The majority opinion is the main vehicle for policy-making for state and federal courts. Longer opinions usually indicate a more detailed explanation of the decision of the majority. But is the length of these opinions influenced by whether justices are appointed or elected? In new research Meghan E. Leonard and Joseph V. Ross find that while the length of these opinions is not directly affected by how judges are selected, appointed justices write longer opinions when a separate opinion is filed or when the majority opinion author is not randomly selected, as compared to states where justices are selected through contestable elections.

The majority opinion is the main vehicle for policy-making for state and federal courts. Longer opinions usually indicate a more detailed explanation of the decision of the majority. But is the length of these opinions influenced by whether justices are appointed or elected? In new research Meghan E. Leonard and Joseph V. Ross find that while the length of these opinions is not directly affected by how judges are selected, appointed justices write longer opinions when a separate opinion is filed or when the majority opinion author is not randomly selected, as compared to states where justices are selected through contestable elections.

The most consequential work of an appellate court happens behind closed doors as judges and justices draft their opinions. In state supreme courts, a majority opinion contains not only the justification for the case before the court, but also guidance to all other judges in the state on the legal questions presented in a case. Given that a majority opinion is a court’s main vehicle for policy-making, the opinion-writing process is central to understanding the work of American courts.

Researchers have previously considered the complexity, readability, and clarity of a court’s opinions, as well as the sources cited to justify the decision. In new research, we focus on the length of opinions as a rough indicator of both the thoroughness of the opinion and the deliberation between justices as they write opinions. This is based on the assumption that longer opinions, on average, should contain more detailed explanation of the court’s opinion and will be the product of greater discussion and collaboration among the justices. Although we do not find that opinions are significantly longer or shorter on elected rather than appointed courts, our results hint at more subtle differences in the opinion-writing process based on the method of judicial selection a state employs.

Judicial selection and opinion length

Of all the institutional differences across state supreme courts, the method of judicial selection is easily the most discussed by researchers and observers alike. The various methods of selection are usually broken down into a few categories. Contestable elections allow for candidates to challenge sitting justices, either on a partisan or nonpartisan ballot, while retention elections ask voters only whether a named justice should be retained for another term in office. In contrast, several states allow the governor or legislature to select and retain justices without any type of election.

Previous research indicates that the method of selection is meaningful in several respects. Justices that face contestable elections are far more responsive to public opinion than their appointed counterparts. Elected trial court judges appear to behave similarly as they tend to impose harsher sentences, perhaps to avoid being attacked as “soft on crime” when seeking reelection. The effects of elections on the judiciary are thought to have intensified further in recent years as elections are more frequently contested with expensive, and largely negative, political campaigns.

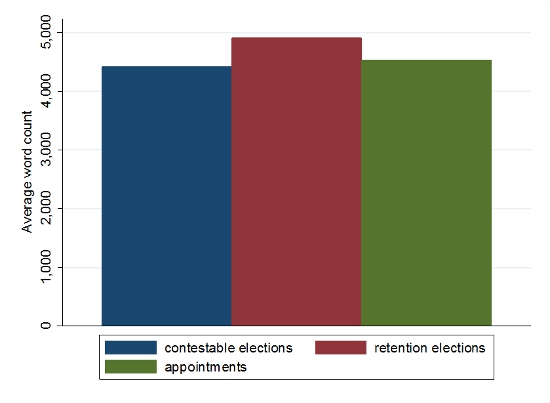

To determine whether there are differences in the length of opinions produced by elected and appointed justices, we collected data on all cases decided with a full opinion in the area of education by all state supreme courts from 1995 to 2005. Examining the average opinion length, measured as the word count for the majority opinion, reveals few differences based on the method of selection in the 1,186 cases included here. As illustrated in Figure 1 below, the average opinion ranges from 4,418 words in states with contestable elections to 4,910 words in states with retention elections.

Figure 1 – Average opinion length by method of judicial selection

Internal factors

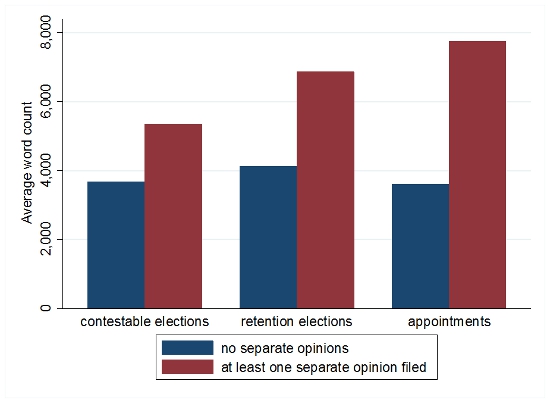

Though there are clearly no direct effects of method of selection on the length of a majority opinion, we contend that appointed and elected justices respond to different influences while writing opinions. Justices should be responsive to their colleagues while writing opinions, so we expected to see longer majority opinions in cases where another justice filed a separate concurring or dissenting opinion. This is generally true, though the magnitude of the effect of separate opinions varies across the methods of selection, as illustrated below in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Average opinion length when separate opinions are filed, by method of judicial selection

As we can see from the figure, opinions are longer in all courts when a justice files a separate opinion. This effect is magnified for courts where justices face only retention elections or appointments, however; on an appointed court, the average word count increases by over 4,000 words when at least one separate opinion is filed, while the increase is a more modest 1,677 words in courts with contestable elections. This suggests that appointed justices are more responsive to their colleagues when writing opinions than elected justices are, resulting in longer opinions, perhaps with more thorough justifications for the court’s reasoning.

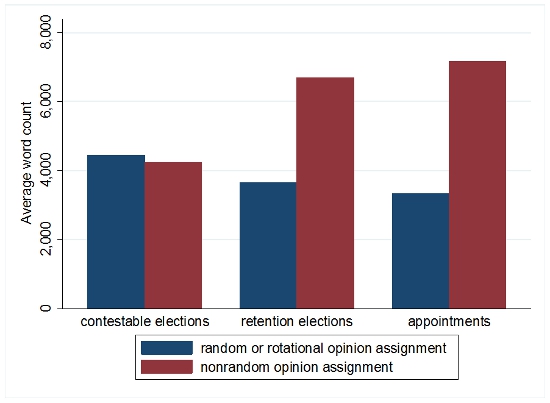

Another factor we expected to influence the length of an opinion is the method for selecting the author of the majority opinion. The majority opinion author plays a central role in the opinion-writing process as she is responsible for crafting the language that will eventually become precedent and has the greatest influence over the final policy output for a given decision. While some states follow the U.S. Supreme Court in allowing the chief justice or most senior justice in the majority to assign the majority opinion author, two-thirds of the state courts employed a random or rotational assignment procedure.

Although a random rotation may result in a fairer distribution of opinions by depoliticizing the process, a nonrandom opinion assignment rule allows an individual to assign each opinion to the justice most capable of writing the opinion, due to either their workload or a special interest or expertise in a certain area of law. Following this logic, opinions from courts with a nonrandom opinion assignment rule should be longer than those where opinions are assigned randomly. We can see in Figure 3 below that the opinion assignment rule has exactly the effects we would expect, but only in states where justices do not run in contestable elections. This result suggests that opinions may be assigned for different reasons in elected and appointed states, when a justice is given the power to do so.

Figure 3 – Average opinion length by opinion assignment rule and method of judicial selection

Considering the indirect effects of institutional rules

State supreme courts sit at the top of the judicial hierarchy in each state. As such, state supreme court justices are responsible for making decisions on some of the most important social and political issues of the day, including the death penalty, abortion, same sex marriage, and education funding. We know that elected justices tend to be more responsive to the public in making decisions, but our research indicates that there are also differences in how responsive an opinion author is to the other justices.

These results are surprising because writing an opinion is not a solitary exercise and not a purely academic one either. A chief justice with the power to assign the majority opinion author is expected to assign the responsibility to the justice with the expertise, interest, and time to write a high-quality opinion. In speaking for the court, a majority opinion author must be mindful of the preferences of the other justices in the majority and must consider their input, lest they lose their support and the majority. Yet, these results suggest that there may be substantial differences in the ways in which justices engage in the opinion-writing process and with each other based on the mechanism by which they may retain their positions.

This article is based on the paper ‘Understanding the Length of State Supreme Court Opinions’, in American Politics Research.

Image credit: Shawn Calhoun (CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1JYqklx

_________________________________

Meghan E. Leonard – Illinois State University

Meghan E. Leonard – Illinois State University

Meghan Leonard is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Politics and Government at Illinois State University. Her research focuses on state supreme court decision-making and the constraints on state supreme courts. Her work has appeared in State Politics and Policy Quarterly and the Justice System Journal.

Joseph V. Ross – Florida Gulf Coast University

Joseph V. Ross – Florida Gulf Coast University

Joseph V. Ross is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at Florida Gulf Coast University. His research deals with opinion-writing in state supreme courts and the effects of campaign finance restrictions in judicial elections.