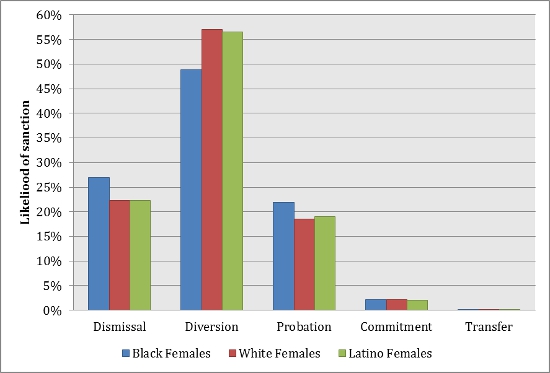

We analyzed a year’s worth of juvenile sanctioning outcomes, almost 75,000 cases, in Florida. We accounted for a range of factors, including prior record and offense severity. The main findings are illustrated in Figure 1 below. Specifically, the findings revealed three interesting patterns:

- Minority youth, especially Black males, have a higher likelihood than Whites of receiving probation, juvenile detention, and to be transferred to adult courts. These sanctions—and in particular, detention and adult transfer—are the more punitive options available in the juvenile system.

- Minority youth are less likely than Whites to receive diversion. Diversion is traditionally a rehabilitation-oriented sanction. It includes a range of intervention and treatment options.

- Minority youth are substantially more likely than Whites to be dismissed, with no sanction or programming at all.

Figure 1 – Predicted likelihoods of sanction type

Panel A. Males

Panel B. Females

Note: Results from multinomial logistic regression.

What makes the third pattern, that minorities are more likely to be dismissed, a problem? In the adult system, a higher rate of dismissals would be seen as leniency, one that, in this instance, benefits minority offenders. The adult system, however, is substantially different than the youth system. The primary goal of the adult punishment system is murky at best, and in the contemporary era is not solely or substantially focused on rehabilitation. If you were to survey a sample of lawyers, judges, and policymakers about the goals of adult punishments, my betting money is that responses range widely, and include incapacitation, retribution, rehabilitation, and more.

In the juvenile system, the picture is much clearer. Juvenile courts are more squarely focused, at least in design, on rehabilitation. The system’s central goal is to save the children, best it can. It is this inherent rehabilitative philosophy that makes this pattern of findings problematic. The results suggest that courts are less likely to “divert” minority youth—that is, enroll them in less punitive, more rehabilitation-oriented sanctions. (Diversion, and the programming options it typically entails, very much epitomizes the court’s mission to “save” youth.) At the same time, minority youth are more likely to be dismissed than White youth. If, in practice, diversion is truly rehabilitative, than minority youth who are dismissed are missing out on benefits provided by treatment and programming.

What causes these disparities, or, disproportionalities? Researchers have posed a range of explanations. Prejudices and implicit biases held by court actors, community and neighborhood effects, and patterns in police activity, among others, are all possibilities. Those explanations, though, are typically used to understand increased severity of punishment for minorities. What explains decreased rehabilitation? This pattern is less well understood. One possible explanation may lie in court actors’ perceptions of who can be saved. Meaning, juvenile courts may simply perceive that minority youth are less treatable, or “rehabilitatable,” than whites.

This idea is based partly on prior examinations of juvenile probation officers’ written assessments of juvenile offenders. Those written records revealed that officers perceived minority youth as less amenable to treatment, and officers feared that interventions would be less successful for those youth. Courts may be unwilling to enroll minority youth in programs and services if the chances of failure are perceived to be too high.

Perceptions of reduced treatability of minority youth may stem from a range of sources. It may stem, for example, from the realistic observation that minority youth disproportionately come from impoverished communities or otherwise adverse social backgrounds, where the chances of or opportunities for criminal activity are higher. By contrast, youth who come from more stable communities or families may be viewed as a lower risk investment for rehabilitative intervention. Ironically, though, it is likely those youth from the worst neighborhoods that have the most to gain.

There are other explanations that should be explored. In a recent interview, experts with the Florida of Department of Juvenile Justice proposed a different, and quite plausible, explanation of our findings. They wondered whether the increased rate of dismissals for minority youth stems from an increased rate of frivolous referrals (the juvenile version of criminal charges) for minorities. Meaning, minority youth may be on the receiving end of baseless charges more often than their white counterparts. In this case, the increased rate of dismissals for minority youth would be warranted and necessary. This is a plausible and similarly troubling possibility, and one that should be evaluated further.

Identifying racial and ethnic disproportionalities in criminal sentencing is a challenging and important research puzzle. Efforts to solve this puzzle highlight the broader need to develop a better understanding of actual punishment impacts. Punishment impacts—such as whether punishment rehabilitates or deters or causes harms—are important in their own right, and for what they can tell us about unfairness in the system. For example, is juvenile diversion, across states and jurisdictions, truly a rehabilitative experience for youth? If it is, it further emphasizes the importance of studying these dual pathways to disparities (i.e., more severity and less rehabilitation for minorities). Alternatively, if diversion is not successful in rehabilitation, it raises broader questions about the overall effectiveness of the juvenile system and its efforts to “save the children.”

This article is based on the paper “Race, Ethnic, and Gender Divides in Juvenile Court Sanctioning and Rehabilitative Intervention,” by Joshua C. Cochran and Daniel P. Mears, published in the Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency.

Featured image credit: Shawn Calhoun (CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1G9A7nE

_________________________________

Joshua C. Cochran – University of South Florida

Joshua C. Cochran – University of South Florida

Joshua C. Cochran is Assistant Professor in Criminology at the University of South Florida, and studies punishment, sentencing, and theories of crime. He was recently awarded the American Society of Criminology’s Division on Corrections and Sentencing Dissertation Award for his doctoral thesis focused on imprisonment and the implications of inmate social ties. Cochran is the author, with Daniel P. Mears, of Prisoner Reentry in the Era of Mass Incarceration (Sage Publications). You can follow him on Twitter: @JoshuaCCochran.