Since the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling on Citizens United v. FEC, the spending and influence of outside interests in US elections has ballooned. But which groups are spending on what, and does this spending actually change the issues focused on in campaigns? In new research, Michael Franz, Erika Franklin Fowler, and Travis Ridout examined televised political advertising from 2008, 2010 and 2012. They find that outside group sponsorship has moved towards multi-issue non-membership groups, and that these groups match some of their issue discussions to those of their preferred candidates at rates similar to party-sponsored advertising. They also find that these groups show little “issue leadership”, and do not generally move candidates to focus on certain issues.

Since the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling on Citizens United v. FEC, the spending and influence of outside interests in US elections has ballooned. But which groups are spending on what, and does this spending actually change the issues focused on in campaigns? In new research, Michael Franz, Erika Franklin Fowler, and Travis Ridout examined televised political advertising from 2008, 2010 and 2012. They find that outside group sponsorship has moved towards multi-issue non-membership groups, and that these groups match some of their issue discussions to those of their preferred candidates at rates similar to party-sponsored advertising. They also find that these groups show little “issue leadership”, and do not generally move candidates to focus on certain issues.

By all accounts, American elections have undergone some dramatic structural changes in the last few years. Most prominently, in the aftermath of the historic Citizens United v. FEC Supreme Court ruling in 2010, Super PACs and other interest groups (like some non-profits) have become increasingly active in American campaigns. Their increased investment is a source of deep anxiety for many Americans. Among numerous concerns, many fear that outside groups will hijack American elections by controlling the issue agendas of campaigns, taking that power away from candidates. Such agenda-setting powers may harm citizens’ ability to hold candidates accountable along with candidates’ ability to understand what voters want. In short, communication between candidates and voters could be muted amidst the din of outside group campaign ads. These are serious concerns, and yet they remain largely hypothetical; empirically we know very little about what outside groups are saying in their political ads, beyond attacking candidates they don’t like.

We begin by noting that outside group influence on American elections come in many different shades and varieties. The common focus is on the Super PAC, a type of organization sanctioned in the legacy of Citizens United that allows donors to raise and spend unlimited resources in support of or in opposition to federal candidates. But outside groups are not monolithic. We examine two key characteristics: a group’s issue focus (is it broad or narrow?) and their formal membership base (does it have one or not?). Putting these two characteristics together, we arrive at four different types of groups: the single-issue membership groups (e.g., the Sierra Club and National Rifle Association), single-issue non-membership groups (e.g., America’s Agenda Healthcare for Kids and Mainers for Employee Freedom), multi-issue membership groups (e.g., MoveOn.org and the Chamber of Commerce), and multi-issue non-member groups (e.g., Let Freedom Ring and American Future Fund). These last groups are the ones most likely to be Super PACs and non-profits, broad in focus but without formal members (who pay dues and/or help shape group interests). We use television political ad data from the Wisconsin Advertising Project in 2008 and the Wesleyan Media Project in 2010 and 2012 to track advertising by these groups. We focus our analysis on races for the US Senate.

We are interested in three types of analyses. First, how is political ad spending distributed across these group types? Second, what is the level of issue overlap in political ads from outside groups with the ads from the candidates they support? Third, is there any evidence that groups are refocusing the issue debates in campaigns away from the preferred issue focus of candidates?

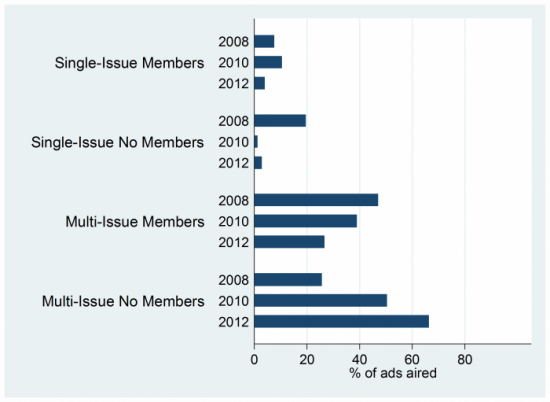

On the first question, Figure 1 shows that the sponsorship of outside group advertising has shifted toward multi-issue non-membership groups in recent years. Whereas only about a quarter of outside group ads came from multi-issue non-membership group sponsors in 2008, such groups accounted for over 60 percent of group advertising in 2012. The rise of amorphous and shadowy super PACs is apparent in these data.

Figure 1 – Involvement of Interests Group by Type, 2008-2012

Source: Wisconsin Advertising Project and Wesleyan Media Project

But this merely inspires the second question—what are the levels of issue overlap between group and candidate ads? To investigate, we looked at the set of ads aired by groups and candidates to calculate a measure of “issue convergence” between pairs of ad sponsors. The resulting convergence scores range from 0 (where each sponsor spoke about wholly different sets of issues) to 1 (where the sponsors devoted the same proportionate attention to the same set of issues). We calculate these for each set of sponsors in each Senate race for ads aired in blocks of two-weeks between September and Election Day.

All told, we found low to moderate levels of “issue convergence” between candidates and their allied groups. This is demonstrated in Figure 2; mean convergence is well below 1. This implies that candidates and groups are, by and large, not speaking about the same issues. Still, the level of convergence between a group and its preferred candidate is a function of the type of group, namely, whether it focuses on a single issue and whether it has members. We find that multi-issue, non-membership groups are more likely than single-issue membership groups to focus on issues similar to their preferred candidates. Not shown in Figure 2, but important to note, is that issue convergence between candidates and multi-issue, non-membership groups is similar to levels of convergence between candidates and ads from their formal party organization. In short, groups like Priorities USA and Crossroads GPS (two groups highly invested in American elections) are acting a lot like parties, partially matching their issue discussions to that of the candidates they support.

Figure 2 – Issue Convergence between Groups and Candidates by Group Type (2008-2012)

Notes: Differences across multi and single-issue bars are significant at p<.05, Differences across nonmember and membership groups are significant at p<.05 for multi-issue groups and Total. Unit of analysis is a group in a Senate race/market/two-week period

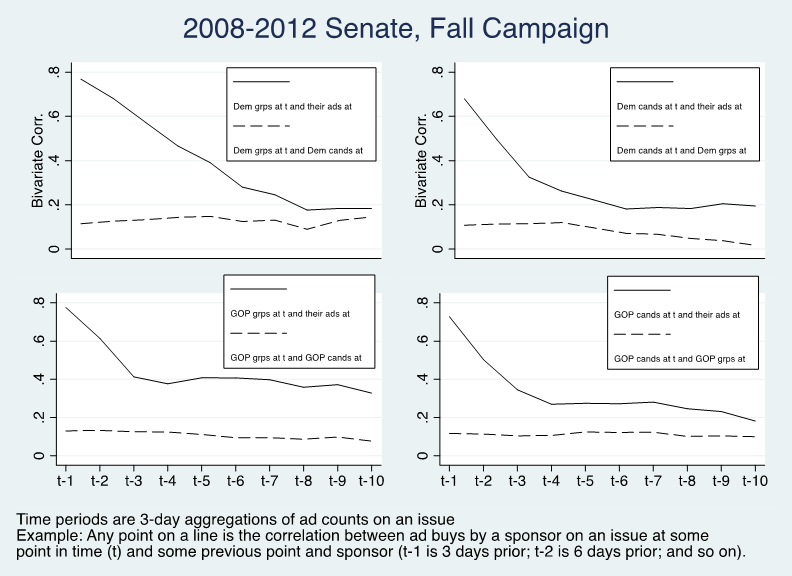

Variation in issue convergence across groups is only part of the story, however. A key concern for many is whether groups drive the convergence we see (where groups pull candidates to advertise on certain issues), or whether it is the other way around. This is not easy to investigate. For this, we take a slightly different tack. For a pair of sponsors in a race, we count the number of ads that reference each issue on our coding sheet. We do this in 3-day blocks of time. We then correlate issue mentions of the group and the candidate in the block and in previous 3-day blocks. High correlations would suggest the sponsors’ issue mentions are similar.

We show results in Figure 3, lumping all candidate/group pairs together. Most importantly, one’s own advertising in the previous few time blocks (whether it be groups or candidates) is most strongly related to issue mentions at any point. That effect starts to trail off pretty quickly (such that what you advertised on a month ago doesn’t tell you much about what you are doing now). Note the relatively weak correlations across sponsors (the dashed lines). In short, there doesn’t appear to be much “issue leadership” from groups or candidates, though the correlations do trail off a bit, meaning there is some (small) effect in moving a candidate or group to advertise on certain issues.

Figure 3 – Correlation of Issue Mentions across Time and Sponsor

These are just correlations, keep in mind, but interesting ones nonetheless and consistent with more complex tests we run on our data. The results conflict with a story of agenda hijacking from outside groups in campaigns. What any political actor chooses to talk about in its ads is driven by factors beyond what one’s allies are saying in their spots. To the extent we find more convergence between the issues groups are discussing and the issues candidates are discussing, we are more likely to find it among multi-issue non-membership groups than among single-issue membership groups.

Of course, convergence can be viewed through different lenses. As Super PACs and other groups expand their presence in elections voters may be exposed to an array of new and important issues that candidates might otherwise ignore. Voters may benefit under a “more speech is better” interpretation of these results.

On the other hand, when campaigns feature discussion of more issues, the potential for voter confusion rises. Group advertising may direct voters’ attention in many directions and make it difficult for voters to hold candidates accountable for what they say. Perhaps more importantly, it might make it harder for winning candidates to know what to advocate for when elected to office. The issue narrative of a campaign is a whole lot messier as more groups become involved in the election. There can be no mandate for policy-making, such that one exists, if it is not clear what messages or issues persuaded critical voters.

The results thus far suggest both good and ill effects. We feel confident in saying that fears of outside groups – particularly those encouraged by the current campaign finance landscape – “hijacking” campaign agendas appear unfounded, and this is no small thing. The balance sheet on the implications may change, however, as we continue to track what outside groups are saying in American elections. We have data on the 2014 mid-terms—yet to be added to this analysis—and we are in the process of collecting and coding ads from this cycle, thus far a banner year for outside group electioneering. We can say for certain this, indeed: the work continues.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Loose Cannons or Loyal Foot Soldiers? Toward a More Complex Theory of Interest Group Advertising Strategies’ in the American Journal of Political Science.

Featured image credit: Public Citizen (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2d3nl27

_________________________________

Michael Franz – Bowdoin College

Michael Franz – Bowdoin College

Michael M. Franz is Associate Professor at the Department of Government and Legal Studies at Bowdoin College.

Erika Franklin Fowler – Wesleyan University

Erika Franklin Fowler – Wesleyan University

Erika Franklin Fowler is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University where she directs the Wesleyan Media Project, which tracks and analyzes all political ads aired on broadcast television in real-time during elections. Fowler specializes in political communication – local media and campaign advertising in particular – and her work on local coverage of politics and policy has been published in political science, communication, law/policy, and medical journals.

Travis Ridout – Washington State University

Travis Ridout – Washington State University

Travis N. Ridout is Thomas S. Foley Distinguished Professor of Government and Public Policy at the School of Politics, Philosophy and Public Affairs at Washington State University. His broad areas of research interest include political communication, voting, elections and campaigns, political participation, presidential nominations and survey methodology.

1 Comments