Political scientists have been trying to understand how political campaigns affect voter turnout for decades. Now, with the rise and ubiquity of social media platforms such as Facebook, those who study political campaigns have access to a new and potentially vast data source on voters’ intentions. In new research, Jaime Settle analyses over 100 million Facebook updates, finding that 1.3 percent more users in battleground states posted status updates about politics, and that this increased their likelihood of voting by nearly 40 percent.

Political scientists have been trying to understand how political campaigns affect voter turnout for decades. Now, with the rise and ubiquity of social media platforms such as Facebook, those who study political campaigns have access to a new and potentially vast data source on voters’ intentions. In new research, Jaime Settle analyses over 100 million Facebook updates, finding that 1.3 percent more users in battleground states posted status updates about politics, and that this increased their likelihood of voting by nearly 40 percent.

Ask any practitioner of campaign politics in the United States and she will tell you that campaigning matters. Yet for decades, political scientists have had great difficulty demonstrating that campaigning actually causes people to change their minds or cast a vote. The growth of field experiments in political science and the heightened awareness among elite campaign staffers of the value of experiments have ameliorated this situation somewhat. We know more now than ever about how the tactics used in competitive elections—the television ads, phone calls, mailers, and door knocks that are the hallmark of 21st century American politicking—affect political behavior.

Yet, both practitioners and political scientists have largely focused on the very last behavior that occurs in an election season: casting a vote. Ultimately, whether and for whom someone votes should remain at the center of our collective attention, but without understanding all the small changes in attitudes that connect campaign exposure to the voting booth, we will not be able to further refine our mobilization and persuasion techniques.

Researchers implicitly assume that the effects of political competition on voter turnout must be mediated through smaller and more proximate changes in attitudes and behavior, but this assumption has rarely been explicitly tested. In recent research, my colleagues and I attempt to do just that. We focus on an everyday behavior that is now one of the most ubiquitous activities in the lives of many Americans: posting a status update on Facebook.

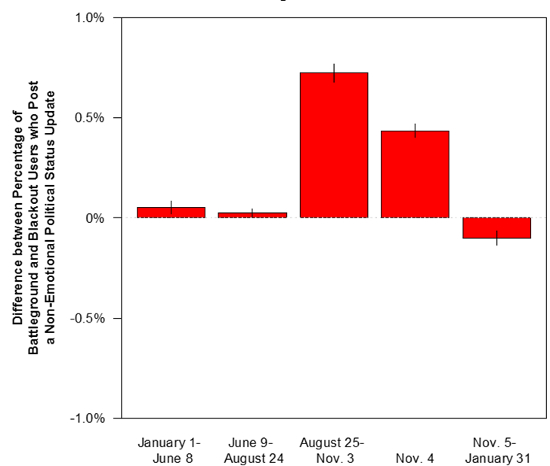

In strict adherence with Facebook’s data use policies, we utilize a unique data source—over 100 million status updates posted by two million American adults—to suss out how it is that competition changes people’s day-to-day behavior in a way that results in an increased likelihood that they report voting. We show that 1.37 percent more users living in battleground states post a Facebook status update about politics compared to the percent of blackout users who do. Figure 1 below shows that this happens mostly in the weeks leading up to Election Day and on Election Day itself. We also show that posting a political status update increases the probability of self-reported voting on Election Day by almost 40 percent.

Figure 1 – Difference in percent of political users, Battleground vs. Blackout

The effect of battleground status on users’ political status update posting. The figure shows the differences between the percent of users making a political post in the battleground states as compared with the blackout states, during five different time periods of the 2008 campaign.

Our research is important for two reasons. First, our results help us understand something about the American political experience that has historically been incredibly difficult to measure: minute changes in people’s daily behavior. This is one of the first examples of a “big data” social media study testing hypotheses derived from the political behavior literature. As we write in the paper, new techniques rooted in computational social science can be applied to new data sources to “offer the possibility of moving beyond snapshots to a minute-by-minute motion picture of the dynamic political engagement of the American public. Scholars interested in studying how people behave politically can come closer to realizing the long-desired goal of characterizing that behavior as it happens—while it happens—in the real world. For the first time, we can capture what people are thinking and talking about with regard to politics as those opinions and conversations are formed.”

Social media data allow us to capture novel behaviors, like status update posting, that may not necessarily entail high levels of interest in or knowledge about the campaign or politics, yet appear to affect voting behavior. Although we imagine that on average, people who post political status updates are more interested in politics, the behavior is conceptually distinct from campaign interest. A person who posts, “I am so tired of all of these campaign commercials and wish that they would stop” would be coded in our study as having posted a political status update, but this person may not be likely to report on a survey that he is interested in the campaign or may not be able to report anything substantive about the candidates.

Furthermore, analyzing social media data is important because it complements and extends the more traditional approaches social scientists have used to gather data. The large scale of social media data—creating the possibility of studying everyone who engages in a behavior, not just small, albeit representative, samples— makes it much easier to tease out complex relationships between different variables. Additionally, collecting unobtrusive data measuring people’s political behaviors help researchers avoid some of the problems that can make it hard to interpret research using self-report measures alone. For example, prior survey research has show that people living in a battleground state are more politically interested and informed. These studies offer suggestive evidence that political competition causes higher levels of political engagement. But this prior work cannot rule out an equally probable alternate explanation: the fact that one of the effects of living in a battleground state might be to change people’s perceptions that they should care about politics. Consequently, the higher levels of reported interest may reflect the desire of some individuals to appear as if they care about politics because those around them do, an example of what researchers call social desirability bias, as much as an actual change in behavior.

We suggest that utilizing social media data in theoretically informed ways can meaningfully advance what we know about political behavior. Others have noted the dangers of using social media data as simply a measure of public opinion, identifying both methodological and theoretical reasons to have concern about the inference of these findings. Despite these concerns, we can and should responsibly use data from social media sites to build on what we think we know about political behavior more broadly, empirically testing ideas where before we could only speculate. A handful of other academic researchers, often in partnership with corporate data scientists, have helped us better understand phenomena like the tendency to be friends with people who have similar political beliefs, how people choose which political news to read, and social influences on voter turnout.

As with much academic research, our results raise as many questions as we answer. For example, how is status update posting similar to, and different from, its offline cousins, political discussion and seeking out political news? We suggest that posting “is a low-cost expressive behavior that can be easily accomplished by both the politically sophisticated and unsophisticated, by partisans and non-partisans, by those with resources and those without.” But this characterization begs for more exploration. In other work, I argue that we should consider more seriously what it is people are doing when they post or read political material on Facebook, and what the consequences of that communication are not only on opinions about policy but also on our opinions of each other. Continued study is important to further our understanding of the influences affecting our political decision-making processes, behaviors and attitudes.

This article is based on the paper, ‘From Posting to Voting: The Effects of Political Competition on Online Political Engagement’ in Political Science Research and Methods.

Featured image credit: kropekk_pl (Pixabay, Public Domain)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1PCflP3

_________________________________

Jaime Settle – College of William & Mary

Jaime Settle – College of William & Mary

Jaime Settle is an Assistant Professor of Government at the College of William & Mary, where she directs the Social Networks and Political Psychology Lab and co-directs the Social Science Research Methods Center. Her work focuses on how political contexts and social interactions affect our political behavior, and how innate differences between people (genetic, physiological, and psychological differences) moderate the effects of those contextual and interpersonal exposures.