As has been the case in the U.S., the level of inequality in Canada has been on the rise since the 1980s, though at a slower rate. In new research, Barry Eidlin explores the reasons behind this divergence. He argues that one major factor which has received little attention is the power of Canada’s unions. He writes that because unions have been able to keep their role and legitimacy as defenders of working class interests, they have largely retained their power. He argues that in order to address inequality, we need to talk more about the growing divide between the wealthy and the working class, and the role that unions can play in decreasing that divide.

As has been the case in the U.S., the level of inequality in Canada has been on the rise since the 1980s, though at a slower rate. In new research, Barry Eidlin explores the reasons behind this divergence. He argues that one major factor which has received little attention is the power of Canada’s unions. He writes that because unions have been able to keep their role and legitimacy as defenders of working class interests, they have largely retained their power. He argues that in order to address inequality, we need to talk more about the growing divide between the wealthy and the working class, and the role that unions can play in decreasing that divide.

While Canada is generally known abroad for its exports (movie stars and musicians to the U.S., central bank governors to the UK), what goes on inside its borders tends to attract less attention. This is unfortunate, as the country primarily recognized as the United States’ “friendly neighbor to the North” offers important insights into some of the central problems preoccupying scholars, activists, and organizations concerned with power and social policy.

Take the problem of income inequality, which has garnered increased attention in recent years thanks to the activism of Occupy and the Eurocrisis, along with the scholarship of Thomas Piketty and his collaborators. While growing inequality is a problem across the industrialized world, it is not having the same effects everywhere. Understanding where the differences come from can help develop strategies for addressing inequality.

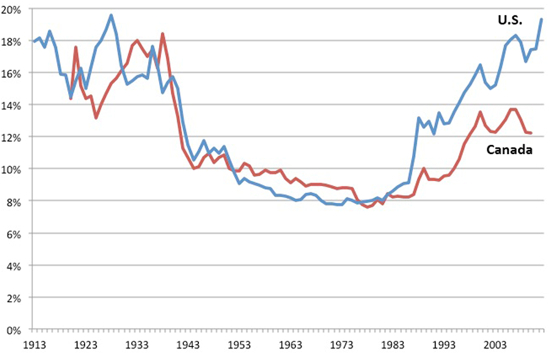

For example, the U.S. is famously the poster child for growing inequality. As of 2013, the top one percent of Americans were capturing 17.5 percent of total income, a level not seen since the early 20th century. But what about Canada? Unsurprisingly, given its socio-economic similarity to the U.S., inequality is also on the rise up north. But a look at the historical data shows an interesting pattern:

Figure 1 – Top 1% of Income Share, U.S. and Canada, 1913-2012

Source: World Top Incomes Database

Starting in the 1980s, we see a divergence. Inequality grew in Canada, but not as much as in the U.S. What’s behind this divergence? There are many factors, of course, but my research suggests an important one that hasn’t gotten much attention: differences in labour union strength. In a world where the wealthy have an outsized say in politics and public policy, unions are among the only organizations that are designed with the explicit purpose of balancing the scales.

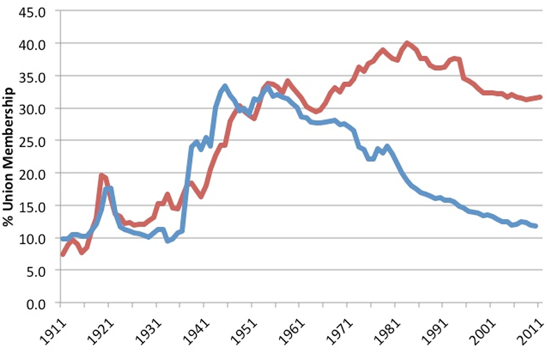

We know from existing research that U.S. union decline was a key driver of the growth in inequality there. What happened in Canada? As we see in the graph below, unionization rates were very similar up until the mid-1960s, then diverged.

Figure 2 – Union Density, U.S. and Canada, 1911-2011

Source: Barry Eidlin, “Class vs. Special Interest,” Appendix B

Today, Canadian unionization rates are nearly three times higher than in the U.S. And while unions have declined since their peak in the early 1980s, Canada is one of the only industrialized countries where current unionization rates remain similar to what they were in the early 1970s.

“Class” vs. “Special Interest”

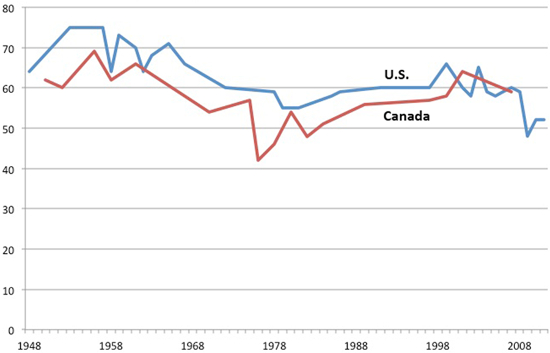

Why have Canadian unions done better than their U.S. counterparts? Some might argue that it’s because Canadians are more sympathetic to unions, or because Canadian labour laws are stronger than in the U.S. But Gallup polling data shows little difference between Canadian and U.S. attitudes towards unions. And while current labour laws are indeed stronger in Canada than in the U.S., that was not always the case. Canadian labour law was considered worse than U.S. law prior to the divergence, and many of the pro-labor legal reforms in Canada were implemented a decade or more after U.S. and Canadian unionization rates began to diverge.

Figure 3 – Percentage who Approve of Unions, U.S. and Canada, 1948-2011

Source: Gallup polls.

In a recent article and forthcoming book, I put forth a new theory: Canadian unions remained stronger because they were better able to retain a legitimate social and political role as defenders of working class interests. By contrast, U.S. unions got painted as a narrow “special interest.”

These different roles for labour weren’t just rhetorical. They were built into how unions are viewed by the legal system and political parties, and even how unions viewed themselves. While U.S. unions’ “special interest” role de-legitimized class issues, eroded workers’ legal protections, and constrained labour’s ability to act, Canadian unions’ “class representative” role gave class issues greater legitimacy, strengthened legal protections, and imposed fewer constraints on labour.

It’s important to stress that Canadian unions didn’t adopt this “class representative” role because they were more radical than their U.S. counterparts, and Canadian labour law didn’t stay stronger because of more sympathetic governments. Rather, it was the result of a labor policy designed first and foremost to keep labour unrest in check. For example, while unions’ ability to strike was restricted, so too was employers’ ability to replace strikers or interfere in union certification campaigns.

The dynamic that this policy framework created reinforced for labour the importance of mobilizing to win demands, as opposed to finding sympathetic political allies from whom to seek favorable treatment. For employers and government officials, it reinforced the importance of a strong labour policy to discipline unions.

Lessons for Today

What broader lessons can we draw from this comparison of U.S. and Canadian unions? The key point is that if we want to do something about runaway income inequality, we need to address the power inequality that underlies it.

At a policy level, that means laws that level the playing field for labour. But more broadly, it means that we need to talk about the working class. Politicians, union officials, and other civic leaders talk far too much about a mushy – and somewhat meaningless and outdated – “middle class.” They need to acknowledge the real and growing class divide between the wealthy and the working class.

While Canadian labour laws still help address the power imbalance between workers and employers, the space for frank discussions of class is narrowing. Even organizations that defend working class interests, like the labour-backed New Democratic Party and the Canadian Labour Congress union federation, shy away from mentioning the working class in favour of vague defenses of the “middle class.” At the same time, even though union strength hasn’t declined nearly as much as in the U.S., Canadian unions currently face serious challenges of their own.

Of course, this is not solely a Canadian phenomenon. Across the industrialized world, class rhetoric has declined considerably, even as class divides have increased. But that is precisely why the Canadian case is important: it’s symptomatic of a broader problem.

The problem has no easy solutions, but addressing it starts with an accurate diagnosis. By recognizing the power inequality underlying income inequality, bringing class and unions back into the discussion of inequality is a good place to start.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Class vs. Special Interest: Labor, Power, and Politics in the United States and Canada in the Twentieth Century’, in Politics & Society.

Featured image credit: United Steelworkers (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0).

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1RPqBNw

_________________________________

Barry Eidlin – McGill University

Barry Eidlin – McGill University

Barry Eidlin is an assistant professor of sociology at McGill University and an affiliate of the Scholars Strategy Network.