We know that watching partisan media makes people feel more negative towards political parties that they oppose, but what about the mainstream media? In a study of mainstream news media coverage of the 2008 election, Glen Smith finds that those who watched coverage of the presidential candidate on ABC, CBS, NBC, and PBS news became more positive to the leaders of the party that they opposed.

We know that watching partisan media makes people feel more negative towards political parties that they oppose, but what about the mainstream media? In a study of mainstream news media coverage of the 2008 election, Glen Smith finds that those who watched coverage of the presidential candidate on ABC, CBS, NBC, and PBS news became more positive to the leaders of the party that they opposed.

The relationship between the political parties in the United States has grown sour over the last thirty years. Partisans increasingly dislike and distrust leaders of the opposing party, which makes legislative compromise politically troublesome. After all, if the opposing party is evil, compromise is akin to making a deal with the devil. Many have pointed to the news media as being partly responsible for increasing hostility between the political parties, and there is plenty of evidence that watching Fox News or MSNBC makes partisans more negative toward leaders in the opposing party. With all of the attention paid to partisan media however, few have considered whether mainstream news might decrease partisan hostilities.

My work shows that mainstream media make partisans less hostile toward opposing party leaders by exposing viewers to competing arguments. Unlike partisan media outlets, mainstream news strives to present competing perspectives when covering politics. Such balanced coverage is enforced by common journalistic practices requiring that arguments from both parties are included in political stories. The result is a venue where partisans can hear strong arguments opposing their perspectives. Exposure to this cross-cutting discourse on mainstream news is increasingly important as people are more likely to live in politically like-minded communities and avoid political discussions with opposing partisans.

When people are not aware of opposing arguments, they often attribute political disagreements to negative causes, such as ideological bias, ignorance, self-interest, lying, or some ulterior motivation. Additionally, studies show that people tend to believe that members of social out-groups (groups which they aren’t a member of) act in more stereotypical ways than members of in-groups. For example, when it comes to assistance for the needy, liberals see conservatives as heartless while conservatives see liberals as bleeding hearts. Attributing disagreement to these negative stereotypes lead people to see their political opponents as more ‘evil’ than they actually are.

Mainstream media challenges these misperceptions by exposing partisans to the actual arguments made by opposing political leaders. Learning about other viewpoints can increase tolerance by focusing attention on shared values and similarities. Understanding that opposing viewpoints are based on rational arguments can challenge stereotypes and reduce antipathy toward the opposition.

To examine how mainstream news affects negativity toward political leaders, I used survey data from internet portion of the National Annenberg Election Survey, which was conducted online during the 2008 presidential election. Negativity toward opposing candidates is measured by asking respondents how they felt about each presidential candidate from 0 (cool and unfavorable) to 100 (warm and favorable). Exposure to mainstream media was measured as the total number of broadcast news programs (out of 10) on ABC, CBS, NBC, and PBS that respondents reported watching in the last month.

Overall, those watching more broadcast news programs were more positive toward opposing party leaders, even after controlling for ideology, education, age, and exposure to partisan media. Following the 2008 election, those watching 7 or more broadcast programs were roughly 13 points more favorable toward Obama than Republicans watching no broadcast programs. Meanwhile, Democrats that watched 7 or more programs were about 6 points more favorable toward Senator John McCain than Democrats that watched no broadcast programs. In other words, those watching more broadcast news were less negative toward opposing politicians.

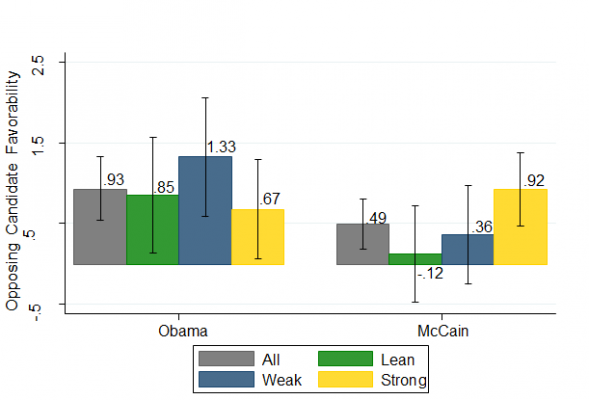

Of course, these results could be explained by self-selection into the broadcast audience. It is certainly possible that broadcast news is more attractive to viewers with lower levels of antipathy toward opposing candidates. To address this possibility, I estimate a fixed-effects regression model that compares each person to themselves at different points in time. Figure 1 shows the predicted change in opposing candidate favorability when someone watches one additional program over the course of the election. The grey bars show the effects of broadcast news on all partisans, while the other bars show the effects on strong, weak and lean partisans. For the sake of brevity, I only present the effects on opposing political leaders, but the results provide no evidence that broadcast news affected attitudes toward in-party candidates.

Figure 1 – The Effects of One Additional Program on Opposing Candidate Favorability

Note: Bars represent the predicted change in opposing candidate favorability when partisans watch one additional broadcast news program. I-bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Among all partisans, watching one additional program increased Republicans’ favorability toward Obama by roughly one point, and increased Democrats favorability toward McCain by nearly a half point. Interestingly, broadcast news also increased opposing candidate favorability among partisans who strongly identified with their political party. Since those with strong partisan attachments are more hostile toward opposing partisans, these results suggest that broadcast news lowers negativity among the types of people that need it most.

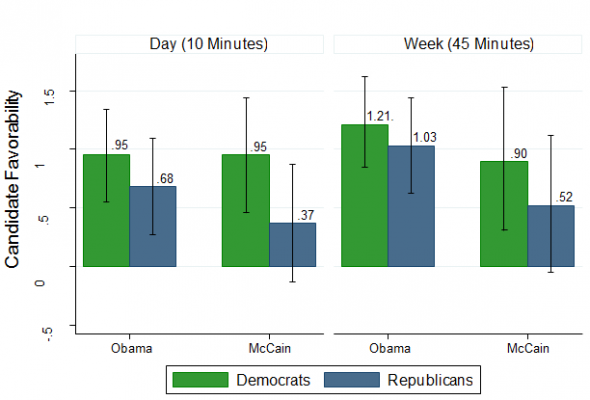

Figure 2 – Change in Candidate Favorability Following Increased Coverage

Note: Bars represent the expected change in opposing candidate favorability among respondents interviewed the day and week following increased broadcast news coverage. I-bars show 95% confidence intervals.

To supplement the previous analysis, Figure 2 shows whether increased coverage of the presidential candidates on broadcast news was followed by increased positive impressions of the candidates among opposing partisans interviewed the following day and week. If increased coverage precedes changes in feelings toward the candidates, it provides further evidence that broadcast news affects viewer attitudes. An additional 45 minutes of Obama coverage per week predicted a 1.03 point increase in Republican favorability the following week. Likewise, Democrats’ favorability toward McCain increased by nearly one point (.90) following an additional 45 minutes of coverage the previous week. Once again, the results provide no evidence that broadcast news decreased favorability toward either candidate. In short, when broadcast news spent more time talking about the presidential candidates, opposing partisans became more favorable the following day and week. Whether those effects lasted throughout the election is unclear, but it is possible that these small weekly changes accumulated over the course of the election.

Overall, these results suggest that increased exposure to mainstream media predicts increased favorability toward political leaders in the opposing party. With opinion polls pointing to an increasingly polarized public, and the role partisan media plays in increasing negativity, this research provides some evidence that mainstream media outlets may be moving public opinion in a more positive direction. Furthermore, these results underscore the importance of the balance norm in professional journalism. It is common practice for journalists to present arguments from both political parties in news stories. While the balance norm is not without its problems—such as treating all arguments as equally valid—this research shows that presenting both sides reduces negativity by exposing partisans to the arguments from opposing candidates. Although mainstream news is certainly not a panacea for partisan antipathy, it appears to play a role in softening some of hostility between the two parties.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Sympathy for the Devil: How Broadcast News Reduces Negativity Toward Political Leaders’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Ernst Moeksis (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2aMiajR

_________________________________

Glen Smith – University of North Georgia

Glen Smith – University of North Georgia

Glen Smith is an Associate Professor at the University of North Georgia. His research focuses on partisan media and political tolerance. He has recently published journal articles examining the effects of partisan media on public opinion.

1 Comments