Last month marked the 800th anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta, an agreement between King John of England and feudal Barons, which played a key part in establishing values we know today such as the right to a fair trial and equality under the law. Tim Oliver and Cora Lacatus look at the historical and continuing importance of Magna Carta for both Europe and the U.S., writing that its precedent has played a role in fuelling political change in the form of the American and French revolutions as well as the setting up of human rights conventions in the aftermath of the Second World War. In light of concerns over U.S. aggressive foreign policy and the increasing power of multinationals, they argue that the anniversary of Magna Carta provides a reminder of the ongoing struggle to uphold the rule of law on both sides of the Atlantic and around the world.

Last month marked the 800th anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta, an agreement between King John of England and feudal Barons, which played a key part in establishing values we know today such as the right to a fair trial and equality under the law. Tim Oliver and Cora Lacatus look at the historical and continuing importance of Magna Carta for both Europe and the U.S., writing that its precedent has played a role in fuelling political change in the form of the American and French revolutions as well as the setting up of human rights conventions in the aftermath of the Second World War. In light of concerns over U.S. aggressive foreign policy and the increasing power of multinationals, they argue that the anniversary of Magna Carta provides a reminder of the ongoing struggle to uphold the rule of law on both sides of the Atlantic and around the world.

The recent 800th anniversary celebrations of the signing of Magna Carta served as a reminder of the historical links binding England and the United States. Magna Carta reflects ideas that were sweeping across medieval Europe, ideas that later crossed the Atlantic and which today form part of the strong links between the two sides of the North Atlantic.

The document which a group of 25 rebellious francophone barons forced the reluctant Anglo-Norman King John to sign at Runneymede in 1215 had more to do with feudal rights than some of the myths now associated with it. Nevertheless, Magna Carta – myths and all – has played a key part in establishing universal values we take for granted, namely that everybody should be equal before the law, that no ruler is above the law, and that all should receive a fair trial.

The question remains, however, whether either side of the Atlantic should boast about the importance they attach to Magna Carta. One only has to think of Guantanamo Bay or challenges to the European Convention on Human Rights to see that upholding the rule of law remains a challenge for both parties. And in other parts of the world, these ideals struggle to find their voice.

A document for the English-speaking world?

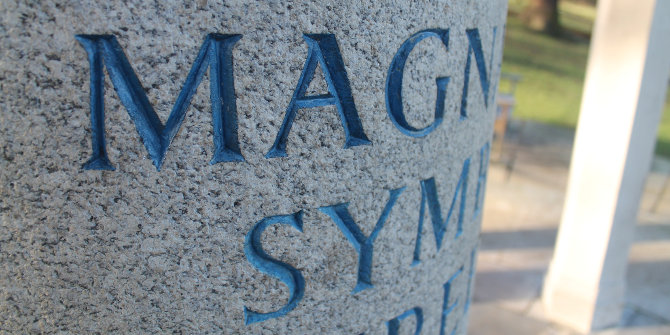

If any country looks to Magna Carta as a document for inspiration it is the United States. England’s lack of a codified constitution or bill of rights means that while Magna Carta is celebrated, it is not as venerated as it is in the USA. Visit the US National Archives and before you see the Declaration of Independence, Constitution or Bill of Rights, you’ll see a 1297 copy of Magna Carta. Its signing is beautifully depicted on the golden doors of the US Supreme Court. Visit Runnymede and you see it is the American Bar Association that has contributed so much to the memorials marking the location. No wonder then that Magna Carta and the common law system connecting the USA, UK and many other English speaking countries has led to claims that the ideas of liberty and rule of law owe their existence to the English speaking peoples.

A Transatlantic Document

To credit the English speaking peoples with such a creation would be to overlook how European Magna Carta is and how universal its values are. Its signing was without a doubt a key moment, but similar charters were emerging across Europe both before and after 1215. These were based around guilds, communes, and were in no small part the product of the spread of trade around Europe giving rise to the need for freedom and stability in the interpretation and enforcement of the rule of law.

What then we all owe to Magna Carta is a moment in England’s history to which philosophers around Europe, political movements such as the Levellers, or the Founding Fathers of the USA could look back to as an important precedent for an on-going struggle to enforce the rule of law and liberty. As such, it has played a leading role in a powerful narrative that has fuelled political change in Britain, North America, and Europe, in particular the American and French revolutions.

In time that narrative has helped create documents drawn up by both sides of the North Atlantic: for instance, the 1941 Atlantic Charter, the 1948 United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, and the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights. Born from the hell of the Second World War, when the rule of law disappeared from much of Europe, they have all taken – or tried to take – accountability to the next level by making clear that states are also beholden to the rule of law in their actions. The end of the Cold War saw countries across Eastern Europe embrace these ideals to bring them into the mainstream of European and transatlantic democracies. It is befitting then that UNESCO has included Magna Carta in the Memory of the World Register, noting that, ‘It has become an icon for freedom and democracy throughout the world.’

Transatlantic Failings

This all sounds very grand and encouraging. But can the UK, Europe or the USA boast about Magna Carta given their own failings when it comes to enforcing the rule of law? The USA’s own failings are more than well enough documented. Most will think immediately of Guantanamo Bay where hundreds of men have been detained without trial for over a decade with no resolution in sight. The list goes on to include rendition, spying, targeted killings, to say nothing of domestic problems surrounding race and the USA’s judicial and law enforcement systems.

Europe itself should be careful not to think it can boast too much. European governments have resorted to detention without trial. Unease at the state of various judicial systems around Europe has made for uncomfortable cases where the EU’s European arrest warrant was enforced. Austerity has meant cuts to financial support for legal cases, meaning the rich stand a better chance of securing a fair trial than the poor. Opposition to the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership is often based on fears that multinational companies will be able to bypass national laws, allowing them to enjoy privileged rights that are above the rule of law. The European Union itself can appear a distant, unrepresentative system of law making.

The international politics of Magna Carta

Magna Carta has also become embroiled in some of the international agendas advanced by the US and European governments. Spearheaded by Europe and the US, the idea of spreading the rule of law and democracy around the world has long been present. It played an important role during the Cold War and since the events of the September the 11th, 2001 has become a central justification of Western foreign policy. The failures of approaches taken since 9/11 and the failings of the West itself to live up to some of the ideals we associate with Magna Carta threaten to weaken the spread and legitimacy of such ideals rather than advance them.

If there is a powerful lesson about Magna Carta and its role in the advancement of liberty and the rule of law, it lies in providing a moment in history to which people on either side of the North Atlantic can look back to as one of the most important precedents for checking rulers and enforcing the rule of law. Similar examples can be found in the histories of Russia, China, Islam, and throughout the rest of the world. Sometimes, however, they are deliberately forgotten and hidden from view by political systems that fear people using such historical examples to challenge their current rulers. Remembering and celebrating Magna Carta should serve then as a reminder of not only the ongoing struggle to uphold the rule of law in England, the USA or Europe. It should serve as a reminder of a struggle found throughout the world.

The research for this blog was supported by the Dahrendorf Forum, a joint initiative by the Hertie School of Governance, LSE and Stiftung Mercator. A version of this article originally appeared at the blog of the Dahrendorf Forum blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1go9DF8

_________________________________

Tim Oliver – LSE IDEAS

Tim Oliver – LSE IDEAS

Tim Oliver is a Dahrendorf Postdoctoral Fellow on Europe-North American relations at LSE IDEAS.

_

Cora Lacatus – LSE International Relations

Cora Lacatus – LSE International Relations

Cora Lacatus is the LSE Research Associate on the Dahrendorf Europe-North American Working Group and on the MAXCAP Project.

1 Comments