New policies at the local, state, and federal level seek to address the problem of food deserts because living far from a supermarket is thought to be related to food hardship and unhealthy eating patterns. In new research, Katie Fitzpatrick and co-authors find little evidence that living in a food desert affects food-related distress among the elderly. Rather, transportation difficulties are more important than limited access to a grocery store. Elderly individuals residing in a food desert without a vehicle are 12 percentage points more likely to report experiencing food insufficiency than food desert residents with a vehicle. Additionally, SNAP recipients living in food deserts are 11 percentage points more likely to receive Meals on Wheels.

New policies at the local, state, and federal level seek to address the problem of food deserts because living far from a supermarket is thought to be related to food hardship and unhealthy eating patterns. In new research, Katie Fitzpatrick and co-authors find little evidence that living in a food desert affects food-related distress among the elderly. Rather, transportation difficulties are more important than limited access to a grocery store. Elderly individuals residing in a food desert without a vehicle are 12 percentage points more likely to report experiencing food insufficiency than food desert residents with a vehicle. Additionally, SNAP recipients living in food deserts are 11 percentage points more likely to receive Meals on Wheels.

More than 18 million people, including almost 5 million elderly, lived in a food desert in 2010. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines a food desert as a low-income area where many residents do not live close to a supermarket. Residents of food deserts face many obstacles in consuming nutritious food, ranging from fewer local stores with healthy food, higher food prices at smaller local grocers, and the time and expense of travelling to a supermarket. As a result, living in a food desert may not only affect the quality of one’s diet, but also the ability to purchase food and other necessities and the need for public food assistance programs.

Compared to other groups, elderly individuals may be particularly affected by food deserts: strong neighborhood ties encourage them to stay in a community even after businesses leave, fixed incomes make paying higher food prices difficult, and physical limitations limit travel. As new policies, ranging from new supermarket development to mobile fruit and vegetable retailers, improve food access for residents of food deserts it is important that they address the needs of the large and growing elderly population.

To understand the relationship between food deserts and both food and material hardship, in new research, we used the 2006 and 2010 Health and Retirement Study (HRS). We selected individuals in the 2006 survey that were: age 60 and older, surveyed in the 2010 HRS, living in urban areas, and had income at or below 200% of the Federal poverty line. We then matched information on where these individuals lived to data on food deserts in 2006 and 2010.

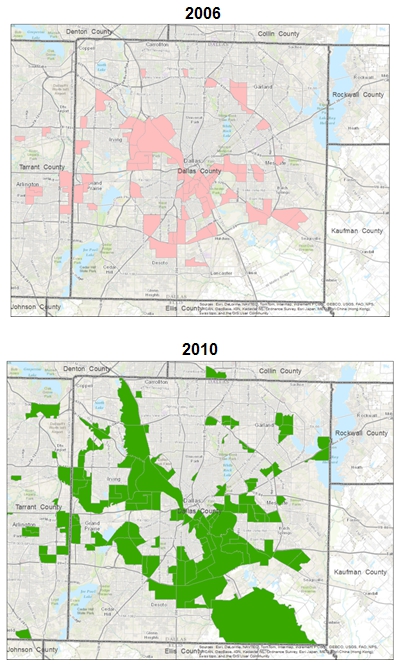

To illustrate our food desert data, Figure 1 presents Dallas County, Texas in 2006 (top) and 2010 (bottom). Portions of Dallas County that were classified as food deserts are shown in color while areas not classified as food deserts are shown in gray. As figure 1 shows, the number of food deserts in Dallas County increased between 2006 and 2010, consistent with the trend nationwide. Some areas were food deserts in both years, but other areas experienced change, as supermarkets closed or opened.

Figure 1 – Food Deserts in Dallas County, 2006 and 2010

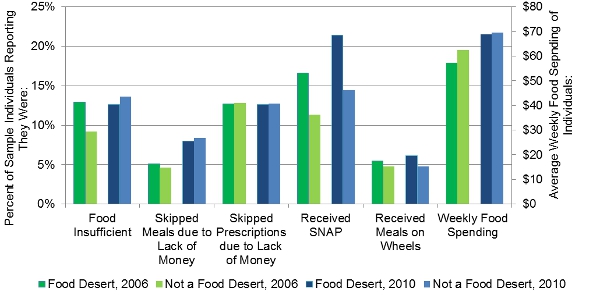

Using this information, in Figure 2 we present simple averages of the experiences of our sample, by food desert status, over the previous two years. These experiences include food insufficiency (a.k.a difficulty purchasing enough food due to lack of money), skipped meals due to lack of money, skipped prescription drugs due to lack of money, SNAP (a.k.a food stamps) receipt, or Meals on Wheels receipt. On average, elderly food desert residents experienced more food insufficiency in 2006 and were more likely to receive SNAP and Meals on Wheels in both years. Moreover, food desert residents spend a similar amount on food each week as those not living outside of a food desert.

Figure 2 – Average Experiences over the Previous Two Years of Sample of Elderly Individuals, by Food Desert Status and Year

We estimate these relationships, controlling for characteristics of the individual and their local area. As in the simple averages, we find little relationship between living in a food desert and experiences of hardship. We only find only that food desert residents are 4.1 percentage points less likely to receive Meals on Wheels than otherwise similar individuals, perhaps suggesting that they have less access to non-profit meal providers.

But, food deserts are only one measure of food access barriers: two individuals have different levels of access if one has a vehicle and the other does not. We found a large correlation between not owning a vehicle and these experiences in our initial analysis. We explored if those without a vehicle in a food desert experience greater hardship. Indeed, food desert residents without a vehicle are most affected by food deserts: they are 12 percentage points more likely to experience food insufficiency and may be more likely to skip meals than food desert residents who owned a vehicle.

Living in a food desert, with or without a vehicle, is not related to other hardships we measure. In fact, participating in Meals on Wheels appears more related to transportation difficulties than living far from a supermarket: individuals without a vehicle are 9 percentage points more likely to receive Meals on Wheels, regardless if they live in a food desert or not.

We also explore if SNAP recipients in food deserts also experience greater hardship. Compared to other food desert residents, SNAP recipients living in food deserts do not suffer greater hardship. However, they are 11 percentage points more likely to receive Meals on Wheels, suggesting that these are complementary programs in the nutritional safety net for those in food deserts.

The importance of transportation burdens

In FY2013, the U.S. government devoted $314 million to improve food access and support healthy food retail development through existing community development programs. The 2014 Farm Bill formalized this effort as the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) by authorizing $125 million to improve access to nutritious food. State and local governments also allocated resources toward improving food access in underserved communities.

Our results indicate that transportation burdens may be more important in determining food and material hardship than whether a senior lives in a food desert. Thus, tackling the problem of food deserts requires greater attention to transportation needs. For example, providing a ride to a supermarket or expanding food delivery for elderly food desert residents may improve their well-being.

Additionally, Meals on Wheels may be helping those lacking a vehicle or who receive SNAP but live in a food desert. If food deserts encourage older Americans to shift from entitlement programs like SNAP to non-entitlement programs such as Meals on Wheels, those at-risk for hunger will be more vulnerable to both the Congressional budget process and the ability of non-profit food providers to meet their needs. This relatively overlooked food safety net program may require additional attention and support.

This article is based on the paper, ‘The Impact of Food Deserts on Food Insufficiency and SNAP Participation among the Elderly,’ authored by Katie Fitzpatrick, Nadia Greenhalgh-Stanley, and Michele Ver Ploeg in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics.

Featured image credit: Anna Vallgårda (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1VrghYL

_________________________________

Katie Fitzpatrick – Seattle University

Katie Fitzpatrick – Seattle University

Katie Fitzpatrick is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Seattle University. Her current work focuses on the effectiveness of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly the food stamp program; the causes and consequences of food insecurity; and, the use of mainstream and alternative financial institutions.

1 Comments