A common explanation for continued economic hardship and unemployment in many cities in the U.S. is workers’ lack of ability or desire to move. In new research which examines more than 722 ‘commuting zones’, Michael Amior and Alan Manning find that many cities which have endured declining employment have also experienced large population outflows, but because of continued industrial decline, there has been little change in the local employment rate. They argue that while firms might be attracted by these cities’ low wages and slack labor markets, these advantages are ultimately undone by the large migratory outflows, which reduce the supply of labor and demand for local services.

A common explanation for continued economic hardship and unemployment in many cities in the U.S. is workers’ lack of ability or desire to move. In new research which examines more than 722 ‘commuting zones’, Michael Amior and Alan Manning find that many cities which have endured declining employment have also experienced large population outflows, but because of continued industrial decline, there has been little change in the local employment rate. They argue that while firms might be attracted by these cities’ low wages and slack labor markets, these advantages are ultimately undone by the large migratory outflows, which reduce the supply of labor and demand for local services.

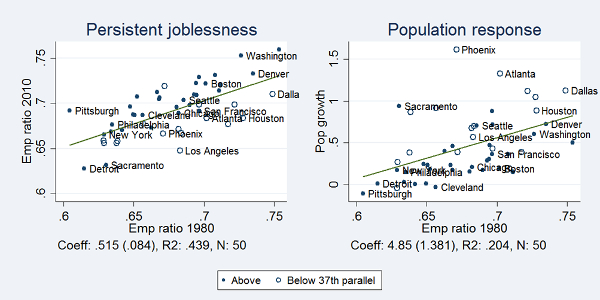

Back in the 1970s, Detroit was a by-word for economic misery, and that is still the case today. Indeed, across commuting zones (CZs) in the U.S., differences in joblessness have persisted for many decades. The first panel of Figure 1 shows that a CZ’s employment-population ratio (among individuals aged 16-64) in 1980 is an excellent predictor for the employment-population ratio today.

Figure 1 – Persistence in employment ratio and population response

In a recent study with Alan Manning, we have found that this persistence cannot be explained by local differences in demographic composition (whether education or ethnicity), the propensity of women to work, or the presence of natural amenities. Rather, it reflects real differences in the economic opportunities facing the same types of people.

Many commentators have blamed a lack of geographical mobility. Following a contraction of the local economy, it is claimed, people have simply failed to leave – and this explains why joblessness has remained stubbornly high. But, the second panel of Figure 1 reveals a large migratory response to initial jobless rates. The population of Detroit, in particular, has stagnated since 1980; and Cleveland and Pittsburgh have actually shrunk. In contrast, those cities with the best initial conditions have almost doubled in size – even if the unusually large growth in Sunbelt cities (identified in the figure by the open markers) is discounted.

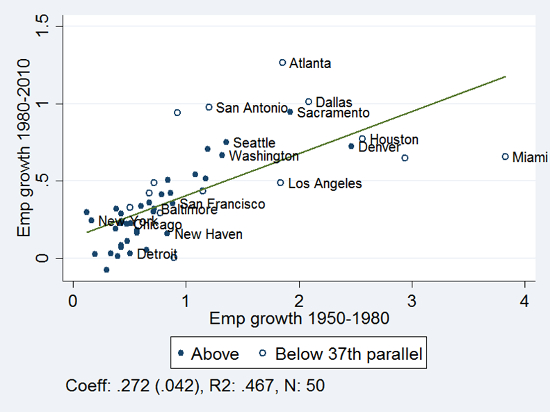

We argue the missing piece of the puzzle is the persistent contraction of local industries. As Figure 2 shows, employment growth between 1950 and 1980 is strongly correlated with growth between 1980 and 2010. Those cities which shed manufacturing jobs in the 1970s continue to shed them today. While local population has responded strongly, it has never caught up with employment. And consequently, against a backdrop of rapidly changing employment and population, the gap between the two (that is, the local employment rate) has remained remarkably persistent.

Figure 2 – Persistence in local employment growth

Based on decadal census data going back to 1950 and covering 722 CZs, we have attempted to estimate the size of the local population response. We find that a CZ suffering an employment-population ratio 10 percent lower than the national average can expect to lose almost 5 percent of its local population over one decade. So within two decades, all else equal, the employment ratio should have returned to the national average. In practice, this does not happen; and this is a consequence of a persistent contraction of employment.

Until now, in this article, I have focused only on migration as a means of adjustment of local labor markets. Of course, adjustment can materialize in other ways. First, firms may be attracted to cities like Detroit because of a slack labor market and low wages. But, these advantages are undone by the large migratory outflows, which reduce the supply of labor and demand for local services. So overall, these employment responses do little to reduce local jobless rates.

Second, “commuting zones” (as commonly defined in the academic literature) are not isolated labor markets. Despite their name, workers do commute between them, and these long-distance commuting flows have grown over time. We find that some workers respond to local joblessness by commuting out of their CZ, and this may account for about a quarter of the overall adjustment of local employment rates (with the remainder due to migration).

To summarize, we find that the persistence of local joblessness is largely due to persistent contractions of employment, rather than the immobility of labor. Indeed, we have identified large migratory responses to local employment conditions. This suggests that local joblessness needs to be addressed by diversifying the industrial base, rather than encouraging out-migration. Seattle, for example, invested successfully in new technologies in recent decades. But in general, this is easier said than done. As Figure 2 shows, few cities with weak historic jobs growth have picked up markedly; and the exceptions are mostly Sunbelt cities, which may have simply benefited from natural advantages such as plentiful land.

This article is based on the LSE CEP Discussion Paper ‘The Persistence of Local Joblessness’.

Featured image credit: Bart Everson (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1SmRcfS

______________________

Michael Amior – LSE Centre for Economic Performance

Michael Amior – LSE Centre for Economic Performance

Michael Amior is a Research Officer at the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE. His research interests include Labour, Migration, Education, Housing, and Urban Economics.

Alan Manning – LSE Economics

Alan Manning – LSE Economics

Alan Manning is professor of economics at LSE and director of the communities programme in the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE.

I am not sure if the US situation is the same as the UK but I think there is one aspect of the story that you might need to discuss before your conclusions can be considered definitive.

In the UK (until relatively recently) the great cities of the UK – including London – had been losing (industrial) jobs and population in much the same way that you describe Detroit and other US cities. Some of this is described in work by Ivan Turok and we also discussed it in the Government publications of the mid 2000s – Full Employment in Every Region. I can also send you an RSA presentation which is primarily about London.

This issue that I’d like to mention is that despite the fact that there had been job and population losses in cities they still remain the places where jobs are concentrated. It is just that many of the jobs are taken by commuters. A more recent description of this phenomenon is set out in a presentation that I gave at a seminar on the 40th anniversary of the LFS (below).

http://www.slideshare.net/statisticsONS/using-the-lfs-man-and-boy

Given that ‘The streets of London are not paved with gold for Londoners’ I still think there is an issue about why employment rates are not higher in cities.

Happy to discuss.