Last week saw the Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump nominate his vice presidential candidate in the form of Indiana Governor, Mike Pence; Hillary Clinton will soon announce her own candidate. Joseph Uscinski writes that the way such vice presidential candidates are selected has become progressively less democratic, with the process now in fewer and fewer hands. He also warns that if presidential candidates select a vice president who differs substantially from them in terms of their policy positions in order to gain electoral advantage, then this can create incentives for Congress to remove the Commander-in-Chief.

Last week saw the Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump nominate his vice presidential candidate in the form of Indiana Governor, Mike Pence; Hillary Clinton will soon announce her own candidate. Joseph Uscinski writes that the way such vice presidential candidates are selected has become progressively less democratic, with the process now in fewer and fewer hands. He also warns that if presidential candidates select a vice president who differs substantially from them in terms of their policy positions in order to gain electoral advantage, then this can create incentives for Congress to remove the Commander-in-Chief.

Every four years spectators watch as the presumed American presidential nominees consider and finally choose their vice-presidential running mates. Donald Trump announced his selection of Indiana Governor Mike Pence last week; Hillary Clinton is expected to announce her choice following the Republican convention. The media cover the selection processes as if they were a parlor game, predicting which party can gain an electoral advantage by choosing which potential running mate.

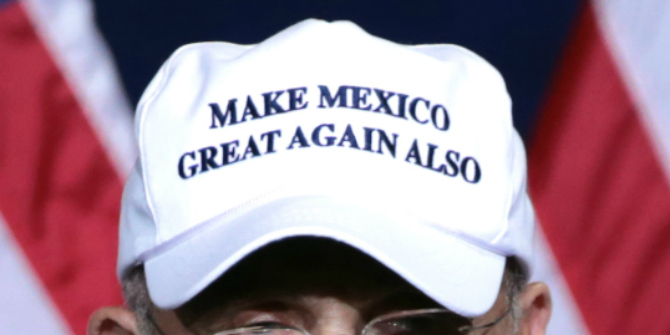

To increase their chances of winning, presidential candidates often choose vice-presidential candidates who differ from them in important ways. Trump’s choice of Mike Pence, a social and establishment conservative, was largely intended to solidify the Republican base by showing deference to the faction of the Republican Party Trump does not appeal to on his own. Hillary Clinton’s potential choices remain shrouded, but it is likely that the electoral map and existing divisions in the Democratic Party will factor into her choice.

On one hand, “balancing” the ticket with differing individuals provides a normative value: having a president and vice president who vary in their positions may deliver broader representation and more balanced governing. On the other hand, the winning coalition that chose the presidential nominee may not have chosen the nominee’s running-mate; instead, they would have preferred a vice-presidential candidate more similar to the nominee. Furthermore, vice-presidents tend to fall into obscurity after the election, and there is no guarantee that the vice-president will have any say in policy.

The selection of vice-presidents has fallen into fewer and fewer hands, making it less democratic. Vice presidents were originally elected by the electorate, but more recently presidential candidates have singlehandedly selected their running mates with input only from close advisors. This is in opposition to the general trend toward more inclusivity in US elections.

The undemocratic nature of the selection process has an upside, however. By giving the choice of running mate to the presidential candidate, the candidate could select a running mate who shares their policy views. This would provide stable policy and a seamless transition should the president unexpectedly leave office. This is important for democracy: should the country choose a president offering a set of policy positions for a four year term, they should be governed by those policy positions for the term’s duration. An unexpected death or removal should not upend majority rule. But, when presidents and vice presidents differ in considerable ways the country could inherit a leader espousing policies the country does not democratically support, and beyond this, a perverse set of political incentives are created.

When a president unexpectedly leaves office, the vice president can put national policy in line with her own preferences. To reference the Godfather, this creates a “Sonny and Vito problem.” A dissimilarity between the president and vice president incentivizes assassination as an advantageous way to single-handedly change policy, and it also incentivizes Congress to remove a president for political rather than criminal reasons. Macabre for sure, but the incentives for fanatics are real.

Paradoxically, while electoral incentives continue to entice presidential candidates to pick vice presidents different from themselves, the expected electoral benefits are rarely realized. Some studies show that a vice-presidential candidate can swing their home state in certain circumstances; however, most research suggests that people vote for the names on the top of the ticket with vice-presidential candidates having little effect on general election outcomes.

As we think about Donald Trump’s choice of Mike Pence, or of Hillary’s forthcoming choice, we should move away from the electoral considerations. Instead, we should focus more on the prospect of succession. Unexpected succession is not uncommon: nine or one fifth of all US Presidents succeeded because of the death of the sitting president. Gerald Ford entered the White House after Richard Nixon’s resignation. These ten presidents served a total of forty-two years. Because of this, we should encourage candidates to pick running mates who can ensure stability, continuity, and democratic outcomes for the full four years of the presidential term.

This post summarizes arguments in “Smith (and Jones) Go to Washington: Democracy and Vice-Presidential Selection” published in PS: Political Science & Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2adNrgl

_________________________________

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

Joseph E. Uscinski is Associate Professor of Political Science at University of Miami College of Arts & Sciences and coauthor of American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford University Press, 2014).