It has become a well-known fact that per capita, the US imprisons more people than any other country on earth. Despite holding this dubious title, over the last 5 years the US prison population has begun to fall. To explain why the US is sending fewer people to prison, Michelle S. Phelps and Devah Pager look at state-level changes in imprisonment, finding that those states with lower fiscal capacity following the Great Recession and that saw falling rates of violent crime were more likely to reduce their imprisonment rates. They also find that despite the rise of the conservative ‘Right on Crime’ movement, states controlled by Republicans were less likely to see decline in imprisonment rates.

It has become a well-known fact that per capita, the US imprisons more people than any other country on earth. Despite holding this dubious title, over the last 5 years the US prison population has begun to fall. To explain why the US is sending fewer people to prison, Michelle S. Phelps and Devah Pager look at state-level changes in imprisonment, finding that those states with lower fiscal capacity following the Great Recession and that saw falling rates of violent crime were more likely to reduce their imprisonment rates. They also find that despite the rise of the conservative ‘Right on Crime’ movement, states controlled by Republicans were less likely to see decline in imprisonment rates.

A wealth of scholarship now documents the spectacular rise in imprisonment in the United States over the past four decades. During this time, incarceration rates increased more than fivefold, leaving the United States with the highest rate of incarceration in the world. The implications of this dramatic rise in the prison population have yet to receive a full accounting, but a large body of research now points to the serious collateral consequences of mass incarceration. With roughly one in ten men (and one in three black men) expected to serve time in prison during their lifetime, the criminal justice system has become a major source of inequality in contemporary America.

And yet, even as scholars continue to grapple with the causes and consequences of mass incarceration, a new pattern has crept into view that potentially shifts the discussion in important ways. In 2010, the United States’ prison population began to fall for the first time since 1972. Though the size of the decrease has been small—state prison populations declined by just over 3 percent between 2009 and 2013—it marks a notable reversal in a four-decade-long trend. Moreover, the recent national decreases mask substantial variability at the state level over a longer time span, with some states having reduced their incarceration rates by 20 percent since 2000.

In discussions about the potential drivers of this reform, three factors loom large: state budget deficits, declines in violent crime, and the new “Right on Crime” movement that brands criminal justice reform as conservative policy. In our new research, we consider each of these factors in an analysis of state-level changes in imprisonment rates between 2000 and 2013. We ask whether states with the greatest reductions in fiscal capacity and violent crime were the most likely to reduce their imprisonment rates in recent years and if Republican dominance in state leadership is tied with increasing or decreasing prison populations.

Fiscal Crisis

States across the US were hard hit by the fiscal crisis of the late 2000s, which propelled many into an economic tailspin. Leading up to this shock, funding for corrections had been one of the fastest-growing state budget categories in the past decade. Since the early 1970s, the proportion of state funding dedicated to corrections has doubled; by 2008, states spent nearly $50 billion on prisons, probation, and parole. The fiscal crisis gave advocates a compelling argument for reform: mass incarceration was prohibitively expensive.

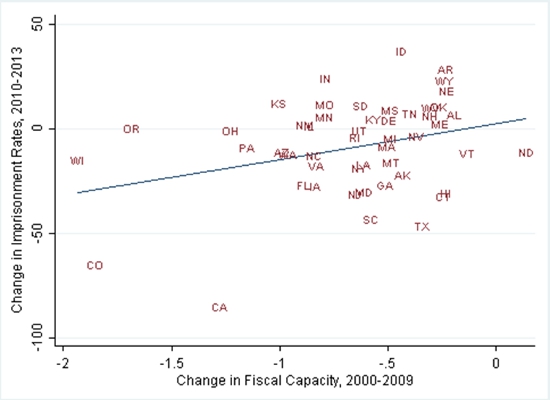

We assess state economic well-being using a measure of fiscal capacity (the logged ratio of state revenue to debt). We find that states with lower fiscal capacity following the recession (in 2010) and those with bigger declines in fiscal capacity in the decade leading up to the recession (2000 to 2009) were significantly more likely to reduce their imprisonment rates in the subsequent three years, as depicted in Figure 1. This suggests that the severity of budget strain did play a role in motivating state leaders to restrain costs by reducing prison populations.

Figure 1 – Fiscal Capacity and Imprisonment

Violent Crime

Beyond the fiscal crisis, commentators have pointed to the record crime lows across the US as a factor driving reforms. Since the early 1990s, violent crime rates have dropped by half. According to the FBI’s statistics, the national murder rate in 2012 was lower than it was in 1961. While research has well established that changes in policy, rather than crime, have been the primary drivers of mass imprisonment, declines in violent crime may facilitate a political context more open to criminal justice reform.

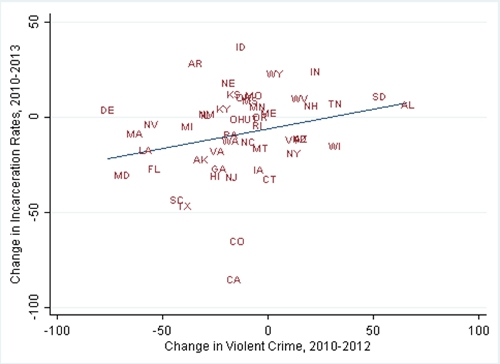

We find that states with greater declines in violent crime in recent years (2000 to 2012) and since the start of the decade (2010 to 2012) were more likely to reduce their imprisonment rates, as depicted in Figure 2. It does appear, then, that reductions in violent crime were important to achieving significant drops in the population behind bars, whether due to their direct link to patterns of punishment or to their influence on the political context in which criminal justice policy is shaped. We also find evidence that states with the largest reductions in prison rates showed no corresponding increase in crime, contrary to the fears of many.

Figure 2 – Violent Crime and Imprisonment

Right on Crime

Much of the story of the rise of mass incarceration focuses on dramatic changes in the politics of punishment—or how crime and punishment are framed in the public arena. The proliferation of criminal justice reforms today have evolved in tandem with a new sensibility around punishment. Rather than competing to be “tough” on crime, political leaders increasingly claim to be “smart” on criminal justice. While the Republican Party has traditionally been identified with a punitive approach, the “Right on Crime” movement has significantly shifted conservative rhetoric. Media commentators and scholars have credited this shift in conservative politics with propelling reform efforts. Has there been a convergence, or even a trading of places, in the criminal justice platforms of Democrats and Republicans?

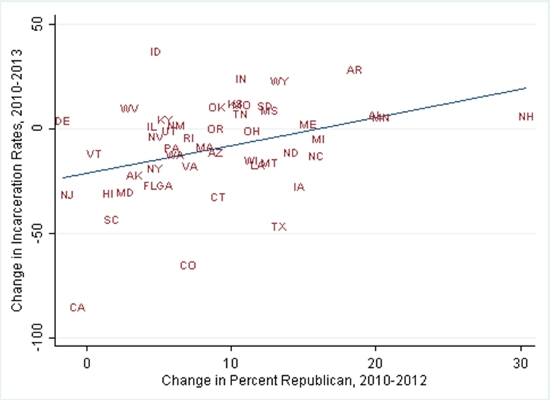

We evaluate these claims by examining the association between states’ political leadership and trends in imprisonment. Contrary to recent rhetoric, we find that Republican leadership–measured by the composition of the state legislature (see Figure 3) and control of the governorship—has little relationship to recent reductions in imprisonment rates. If anything, a strong presence of Republican leadership continues to be associated with expansions of prison populations. This evidence suggests that while conservative criminal justice rhetoric has shifted, Republican states remain laggards in efforts to reduce prison populations.

Figure 3 – Republican Legislators and Imprisonment

Recent trends in states’ prison populations offer a glimpse into a possible future of crime and punishment. Our results suggest that violent crime and budget deficits were correlated with prison reductions, while states with Republican leadership continue to favor tough punishment. While we are clearly not yet at the “end” of mass incarceration, the large declines over the past decade in some states suggest that the recent national downturn is not just a momentary response to the recent financial crisis but, rather, a potential sign of declines for many years to come.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Inequality and Punishment: A Turning Point for Mass Incarceration?’, in The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Featured image cCredit: Niklas Morberg (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1RvNvrS

_________________________________

Michelle S. Phelps – University of Minnesota

Michelle S. Phelps – University of Minnesota

Michelle S. Phelps is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Minnesota and a Faculty Affiliate at the Robina Institute, University of Minnesota Law School, and Minnesota Population Center. Her research is in the sociology of punishment, focusing in particular on the punitive turn in the U.S.

Devah Pager – Harvard University

Devah Pager – Harvard University

Devah Pager is Professor of Sociology and Public Policy at Harvard University. She is the Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. She is the Director of the Harvard Multidisciplinary Program in Inequality and Social Policy and the acting Faculty Director of the Program in Criminal Justice. Her research focuses on institutions affecting racial stratification, including education, labor markets, and the criminal justice system.