For much of Barack Obama’s presidential run and his subsequent two terms as president he has been dogged by accusations that he was not born in the US, and is therefore ineligible to be president. In order to explain the continuing prevalence of this view, despite the evidence to the contrary, Josh Pasek looks at whether or not such ‘birthers’ are motivated by partisanship of racial prejudice. They find that while on the surface the ‘birther’ view is motivated by party ideology and racism, such views actually lead people to dislike President Obama, and thus leaves them more open to accepting claims that he was not born in the US.

For much of Barack Obama’s presidential run and his subsequent two terms as president he has been dogged by accusations that he was not born in the US, and is therefore ineligible to be president. In order to explain the continuing prevalence of this view, despite the evidence to the contrary, Josh Pasek looks at whether or not such ‘birthers’ are motivated by partisanship of racial prejudice. They find that while on the surface the ‘birther’ view is motivated by party ideology and racism, such views actually lead people to dislike President Obama, and thus leaves them more open to accepting claims that he was not born in the US.

According to hospital and state records, Barack Obama was born in Honolulu, Hawaii on August 4th 1961. This fact qualifies him as an acceptable president of the United States under the US Constitution, which requires that any candidate for president be a “natural born citizen” and at least 35 years old. Yet throughout Mr. Obama’s presidential run and his presidency, the legitimacy of his candidacy has been regularly questioned. A vocal group of so-called “birthers” has variously claimed that President Obama was born in either Kenya or Indonesia instead of the United States, an assertion that, if true, would render his presidency illegitimate. And in various surveys between 10 percent and 45 percent of Americans have endorsed this view.

The widespread perception that Mr. Obama was born abroad has been notoriously difficult to counter. In a summary of their examination of the issue as of 2011, Politifact conceded that their fact checking appeared to have little substantive impact. And the proportion of Americans who seem to accept the birther narrative has diminished only slightly over time, even though the Obama campaign and later administration facilitated the release of two separate official birth certificates.

What is it that leads a substantial proportion of Americans to accept a claim with no solid evidence and plenty of available refutation? The work of a number of scholars has suggested that individuals tend to accept rumors and conspiracy theories when those theories support beliefs that they already hold. And this process works especially well in partisan circles, whereby Democrats may be particularly prone to accept negative claims about Republicans and Republicans will be more likely to believe negative things about Democrats. In general, this form of what scholars call “motivated reasoning” is believed to occur because people like to hear information that supports their side and want to challenge information that supports the other side.

In our study, we were interested in two specific factors that might lead people to accept claims that Barack Obama was born overseas: partisanship and racial prejudice. Specifically, we assessed whether conservative Republicans and individuals who held anti-Black sentiments would be more likely to accept the birther narrative than other Americans. And whether, in line with notions of motivated reasoning, they might be expected to accept these claims because they disliked the president.

To understand birther beliefs, we asked a nationally representative sample of 791 non-Hispanic White Americans where they thought Barack Obama was born. We then coded their answers to this question for whether they indicated Barack Obama was born in the United States or outside of the US. The most common answer to this question was some variant of “Hawaii,” but more than 5 percent of respondents asserted that Mr. Obama was born in either “Kenya” or “Africa.” Overall, 72 percent of non-Hispanic White Americans provided answers asserting that Obama was born in the US, 22 percent of individuals provided answers that indicating a non-US birthplace, and another sizable proportion of respondents either asserted that they did not know or provided answers that could not be clearly coded (e.g. “They say in Hawaii, but I don’t believe it”).

To determine whether partisanship and racial prejudice might encourage birther beliefs, we first examined whether non-US responses were more common among White Americans who were conservative Republicans and those who held anti-Black attitudes. Indeed, this was the case. For instance, 94.7 percent of individuals who reported that they were liberal and Democrats asserted a US birthplace as compared to 33.9 percent of conservative Republicans who indicated that the president was born outside of the United States. Similarly, among the most pro-Black individuals, more than 90 percent reported that Barack Obama was born in the US compared with 62.1 percent of the most Anti-Black individuals.

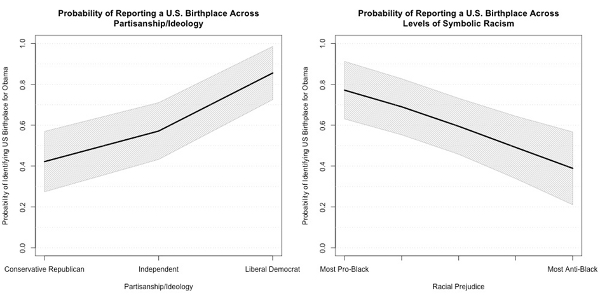

And the strong relations linking partisanship and ideology as well as racial prejudice with perceptions of Obama’s birthplace held when we accounted for demographic differences between individuals and when we assessed for both variables at the same time. Figure 1a shows the chance that an otherwise identical individual would assert a US birthplace for Obama depending on that individual’s partisanship and ideology. Figure 1b shows the same relations for how an identical individual’s claims might be expected to change if that individual had varying levels of racial prejudice.

Figures 1a and 1b – Party ideology and racial prejudice and perception of Obama’s birthplace

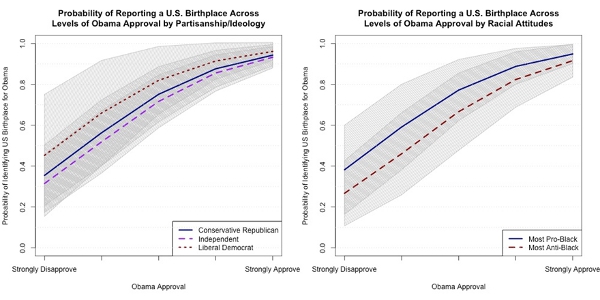

If we accounted for how much people liked or disliked the president’s job performance, however, variations in partisanship and racial attitudes no longer predicted birther beliefs (Figures 2a and 2b). This result suggests that perceptions of the president really account for who accepts the birther narrative. It seems that conservative Republicans and individuals holding anti-Black prejudice do not simply believe that Barack Obama was born overseas because of these views. Instead, being a conservative Republican or an individual who holds anti-Black prejudice likely leads people to disapprove of the president. And it is this disapproval that leaves some individuals open to accepting claims that the president was born overseas.

Figures 2a and 2b – Party ideology and racial prejudice and perception of Obama’s birthplace, accounting for job performance

Collectively, the results of our study support the notion that people are willing to accept rumors and misinformation when doing so reinforces something they already believe. In the case of the birther narrative, individuals who were predisposed to dislike the president were much more likely to believe birther rumors than those who viewed Mr. Obama in a more favorable light. But it was the process of disliking the president that seemed to allow people’s predispositions to translate into inaccurate beliefs.

This article is based on the paper, ‘What motivates a conspiracy theory? Birther beliefs, partisanship, liberal-conservative ideology, and anti-Black attitudes’, in Electoral Studies.

Featured image credit: News Fedora (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1PCruoM

_________________________________

Josh Pasek – University of Michigan

Josh Pasek – University of Michigan

Josh Pasek is Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Michigan. His research explores how new media and psychological processes each shape political attitudes, public opinion, and political behaviors. Josh also examines issues in the measurement of public opinion including techniques for reducing measurement error and improving survey design. Author photo credit: University of Michigan Photo Services, Austin Thomason.

Birthers have long pointed out to those who would listen, birtherism has absolutely nothing to do with the color of one’s skin. Obama wasn’t the only, nor even the first, 2008 presidential candidate sued in federal court over his Art. II, §1, cl. 5 natural born citizen qualifications. Those dubious honors belong to John McCain. In fact, just the opposite is true. It would have been racist not to question Obama qualifications given his unique history. The fact that Obama, himself, admits his father was a British subject at the time he was born, and by ‘descent’, he, too, was born a foreign national, is more than enough to question his presidential qualifications without being accused of racism. True, this is not how our courts have looked at this issue, but it is a legitimate question of constitutional law, which has nothing to do with the color of one’s skin.

The same applies to Sen. Cruz. His father, like Obama’s, was not a US citizen at the time of Ted’s birth. Both Obama and Cruz are US citizens at birth via positive (man-made) law. They are not natural born citizens, which does not require the enforcement of any positive law to acquire US citizenship at birth. If you were born of two citizen parents, or even one US citizen parent if unmarried, or the other parent was deceased, or unknown at the time of your birth, and you were born within the boundaries of this country, you were born a natural US citizen. If you were born via the 14th Amendment or other statutory law, in Sen Cruz’s case via Title 8 USC §1401 (g), you are a naturalized US citizen at birth. This has nothing at all to do with the color of someone’s skin.

Herman Cain, Ben Carson, and Al Sharpton are just as much natural born citizens as Trump, JEB, or Hillary Clinton, to name a few. The natural born citizen requirement wasn’t meant to be a barrier to those citizens of the United States who were exclusively born under U.S. sovereignty, with not foreign allegiances or attachments.