Last month Hillary Clinton stepped into controversy when she described ‘half’ of Donald Trump’s supporters as a ‘basket of deplorables’. In a new study, Karen L. Blair looks at how Clinton and Trump voters’ attitudes on themes such as sexism, authoritarianism and Islamophobia differ. She finds that Islamophobia is closely linked with support for Trump, and that the strongest predictor of voting for someone other than Clinton or Trump was not disagreeing with Clinton ideologically, but ambivalent sexism.

Last month Hillary Clinton stepped into controversy when she described ‘half’ of Donald Trump’s supporters as a ‘basket of deplorables’. In a new study, Karen L. Blair looks at how Clinton and Trump voters’ attitudes on themes such as sexism, authoritarianism and Islamophobia differ. She finds that Islamophobia is closely linked with support for Trump, and that the strongest predictor of voting for someone other than Clinton or Trump was not disagreeing with Clinton ideologically, but ambivalent sexism.

On September 9th, 2016, Hillary Clinton gave a speech at the LGBT for Hillary Gala in New York City in which she referred to ‘half’ of Donald Trump’s supporters as a ‘basket of deplorables’ who espouse ‘racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic [and] Islamophobic’ sentiments. Although Clinton had prefaced her comments by acknowledging that she was about to make an overgeneralization, the backlash to her comments was swift, with Trump charging that her comments showed her true ‘contempt for everyday Americans’. Clinton apologized for her remarks, but doubled down in depicting Trump’s campaign as one based in ‘bigotry and racist rhetoric.’ Was there any truth to Hillary Clinton’s depiction of Trump supporters? To what extent can American voters for various candidates in this election be distinguished from each other on the basis of their attitudes? Can supporters of the various presidential candidates be differentiated by measures related to some of the key themes in the 2016 election, such as authoritarianism, sexism, Islamophobia, racism, and attitudes towards LGBTQ individuals?

In an attempt to understand more about how voters differ from each other as a function of their attitudes, I went back to a dataset collected between the spring of 2014 and the fall of 2015. As part of a study on another topic, 465 individuals, mostly from Utah, and mostly men, completed an online survey which included measures of attitudes towards the LGBTQ community (modern homonegativity, old-fashioned homophobia, genderism, and transphobia), racism, Islamophobia, ambivalent sexism (the combination of both hostile and benevolent feelings towards women), and indicators of conservative ideology (right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, protestant work ethic, and religious orientation). On September 28th, 2016, two days after the first presidential election, I re-contacted these participants and asked them whom they were planning to vote for in the presidential election. Over the following week, 249 responded and indicated their intentions to vote for Clinton, Trump, various third party candidates, or that they were as of yet, still undecided.

Although the sample was not a representative cross-section of American voters, therefore not giving a reliable indication of how many voters plan to vote for each candidate, my analysis can shed light on the associations between attitudes measured up to two years ago and voting intentions. Within this particular sample, 38.5 percent indicated that they planned to vote for Clinton, 24.5 percent indicated they planned to vote for Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson, 11.6 percent for Trump, 15.3 percent undecided, with the remainder indicating other third party and write-in candidates. For ease of comparison, voters were put into one of three groups based on whether they were voting for Trump, Clinton, or a third party candidate or were undecided.

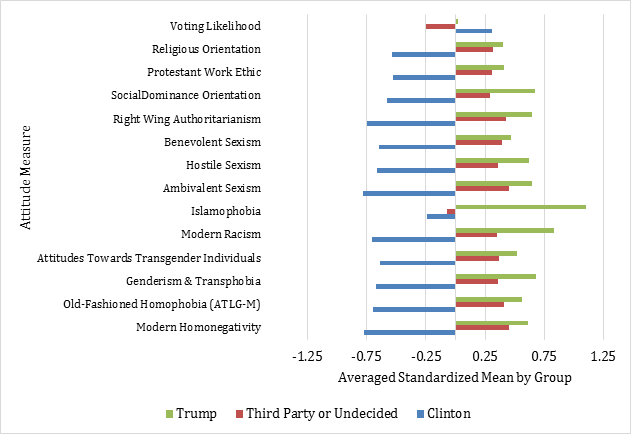

Figure 1 demonstrates how the voters in these three groups differ on the attitude measures collected in 2014 and 2015, as well as their intention to vote in the upcoming election on a scale ranging from 0 (not voting) to 10 (absolutely voting). Because each of the measures used a different response scale, for example, Islamophobia is measured on a scale that goes from 1 to 5 and Social Dominance Orientation is measured on a scale that goes from 1 to 7, the means for each measure for the full sample were standardized. Figure 1 shows the group means of these standardized scores for each of the groups of voters, divided by the candidate that they are planning to vote for. In addition to Figure 1, which visually demonstrates the group differences, I ran analyses to assess the statistical significance of these group differences.

Figure 1 – Group differences in attitudes

Clinton voters in this sample reported significantly more positive attitudes towards a number of groups within our society, including gay men, transgender and gender diverse individuals, women, and ethnic minorities. Clinton voters also showed significantly lower levels of Islamophobia than Trump voters, but were not significantly different on this measure compared to voters who were still undecided or planning to vote for a third party candidate. In other words, given Clinton’s definition of ‘a basket of deplorables’ as being people who hold ‘racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic [and] Islamophobic’ sentiments, Trump supporters do appear to exemplify these qualities in comparison to Clinton supporters.

In addition to holding different views about specific groups of people, Clinton voters were also distinguishable from Trump and undecided/third party voters in their views about how the world and society should be structured and should function. Specifically, Clinton voters had significantly lower levels of authoritarianism and were less likely to subscribe to a hierarchically ordered sense of society (social dominance orientation). Clinton voters also tended to be less religious than both Trump and undecided/third party voters. In all cases, the effect sizes for these group differences were large.

Although Trump and undecided or third party voters could not be distinguished from each other on the vast majority of measures, they did significantly differ from each other on two variables: Islamophobia and intentions to vote. With respect to Islamophobia, Trump supporters are set apart from both Clinton and those still undecided or planning to vote third party. Indeed, this may be the strongest deterrent to voting for Trump for many of the undecided and third party voters. Regression analysis revealed that individuals were more than 3 times more likely to vote for Trump for every step they increased on the Islamophobia scale and 2.6 times more likely to be undecided or voting for a third party candidate for every step that they decreased on the Islamophobia scale.

If higher levels of Islamophobia predict a vote for Trump, why do lower levels of Islamophobia not universally predict a vote for Clinton? Indeed, Islamophobia was not a significant predictor of voting for Clinton over any other candidate, despite levels of Islamophobia among Clinton voters being equal to or less than those within the undecided or third party group. The variable that played the strongest role in predicting a vote for Clinton was lower levels of ambivalent sexism, such that for every point decrease on the ambivalent sexism scale, individuals were 3.3 times more likely to indicate an intention to vote for Clinton. Higher levels of ambivalent sexism were also predictive of being an undecided or third party voter, such that for every step up on the ambivalent sexism scale, participants became 2.5 times more likely to be undecided or to pick a third party candidate. In other words, it appears that while lower levels of Islamophobia are pulling undecided and third party voters away from Trump, the higher levels of ambivalent sexism among these same voters are pulling them away from Clinton and directing them towards the undecided or third party candidate category.

Further, in regressions to predict voting for Clinton or not, voting for Trump or not, and being an undecided or third party voter or not, attitude measures were the strongest, and often only, significant predictors of voting intentions. All three analyses included: old-fashioned homophobia, Islamophobia, ambivalent sexism, right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Social dominance orientation was the only one of the two indicators of conservative ideology to predict voting intentions: for every step increase in social dominance orientation, participants were 1.6 times less likely to be undecided or voting for a third party candidate, and for nearly two times less likely to be voting for Clinton. This pattern would lead one to expect social dominance orientation to significantly predict voting for Trump, but due to the overwhelming strength of Islamophobia in predicting votes for Trump (and possibly also due to the small sample size of Trump voters), social dominance orientation did not come out as a significant predictor of voting for Trump vs. all others.

If the reluctance to vote for Clinton is truly due to ideological beliefs alone (i.e., ‘her beliefs and policies do not align with my own, nor would they if she were a man’), then one would expect to see measures like social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism showing up as significant and powerful predictors of voting for candidates other than Clinton. Instead, the strongest predictor of not voting for Clinton among those also not voting for Trump appears to be ambivalent sexism, calling into question at least some of the claims that voting against Clinton has nothing to do with her gender. Simply put, ambivalent sexism is the strongest predictor of voting for a candidate other than Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election, over and above any ideological differences, or, indeed other forms of prejudice.

- Related article: Did Secretary Clinton lose to a ‘basket of deplorables’? An examination of Islamophobia, homophobia, sexism and conservative ideology in the 2016 US presidential election in Psychology & Sexuality

Featured image credit: kurnmit (Flickr, Public Domain)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2dWA6JT

_________________________________

Karen L. Blair – St. Francis Xavier University

Karen L. Blair – St. Francis Xavier University

Karen L. Blair, PhD., is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Canada, and founder of KLB Research. Dr. Blair studies the role that social support for relationships plays in the development, maintenance and dissolution of relationships, LGBTQ Psychology, and the connections between relationships, social prejudices, and health. www.DrKarenBlair.com

It is now 2024, and this work is still extremely relevant as well as very interesting.