Those convicted of a crime are often punished twice; once via the legal system’s formal sanction, and again through the stigma of having a criminal record. Murat C. Mungan argues that the criminalization of many small offenses – such as drug possession – means that this stigma is becoming diluted for more serious criminal offenses. If a large percentage of the population is branded as criminals, he writes, this means that having a criminal record becomes less of marker of a person’s character, no matter if that crime is minor or severe.

Those convicted of a crime are often punished twice; once via the legal system’s formal sanction, and again through the stigma of having a criminal record. Murat C. Mungan argues that the criminalization of many small offenses – such as drug possession – means that this stigma is becoming diluted for more serious criminal offenses. If a large percentage of the population is branded as criminals, he writes, this means that having a criminal record becomes less of marker of a person’s character, no matter if that crime is minor or severe.

When a person is convicted they typically receive a formal sanction such as serving time in prison or paying a criminal fine. Although formal sanctions are what first come to mind when thinking about convictions, simply having a criminal record can also have disastrous effects on people. A person with a criminal record may have a much harder time getting a job compared to person without a record. They may also suffer socially; it may be hard to find or keep friends or romantic partners. All of these negative consequences can collectively be called informal sanctions, the stigma attached to being branded a criminal.

There are many costs associated with this type of stigmatization. Once labeled a criminal, a person has less to lose by committing further crimes. Moreover, the difficulty in finding lucrative jobs may push a person to, even if reluctantly, commit further crimes to support himself financially. Thus, the stigma associated with being branded a criminal can increase recidivism (i.e. the commission of crimes by ex-convicts). On the other hand, stigmatization may cause a reduction in crime by making a criminal career less attractive in the first place (due to the presence of severe informal sanctions). Therefore, the overall effect of stigmatization on crime appears ambiguous.

Despite this ambiguity, many intuit that people who have committed minor crimes are less deserving of stigma than people who have committed serious crimes. Moreover, it seems clear to many that stigmatizing people for minor offenses is likely to have greater costs than benefits due to large recidivism effects dwarfing the potential deterrence benefits of stigmatization. These intuitions may be accurate, and they highlight the potential costs of criminalizing acts that cause minor harms. However, they represent an incomplete depiction of the stigma related costs of criminalizing acts that cause small harms. In particular, criminalizing minor offenses, such as marijuana possession, may cause what I call “stigma dilution.”

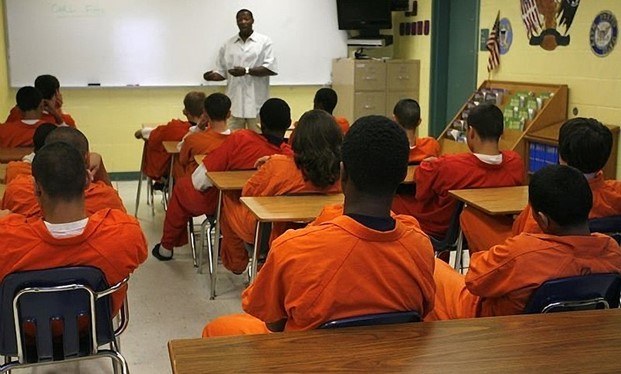

Credit: [puamelia] (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Stigma dilution occurs when the criminalization of a minor offense such as the possession of marijuana leads a sizeable population to be branded as criminals. This increases the size of the criminal population, and reduces the magnitude of the average criminal’s deviation from the average citizen. Thus, people view criminal records as being less informative of a person’s character, which in turn, reduces the informal sanction associated with being a criminal. The result is lower stigma for all sorts of crimes, including serious ones. This leads criminal sanctions to have a lesser deterrent effect and may cause an increase in serious crimes. Stigma dilution becomes a more severe problem when, as is the case in the United States, rap sheets are cryptic and hard (or costly) to decipher, because this makes it difficult to distinguish between criminals based on the severity of the crimes they have committed.

Due to these dynamics, criminalization of minor offenses may cause a trade-off between the deterrence of minor crimes and more serious crimes. Over-criminalization takes place when criminalizing an act causes more harm (however measured) than benefits to society by increasing the number of serious crimes committed. There are some obvious methods to reduce stigma dilution and over-criminalization, and the harms caused by them. First, minor offenses can be classified as civil infractions rather than crimes, and thus their commission would not generate criminal records. Second, certain acts can be completely legalized (which is the case with marijuana offenses in several states in the US (see for instance this Wikipedia entry). Third, one may allow ex-convicts to expunge the records of their minor offenses. The third method may be especially useful for reducing stigma-dilution caused by offenses already committed and may also be used to distinguish between people based on their criminal tendencies (which, as I argue here, can reduce crime even further).

The most popular decriminalization movement in the United States is probably the decriminalization of marijuana related offenses. Needless to say, the decriminalization of marijuana related offenses has obvious benefits besides mitigating stigma dilution. However, the movement is also likely to produce incidental benefits in the form of stigma-restoration (which can be conceived of as the opposite of stigma dilution). This movement can be viewed as a natural experiment which is likely to produce observations that will allow the testing of the theory I have discussed. It should also be noted that there is already some empirical evidence that is consistent with my theory. (See, for instance, a recent study exploiting a policing experiment in London that led to the depenalization of marijuana possession.) Without further empirical observation, it is difficult to determine the size of the social benefits from stigma-restoration; however, these potential benefits should nonetheless be kept in mind while discussing the decriminalization of offenses and other types of lenient criminal law policies.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Stigma Dilution and Over-Criminalization’, in American Law and Economics Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ZgjsEq

_________________________________________

Murat C. Mungan – Florida State University

Murat C. Mungan – Florida State University

Murat C. Mungan, an assistant professor at Florida State University, holds a Ph.D. in economics from Boston College and a J.D. from George Mason University. He teaches students basic accounting, finance theory, and economic analysis.