Polarization has become an inescapable feature of US politics on issues from abortion rights to defense and foreign policy, and in recent decades, environmental politics has not been exempted from this trend. In Congress, the polarization of environmental politics has been rising and strong, with Democrats now tending to support pro-environmental (“green”) legislation and Republicans opposing it. In new research, Dean Lueck, Julio A. Ramos Pastrana, and Gustavo Torrens find that party affiliation not only affects voting on environmental issues among otherwise similar politicians and constituents, but it also affects interest groups’ contributions to politicians.

Polarization has become an inescapable feature of US politics on issues from abortion rights to defense and foreign policy, and in recent decades, environmental politics has not been exempted from this trend. In Congress, the polarization of environmental politics has been rising and strong, with Democrats now tending to support pro-environmental (“green”) legislation and Republicans opposing it. In new research, Dean Lueck, Julio A. Ramos Pastrana, and Gustavo Torrens find that party affiliation not only affects voting on environmental issues among otherwise similar politicians and constituents, but it also affects interest groups’ contributions to politicians.

Polarization in the US Congress has a varied history. In recent years polarization has been present on reproductive rights, gun control and environmental legislation. Environmental issues have been among the most polarized issues recently, but this was not always the case, which spurs questions about the development and causes of polarization. Did campaign contributions from special interest groups play any role on the rise of environmental polarization in the US Congress? Is there evidence of a partisan divide on campaign contributions related to environmental legislation? Is there a connection between campaign contributions and the pattern of congressional voting on environmental issues?

How the environment became a polarized issue

With the rise of the environmental movement in the 1970s, the importance of protecting the planet and the natural world became a political issue. Initially support for environmental initiatives was not a clear vote winner or loser, or at least the proportion of expected winners and losers were similarly distributed between both the Republican and Democratic parties. Consequently, bipartisan support for some pro-environmental legislation prevailed, such as the 1973 Endangered Species Act (ESA). Over time, environmental policies with clear positive net benefits and no clearly identified losers diminished and the costs of environmental programs became clear. For example, as the ESA was implemented, landowners often faced high regulatory costs and, importantly, it became clear that the cost and benefits of environmental legislation were not evenly distributed across voters, regions, and interest groups.

The coalitions of interest groups already incorporated into the Republican Party (e.g., more industries associated with natural resources and more rural constituencies) were often negatively affected by environmental legislation. On the other hand, the coalitions of interest groups already within the Democratic Party (e.g., fewer industries associated with natural resources and more urban constituencies) were often positively affected by environmental legislation or, at least, they avoided most of the costs of those initiatives. Thus, environmental interest groups became increasingly attached to the Democratic Party and anti-environmental interest groups became increasingly attached to the Republican Party. Polarization on contributions and lobbying efforts on environmental issues arose as it was easier for pro-environmental interest groups to influence the Democratic Party and for the anti-environmental interest groups to influence the Republican Party.

Once interest groups became more partisan, pro-environmental, or ‘green’ and anti-environmental, or ‘brown’, positions became a routine component of party stances. Subsequently, higher levels of party discipline on the issue were expected and implemented. In some cases, however, local, and regional factors were so strong that some legislators preferred to break party lines, something less common as party polarization set in. As the parties became more focused on different constituencies (e.g., Republicans representing more rural districts and Democrats more urban ones), the divergence in the preferences of the coalitions of interest groups forming the parties also increased, which probably contributed to increase polarization and party discipline as well as to solidify the link between green (brown)- interest groups and the Democratic (Republican) Party.

Photo by Christian Lue on Unsplash

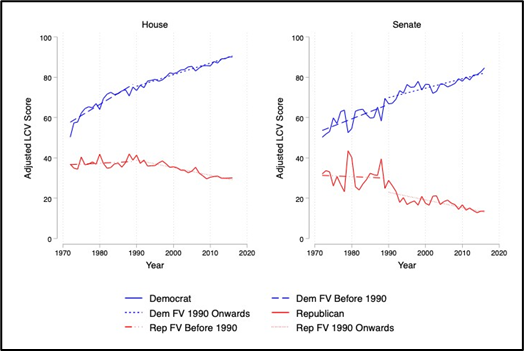

Party Polarization in Environmental Voting

Data from the League of Conservation Voters (League or LCV) confirms the rise in polarization since the relatively bipartisan 1970s. The League creates an annual score for each legislator based on the percentage of pro-environment votes in a set of bills in each legislative session. Figure 1 below shows the average LCV score by political party from 1970 to 2018, for the House and the Senate. A higher LCV means more “green” voting and a lower score means more “brown” voting. The figure also shows the regression line for before and after 1990. Both in the House and the Senate LCV scores are greater for Democrats, and the difference increases over time and the fitted lines indicate that the rate of polarization has increased since the 1990s. Democrats’ LCV scores steadily increase, whereas Republicans’ steadily decrease. Polarization is also apparent when we examine LCV scores in different regions of the US and for specific environmental issues. Democrat (Republican) scores are increasing (decreasing) over time in all regions in both the House and the Senate. We also find similar patterns when we focus on different environmental issues, ranging from air quality to public land management.

Figure 1 – LCV Scores over Time in House and Senate

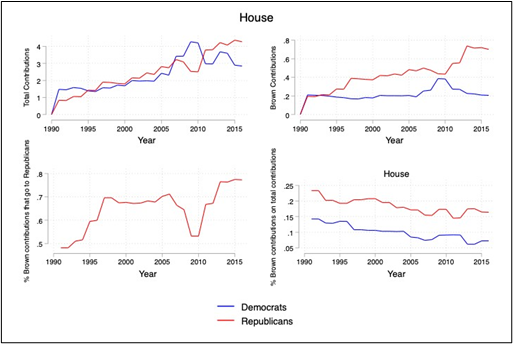

Polarization in Campaign Contributions

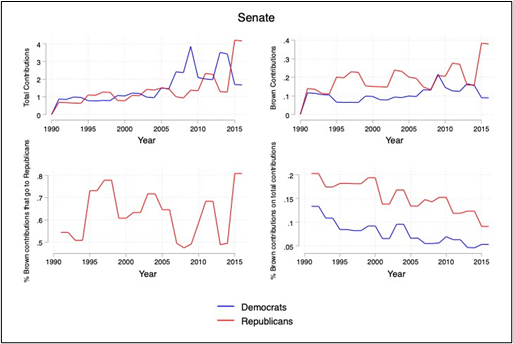

We obtained information on the campaign contributions of interest groups from the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) and identify ‘brown’ industries as those strongly affected by environmental legislation (agriculture; energy, natural resources, and environment; construction and public works; manufacturing; and the subsectors: mining unions, and energy-related unions (non-mining). Figures 2 and 3 show campaign contributions from 1988 to 2017, for the House and Senate, respectively. Total contributions received by legislators have risen to over $300 million for each party. The figures show no systematic difference on total contributions received by Republican and Democratic legislators (see top left panels).

Figure 2 – Brown Contributions in the US House 1988-2017

Figure 3 – Brown Contributions in the US Senate 1988-2017

A different picture emerges when we focus the attention on brown contributions. Brown contributions received by legislators have also risen over time (see top right panels), but Republican legislators have a clear advantage, which can be seen in two different ways. First, a higher share of brown contributions goes to Republican than to Democratic legislators, especially for the House (see bottom left panels). Moreover, for the House, the share of brown contributions going to Republican legislators has been rising over time (except during the G. W. Bush administration). Second, brown contributions represent a more important source of funding for Republican than Democratic legislators (see bottom right panels). Open Secrets does not have information to identify campaign contributions from environmental (‘green’) organizations, but we were able to get contribution data from a few prominent environmental organizations that engage in lobbying. These data suggest that Democratic legislators rely more on campaign contributions from pro-environmental organizations.

Establishing a causal link between partisanship and polarization

Identifying causal relationships in economics and policy is important but often challenging. In our research we aimed to confirm a causal partisan effect on environmental voting and campaign contributions. To do so, we relied on an econometric method which concentrates on studying the behavior of politicians and interest groups in elections that were basically ‘too close to call.’ By focusing on these cases, we can isolate the effect of simply being a Democrat or Republican. This analysis allows us to determine whether party affiliation and ‘partisanship’ causes differences in voting and in contributions by interest groups. Using this method, we obtained two interesting results. First, electing a Republican Congressperson (Senator) rather than a Democrat leads to a decrease in 39.1 (49.7) points in the LCV scores. Second, electing a Republican rather than a Democrat for the House leads to a rise of 96 percent on the importance of brown contributions. In the Senate, electing a Republican rather than a Democrat increases the importance of brown contributions by 70 percent.

Connections between campaign contributions and environmental voting

It is truly hard to find evidence that campaign contributions by brown and green interest groups cause environmental polarization. The data, however, reveal some suggestive correlations. First, we find that greater dependence on brown contributions is associated with lower LCV scores for legislators from both parties in the House as well as in the Senate. Second, we examine which factors predict that a legislator is more likely to break the party line on environmental issues by voting against the party majority. For example, a Democratic legislator from an oil district should be less likely to vote in favor of environmental legislation that negatively affects the oil industry. We find that contributions from brown industries play a prominent role, but the importance of primary activities as well as political characteristics of the legislators sometimes also affect the probability of breaking the party line.

Beyond environmental polarization: toward an interest group theory of parties

Our analysis can be extended to other political issues beyond environmental legislation. More importantly, it suggests a new approach to understanding parties and polarization. The general ideas are that parties should be considered coalitions of special interests, that new political issues might differentially affect initial party coalitions and, therefore, new interest groups might find it easier to lobby one party to the point that in some cases, an interest group becomes attached to one party. Party polarization emerges, expands, or disappears as an outcome from these interactions. In this approach, party polarization rises with the importance of contributions for political campaigns, the level of influence of interest groups, and the more partisan the preferences of interest groups. In particular, the more complementary the preferences over the new issue among the existing coalitions within a party, the more likely the party includes the new special interest group with such preferences. If the other party incorporates interest groups that oppose the new issue, polarization is reinforced.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Campaign contributions, partisan politics, and environmental polarization in the US Congress’, in The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3vGp8UY