Last week the Supreme Court ruled in favor of marriage equality across the entire United States, overturning bans in 14 states. The case was decided 5 votes to 4, with Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito dissenting under an Originalist or traditionalist interpretation of the Constitution. Leslie C. Griffin closely examines each of the dissents, writing that their arguments are not an honest interpretation of the Constitution, but an effort to prevent new groups and minority groups from enjoying the Constitution’s protection.

Last week the Supreme Court ruled in favor of marriage equality across the entire United States, overturning bans in 14 states. The case was decided 5 votes to 4, with Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Thomas, and Alito dissenting under an Originalist or traditionalist interpretation of the Constitution. Leslie C. Griffin closely examines each of the dissents, writing that their arguments are not an honest interpretation of the Constitution, but an effort to prevent new groups and minority groups from enjoying the Constitution’s protection.

Obergefell v. Hodges, Justice Anthony Kennedy’s landmark decision establishing marriage equality throughout the United States, confirms the importance of the Supreme Court’s interpreting the Constitution instead of imposing the interpretive theory of Originalism upon it. The four dissenters in the case—Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito–all wrote separate opinions. Each dissent demonstrated the empty formalism of Originalist or traditionalist interpretation, which tries to apply the Constitution as originally understood instead of interpreting it for the nation we live in today. Obergefell proves that Originalism cannot fulfill the Constitution’s promises of liberty and equality for all.

Justice Kennedy’s Opinion for the Court

In his opinion for the Court, Justice Kennedy (joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan) wrote that state bans on same-sex marriage violate the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Due Process Clause protects a fundamental right to marriage, and the Equal Protection Clause requires that heterosexual and same-sex marriages be treated equally.

The opinion exemplified four important features of authentic constitutional interpretation.

First, the Court understood that the brilliant Framers of the Constitution were not foolish enough to think they were drafting a document that both anticipated every future situation and determined how it should be resolved. Instead, the Court recognized that the Framers provided broad principles like due process and equal protection that need to be reinterpreted in every new era. Just as “[t]he history of marriage is one of both continuity and change” (slip op. at 6), so too is the history of constitutional interpretation.

Second, social developments and facts are relevant to constitutional interpretation, especially to the Court’s specific task to adjudicate cases and controversies. If we know today that homosexuality is not a psychiatric disorder, that it is not a choice but part of a person’s “immutable nature” (slip op. at 4), that LGBTQs are good parents, and that reproduction can occur artificially, then the Court cannot close its eyes to these developments. As “new dimensions of freedom become apparent to new generations” (slip op. at 7), the Court must respond to them.

Third, the “identification and protection of fundamental rights is an enduring part of the judicial duty to interpret the Constitution” (slip op. at 10). The courts exist to protect minorities against the oppression of majorities, not to defer (as the dissenters suggested) to democratic decisions that deny equal protection of the laws to disfavored groups.

Fourth, the Court is on solid ground when it expands the scope of constitutional rights to new groups traditionally discriminated against and disfavored in the political process, whether slaves, African Americans, women or LGBTQs. “If rights were defined by who exercised them in the past, then received practices could serve as their own continued justification and new groups could not invoke rights once denied” (slip op. at 18).

The dissenters rejected all those principles in favor of an empty Originalism or traditionalism, whose main purpose is to block traditionally disfavored groups from the liberty and equality enjoyed by the majority.

The Originalist Dissenters

Justice Scalia

Justice Scalia is the Father of Originalism, the simple and dangerous theory that limits constitutional protection to what it was when a constitutional provision was drafted. He applied it briefly in Obergefell:

When the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, every State limited marriage to one man and one woman, and no one doubted the constitutionality of doing so. That resolves these cases (slip op. at 4).

To read that reasoning is to reject it. On a strict theory of Originalism, racial segregation, women’s and LGBTQ inequality, and antimiscegenation laws would be with us for all time.

Justice Thomas

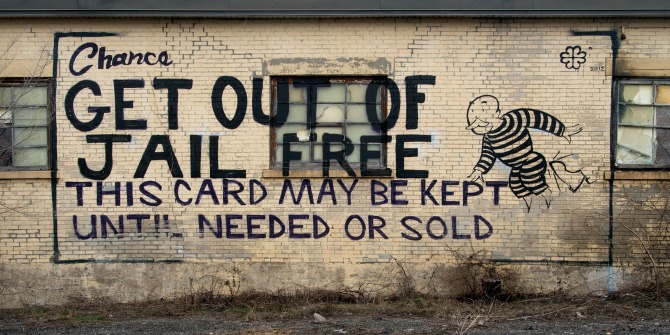

Justice Thomas’s Originalism is even more strict and esoteric than Scalia’s. With numerous references to Magna Carta and other historical texts, Thomas discerns—astonishingly–that the liberty identified in the Constitution protects “only freedom from physical restraint and imprisonment” by the government (slip op. at 13). Thus, under Thomas’s approach to the Constitution, contemporary Americans have lost almost all the liberties they take for granted in their daily lives.

Thomas makes the remarkable argument that LGBTQs have enough liberty today because they aren’t being physically restrained or imprisoned for participating in same-sex relationships, getting married or traveling around the country as couples. Remarkable because Thomas voted that LGBTQs could be imprisoned for sodomy when he dissented from Justice Kennedy’s opinion protecting same-sex relationships in Lawrence v. Texas.

Chief Justice Roberts

Chief Justice Roberts has never been an Originalist comparable to Scalia and Thomas, and sometimes he is pragmatic, as witnessed by his decisions upholding the Affordable Care Act in N.F.I.B. v. Sebelius and King v. Burwell. On marriage, however, he is a traditionalist who imposes outdated and constitutionally suspect traditions just as Originalists do.

Roberts thinks traditional marriage should stand until the democratic process overturns it. But this tradition is one of his own making. He repeatedly states that the “definition of marriage as the union of a man and a woman” is “universal,” “has persisted in every culture throughout human history,” for “all millennia,” across “all civilizations” (slip op. at 2), even though polygamy has been widely accepted across cultures and might even have been the norm through human history.

Roberts equates traditional marriage with the outdated Augustinian ideal that marriage must be procreative, even though American law has never required heterosexual couples to be fecund before granting them marriage licenses. In the closing line of his dissent, he concluded that the Constitution “had nothing to do with” same-sex marriage (slip op. at 29). That’s what happens when a Justice spends his time making up accounts of traditional marriage to impose on everyone instead of starting with the Constitution’s ideals of liberty and equality for all.

Justice Alito

In the past, Justice Alito has poked fun at Justice Scalia for his Originalism, observing drily in the violent video games case oral argument, e.g., “I think what Justice Scalia wants to know is what James Madison thought about video games.” In Obergefell, however, Alito, just like the Chief Justice, offers an impassioned defense of traditional marriage, repeating his dissent from United States v. Windsor that because traditional marriage is based on procreation (not love and companionship), states have the right to block nonprocreative LGBTQs from marriage equality. Of course, Alito’s point that “only an opposite-sex couple can … procreate” (slip op. at 4) ignores, as Originalism and traditionalism do, that modern reproductive technology has changed all that.

In an extraordinary and unprecedented defense of traditionalism, Alito goes even farther than Roberts. (They did not join each other’s dissents.) Alito thinks same-sex marriage can be denied to LGBTQs because, if marriage equality becomes legal, its opponents will be “vilif[ied],” “marginaliz[ed],” and “risk being labeled as bigots.” In other words, LGBTQs can’t enjoy the fundamental right to marriage because there is a block of people who don’t want them to enjoy their fundamental rights and don’t want to be criticized for saying so.

Alito’s extreme position confirms what Originalism and traditionalism are all about—not honest constitutional interpretation, but using the Constitution to thwart new groups and minority groups from enjoying the Constitution’s protection.

Responding to the dissenters’ historical fixation, Justice Kennedy insisted “History and tradition guide and discipline this inquiry but do not set its outer boundaries” (slip op. at 11). In other words, the majority correctly understood that the Constitution is much broader than the dissenters’ attempts to confine it to old ideas.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1BRDAXP

_________________________________

Leslie C. Griffin – University of Nevada

Leslie C. Griffin – University of Nevada

Leslie C. Griffin is the William S. Boyd Professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Boyd School of Law. She is author of Law and Religion: Cases and Materials as well as numerous articles and book chapters about constitutional law, law and religion, politics and ethics. She blogs about religious liberty at Hamilton and Griffin on Rights, www.hamilton-griffin.com.