Presidential candidates put vast amounts of money and resources into lengthy campaigns. But to what extent are voters influenced by these campaigns? Using new research, Peter Enns argues that the fundamentals, such as economic conditions and incumbent approval ratings, are the most important determinants of voters’ choices. He finds that voters’ interest in elections has more to do with relying on these fundamentals than knowledge about the candidates or attention paid to the campaign.

Presidential candidates put vast amounts of money and resources into lengthy campaigns. But to what extent are voters influenced by these campaigns? Using new research, Peter Enns argues that the fundamentals, such as economic conditions and incumbent approval ratings, are the most important determinants of voters’ choices. He finds that voters’ interest in elections has more to do with relying on these fundamentals than knowledge about the candidates or attention paid to the campaign.

The horse race polls for 2016 have already begun (e.g., here and here). But if you want to know which candidate is going to win the next U.S. presidential election, political scientists (and some late night comedy hosts) admonish us not to look at who is ahead in the early polls. The fundamentals, such as economic conditions and the approval levels of the incumbent have a much more impressive track record predicting election outcomes.

Perhaps ironically, the fact that the early polls make poor bellwethers of election outcomes has greatly informed political scientists’ understanding of campaign effects. Scholars view the contrast between the predictability of presidential elections and the variability of the early polls as evidence that campaigns provide crucial information to voters. This information enables voters to select the candidate that best corresponds with the fundamentals, such as economic conditions, presidential approval, partisanship, and demographic interests. Indeed, as the campaign unfolds, and more and more information is provided to the electorate, survey respondents increasingly base their vote intentions on these fundamentals.

But what if voters don’t need an entire campaign to connect the fundamentals to their vote choice? After all, it doesn’t take much political knowledge to connect one’s partisanship, approval of the president, or even economic evaluations to either the Democratic or Republican candidate. Brian Richman and I, have a new explanation for why vote intentions in early polls correspond less with these fundamentals.

We propose that for much of the campaign, Election Day feels distant. The actual vote is an abstract, almost hypothetical decision. When talking on the phone to a pollster, many respondents don’t think about their vote the same way they would if they walked into a voting booth. Instead of reflecting on the fundamentals, such as the state of the economy, these respondents rely on the most accessible information—perhaps supporting (or opposing) a candidate based on a recent headline, advertisement, or scandal. Critically, most respondents could connect the fundamentals to their voting intentions; they just don’t have an incentive to do so. Thus, we propose that the motivation to engage with the survey question, not information from the campaign, is the primary reason reliance on the fundamentals increases as the election nears.

To test this prediction, we utilized the 2000 National Annenberg Election Survey: a national survey conducted each day of the presidential campaign. To identify whether respondents were motivated to think about the vote intention question like an actual vote choice, we looked at whether or not respondents “cared a good deal which party wins the presidential election.” Those who cared about the election outcome should have been more motivated to treat the survey question like an actual vote choice and to offer an optimal survey response.

To identify whether respondents relied on the fundamentals, we first examined the relationship between the fundamentals and vote choice (Bush or Gore) during the final week of the campaign. These relationships from the end of the campaign served as the “correct” or “fully informed” fundamental weights; i.e. to what extent did these fundamental variables inform the actual voting decision. For each survey from the entire campaign, we then identified whether respondents’ vote intentions (Bush or Gore) matched what we would predict if they had relied on these end of campaign “correct” fundamentals. The key question was, after controlling for information provided by the campaign, were respondents who cared more about the election outcome more likely to express a vote intention that matched the fundamentals?

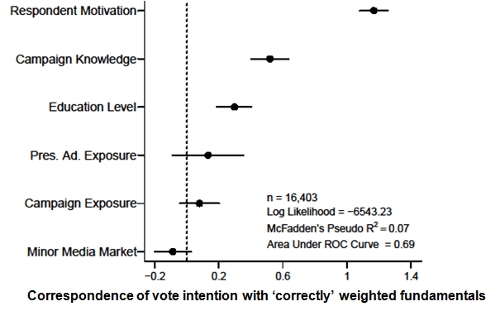

The results of this analysis, shown in Figure 1, indicated that knowing whether or not respondents cared about the election outcome (Respondent Motivation) was a more important predictor of whether their vote intention corresponded with the fundamentals than any of the measures of campaign information. Caring about the election appears to have a lot more to do with relying on the fundamentals than knowledge about the candidates or attention paid to the campaign.

Figure 1 – Relationship between Respondent Motivation (caring about the election) and Vote Intentions in 2000 Presidential Campaign.

Note: Horizontal lines reflect 95% confidence intervals. To facilitate the comparison of coefficients, non-binary variables have been standardized to a standard deviation of 0.5.

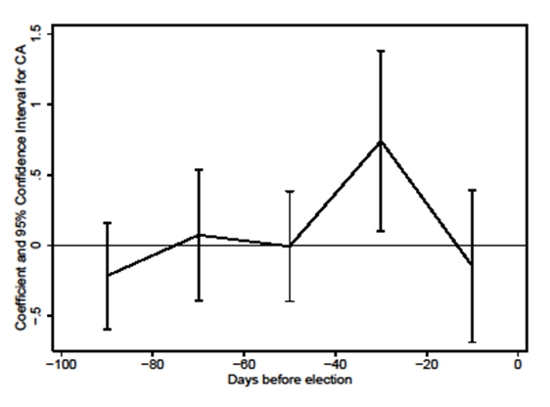

Of course, if it is the engagement with the survey question that matters, making the election (and thus the vote choice) salient should increase reliance on the fundamentals—even if no new information becomes available. A unique feature of California’s election laws allowed us to test this hypothesis. Between 40 and 21 days prior the election, all registered voters in California receive a voter guide. In 2000, this 84 page guide offered a concrete reminder of the upcoming vote choice. Furthermore, because the guide focused on California’s ballot initiatives, it provided almost no information about the presidential candidates. Thus, during a two-and-a-half week period, registered voters in California received a salient reminder of the upcoming presidential election without receiving any additional information about the candidates. Figure 2 shows that during this period (and only this period), registered voters in California were more likely than registered voters in other states (controlling for all of the campaign information measures analyzed above) to link their vote intentions to the fundamentals. It appears that even without additional information, when reminded of the upcoming vote choice; Californians were more likely to link the fundamentals to their surveyed vote intention.

Figure 2- Estimated Effect of California Voter Guide on Expressing a Vote Intention that reflects the “Correctly” Weighted Fundamentals.

Note: The figure reports the estimated relationship (and 95% confidence interval) between being a registered voter in California (relative to being a registered voter in another state) and expressing a vote intention that corresponds with the “correctly” weighted fundamentals. The period -40 to -20 corresponds with the dates that California mails the Voter Information Guide.

The fundamentals matter in U.S. presidential elections. Importantly, our results suggest that the campaign plays a much smaller role with these fundamentals than previously thought. This conclusion does not, however, mean that campaigns don’t matter. In a close election, even a minor campaign event can influence the outcome. Irrelevant considerations, such us football victories and shark attacks, can also influence election outcomes. Putting this all together, when looking ahead to 2016, we don’t need to wonder if the campaign will get voters to rely on the fundamentals—most can (and will) do this on their own. The real question is whether the campaign (or other events) will get voters to deviate from the fundamentals.

This post is based on a recent article, Presidential Campaigns and the Fundamentals Reconsidered, in the Journal of Politics.

Featured image credit: DonkeyHotey (Creative Commons BY)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1dPhuZs

_________________________________________

Peter K. Enns – Cornell University

Peter K. Enns – Cornell University

Peter Enns is Assistant Professor in the Department of Government at Cornell University. His research and teaching interests focus on public opinion, representation, and quantitative research methods. In particular, he is interested in whose policy preferences change, why, and whether government responds to these changes. He is also co-editor of the book, Who Gets Represented? (Russell Sage Foundation, 2011).

I think that this might be the most incredible thing I’ve read in a long time. Excellent excellent research. Top notch stuff.