Persuading the public is often a key aim of politicians who are trying to advance their policy agendas. In new research, Matthew D. Luttig and Howard Lavine look at how policies are framed to the public and how this affects support for them. They find that certain framings – such as those which explain how a policy will lead to a gain or loss- are more likely to persuade people to support the policy if it matches with their own motivation towards preventing losses or promoting gains.

Persuading the public is often a key aim of politicians who are trying to advance their policy agendas. In new research, Matthew D. Luttig and Howard Lavine look at how policies are framed to the public and how this affects support for them. They find that certain framings – such as those which explain how a policy will lead to a gain or loss- are more likely to persuade people to support the policy if it matches with their own motivation towards preventing losses or promoting gains.

Democratic theory requires that citizens possess “real” political attitudes with which to guide elected officials. Yet research indicates that mass political attitudes are fickle, and easily change in response to how issues are framed by political elites or the media. For example, public opinion may be more supportive of a policy that is described as “preventing unemployment from exceeding 5 percent” than a policy described as “achieving employment over 95 percent,” even though these policies are equivalent. Mass opinion change in response to these equivalence frames raises serious concerns that the public’s political beliefs are not “sufficiently complete and coherent to serve as a satisfactory starting point for Democratic theory”. Research on prospect theory specifically suggests that humans loathe losses more than they value gains. As a result, elite frames emphasizing potential losses may generate greater policy support than frames emphasizing potential gains, even though the substance of the policy is identical in the two cases.

In our recent research, we argue that framing effects are dependent on a two-way street between how messages are framed and what motivates individual citizens. Drawing on the general concept of functional matching, we argue that equivalence frames that vary only in their respective focus on losses or gains are most persuasive when they “match” an individual’s regulatory focus—a personality variable that captures an individual’s motivational priorities to prevent losses or promote gains. The central claim of our research is that people are more easily persuaded to support a certain policy when the message frame matches with the individual’s regulatory focus orientation (RFO). Second, we expect that this persuasion effect will be most readily apparent among less educated individuals, as better-educated individuals are likely to view policy issues in more overtly political terms such as ideology.

To test these hypotheses, we conducted an experiment that exposed respondents to one of two equivalent frames describing a policy issue. To increase generalizability, we presented respondents with policy statements on eight distinct issues representing a wide range of contemporary policy debates. For each issue, respondents were randomly assigned to either a loss frame or a gain frame. For example, tax cuts were described in the gain frame condition as “additional tax cuts to large businesses to promote the hiring of additional workers.” In the loss frame, this issue was described as “additional tax cuts to large businesses to prevent the firing of additional workers.” These descriptions vary only in their respective emphasis of gains or losses.

As part of the survey and prior to the experimental treatments, we measured respondents’ regulatory focus orientation (RFO) with six items adapted from work by a previous study. To measure RFO, respondents read brief statements, and were asked to indicate how much the statement described someone like themselves. The six items included: “In general, I am focused on preventing negative events in my life;” “I am anxious that I will fall short of my responsibilities and obligations;” “Overall, I am more oriented toward preventing losses than I am toward achieving gains;” “In general, I am focused on achieving positive outcomes in my life;” “Overall, I am more oriented toward achieving success than preventing failure;” and “I frequently imagine how I will achieve my hopes and aspirations.” Agreement with the first three items indicates a relative prevention focus; agreement with the last three items indicates a relative promotion focus.

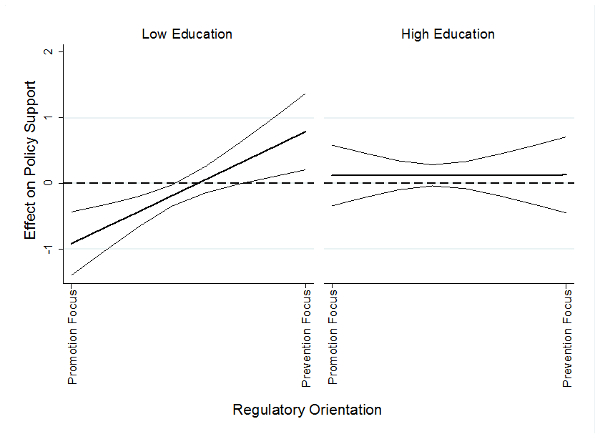

In our analysis, we find consistent support for our expectations. The loss frame increased policy support among individuals with a strong prevention focus, while the gain frame increased policy support among individuals with a strong promotion focus. These effects were also largely confined to less educated respondents, while more educated respondents relied largely on their ideological orientation. Figure 1 below illustrates these results on issues where greater policy support indicates more conservative policy preferences (results are substantively identical on liberal policy issues).

Figure 1 – Average Marginal Effect of Moving from Gain Frame to Loss Frame—Conservative Issues

Notes: Line represents the average marginal change in policy support in moving from the gain frame to the loss frame across levels of regulatory orientation, with 90 percent confidence intervals.

Figure 1 above illustrates that (for less educated respondents) compared to the gain frame, the loss frame increases policy support among individuals with a strong prevention focus. By contrast, relative to the gain frame, the loss frame decreases policy support among individuals with a strong promotion focus.

We believe these findings have implications for the study of the influence of personality in politics and for the effects of policy frames on mass political attitudes. Specifically, our framework offers one potential pathway by which personality traits operate on political preferences, namely, by resonating with how a policy proposal is framed. When an individual’s psychological goals mesh with the language used to describe a policy proposal, they are much more easily persuaded on that policy issue.

Our results show that the effectiveness of equivalent gain and loss frames varies across individuals’ regulatory orientation. This implies that the public’s political attitudes are not automatically or unconditionally susceptible to elite frames. Rather, the success of elite frames, especially those that emphasize the potential gains or losses from a policy, depends on their matching with citizens’ motivational priorities. As a consequence, differences in the public’s regulatory orientation, in the aggregate, can potentially serve as a constraint on attempts by elites to manipulate the public by the framing of policies in terms of potential losses or gains. Therefore, the implication of our results is that public opinion may be less malleable than earlier research on equivalence frames suggested, with individuals playing a more prominent role in their own persuasion.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Issue Frames, Personality, and Political Persuasion’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: GotCredit (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Q28v9B

_________________________________

Matthew D. Luttig – University of Minnesota

Matthew D. Luttig – University of Minnesota

Matthew Luttig is a PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota. His research examines the origins of political extremism, the politics of racial intolerance, and the effects of economic inequality on political behavior.

Howard Lavine – University of Minnesota

Howard Lavine – University of Minnesota

Howard Lavine is Arleen C. Carlson Professor of Political Science and Psychology at the University of Minnesota and Director of the Center for the Study of Political Psychology. He is the author of Cultural Economics: Personality, Parties and the Politics of Redistribution (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming), The Ambivalent Partisan: How Critical Loyalty Promotes Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2012), and Political Psychology (Sage, 2010). He has published articles in The American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the New York Times, and elsewhere. He is past editor of the journal Political Psychology and current editor of the journal Advances in Political Psychology and the book series Routledge Studies in Political Psychology.