In this year’s Democratic presidential primary, Bernie Sanders ran as a Democrat, despite describing himself as a ‘socialist’. In other countries, Sanders would have run as part of a ‘labor’ party, a political grouping that the US lacks. Barry Eidlin explores why the US does not have such a party, while its neighbor, Canada, does. He writes that in the 1930s, President Roosevelt co-opted labor and workers’ interests into the New Deal coalition; while at the same time, Canadian parties’ repression and neglect for workers’ created an opportunity for a new party to emerge which eventually became the New Democratic Party.

In this year’s Democratic presidential primary, Bernie Sanders ran as a Democrat, despite describing himself as a ‘socialist’. In other countries, Sanders would have run as part of a ‘labor’ party, a political grouping that the US lacks. Barry Eidlin explores why the US does not have such a party, while its neighbor, Canada, does. He writes that in the 1930s, President Roosevelt co-opted labor and workers’ interests into the New Deal coalition; while at the same time, Canadian parties’ repression and neglect for workers’ created an opportunity for a new party to emerge which eventually became the New Democratic Party.

Class and inequality have been front and center in this year’s presidential election. Donald Trump’s message of xenophobia and protectionism has found a receptive audience among parts of the white, male, blue collar segment of the working class, which has been devastated by decades of deindustrialization and deunionization. For her part, despite years building and promoting the policies that have sharpened economic inequality, Hillary Clinton has presented herself as the champion of those left behind by the “new economy,” promising to “get tough” on Wall Street excess, increase educational opportunities through college affordability programs, oppose trade deals she previously supported, and more.

Both have been responding to voters’ sense of economic frustration and insecurity, but in Clinton’s case she was also pushed to address these issues by the remarkable challenge she faced from Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT). In an election season full of surprises, one of the biggest was that a rumpled, self-described “democratic socialist” from Vermont gave Clinton a serious run for her money in the Democratic nomination contest.

But for everything surprising about Sanders’ campaign, one thing was entirely predictable: the fact that he ran as a Democrat. Although he toyed with the idea of running as an independent, he concluded that he had little choice but to contest the Democratic nomination.

Sanders had good reason to reach that conclusion. Few countries have as deeply entrenched of a two-party system as the US, and the US remains one of the only industrialized democracies without a well-established labor or socialist party. In almost any other country, Sanders would likely have tried to be the standard-bearer for such a party. But in the US context, that option was unavailable.

This lack of a US labor party might not seem like such a big deal, especially given that such parties in the countries where they do exist today often look indistinguishable from the Democratic Party. But research shows that many of the US’s policy failures, particularly its lack of a public health care system and its skimpy, punitive social benefits, can be chalked up at least in part to the lack of a labor party.

Is a US labor party impossible?

The conventional wisdom holds that American culture and politics make a labor party all but impossible. Going back more than a century, the German sociologist Werner Sombart famously argued that economic prosperity undermined efforts to build a socialist party in the US, which “came to nothing on roast beef and apple pie.” Friedrich Engels noted the obstacles that the US’s “purely bourgeois” culture posed to the formation of a labor party, particularly its lack of a feudal past. Decades later, US social scientists like Louis Hartz and Seymour Martin Lipset built on Engels’ insights, contending that the US’s pure “Lockean” liberalism created exceptionally hostile terrain for a labor party to take root.

On top of its hostile political culture, many have argued that US election rules create insurmountable obstacles for labor parties, or any kind of third party for that matter. According to such accounts, “winner-take-all” elections combined with a presidential (as opposed to parliamentary) political system virtually guarantees a two-party system.

Canada and the US: diverging histories

Historically, it’s true that labor parties have faced an uphill battle in the US. But in new research I show that focusing on enduring traits like political culture and election rules misses a big part of the story: prior to the 1930s, there was a much more vibrant independent left party tradition than exists today.

Things get even trickier when we compare what happened in the US to what happened elsewhere. I compared labor party fortunes in the US with those in Canada, its neighbor to the north. Although both countries are socio-economically similar, Canada differs when it comes to politics: the US famously lacks a labor party, while the New Democratic Party (NDP) is well established in Canada. Compared to the US, scholars have identified the NDP as a key reason for Canada’s relatively lower levels of inequality, stronger labor laws, and more generous social benefits, including its publicly-funded health care system.

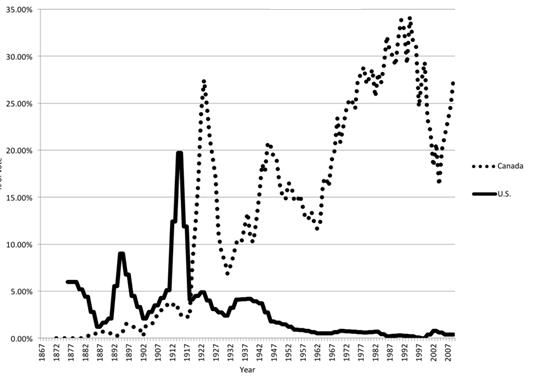

Just as the conventional wisdom holds that a labor party is a virtual impossibility in the US, the existence of a labor party in Canada is generally taken for granted. The standard view is that Canada’s more collectivist political culture and parliamentary political system created favorable terrain for a labor party to take root. But a look at the historical data tells a different story: despite the seemingly more favorable political terrain, Canadian labor and left parties had at least as hard a time getting off the ground as their US counterparts prior to the 1930s. It was only in the 1930s that we saw a divergence.

Figure 1 – Independent Left Third Party Vote Shares, US and Canada 1867-2009

Parties, Politics, and Policy

Why was there such a stark shift in the 1930s? To figure it out, we need to look at how the ruling parties of the time (Democrats in the US, Liberals and Conservatives in Canada) responded to the worker and farmer protests sparked by the Great Depression.

In the US, President Roosevelt and the Democrats adopted a co-optive response that absorbed the protests and undercut political challengers. This involved a combination of rhetorical appeals invoking “the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid,” along with policy reforms that simultaneously drew key farmer and labor constituencies to the Democrats, while creating divisions within those constituencies that undermined independent farmer-labor party efforts.

In retrospect, this might seem obvious. But that’s because we forget what the Democrats and their political coalition looked like in the 1930s. In 1932, much of the party’s leadership was to the right of President Hoover (a Republican), criticizing him not for inaction in the face of the Great Depression, but for wasteful deficit spending. Roosevelt represented the more liberal wing of the party, but even he campaigned as a deficit hawk, and made no mention of labor rights during the campaign. As for labor, it did not yet have the kind of institutional commitment to the Democrats that exists today, and workers’ party allegiances were governed more by neighborhood, ethnic, or religious ties.

Credit: Jim Bowen (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

What changed? First, Roosevelt faced a challenge for the party presidential nomination from former New York Governor, Al Smith, the 1928 nominee. He represented the conservative wing of the party, which was concerned about what they saw as FDR’s class-laden “forgotten man” rhetoric. This made the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s class rhetoric far more of a campaign issue than he and his supporters had hoped. In the general election against Hoover, his contradictory mix of social welfare liberalism, defense of states’ rights, and fiscal austerity won over the electorate, while also creating an opening to bring labor into the Democratic Party tent.

Once in office, FDR’s New Deal policies not only reshaped the economy; they reshaped politics. Agricultural policy, which centered around price subsidies and preventing farm foreclosures, largely benefited wealthy large farmers, while placating family farmers and excluding tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and farmworkers. This consolidated a conservative “farm bloc” within the New Deal coalition, while also drawing small farmers, the backbone for agrarian populism, into the Democratic Party.

As for labor, the perceived benefits of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA, or Wagner Act) drew unions towards Roosevelt, while his increasingly ambitious “Second New Deal” reforms led business elites to abandon him. Deprived of business support, FDR embraced labor as a key source of funds and votes for his 1936 re-election campaign. Enamored of their newfound influence, union leaders who had previously supported a labor party tempered their position.

Just as the Wagner Act drew potential labor party supporters into the Democratic Party, so too did it undermine independent labor party efforts. It did so by pitting the rival American Federation of Labor (AFL) and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) against each other over the Act’s implementation and interpretation. This drew organizational energy away from labor party organizing and sabotaged cross-union political collaboration, particularly at the local level. These divisions solidified the labor–Democrat alliance at a moment in the late 1930s when labor seemed poised to organize for independent class politics. The combination of inter-organizational conflict and resource diversion undermined whatever base might have existed for labor party support. This left the Democrats as the only game in town.

Meanwhile, in Canada…

Comparing the US with Canada highlights how much parties’ political maneuvering and policy offerings mattered for the fate of an independent labor party. There, neither major party grasped the depths of the crisis, and both remained opposed to government intervention in the economy. Their response to farmer and worker protest was not co-optation, but coercion.

Conservative leader R. B. Bennett capitalized on dissatisfaction with incumbent Liberal prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to defeat him in the 1930 election, but his victory was not based on promising to solve the country’s economic problems. Rather, he ran on a law and order platform, vowing to crush farmer and worker protest under an “iron heel of ruthlessness.” Bennett’s failure to revive the economy cost him the election in 1935, which returned King’s Liberals to office. But even then, King did little to reach out to aggrieved workers and farmers, and continued to tamp down protest.

Thus, whereas US New Deal policies absorbed key constituencies into the Democratic Party while undermining independent political organizing, Canadian ruling parties’ policies of repression and neglect of farmers and workers foreclosed the possibility of absorbing them, creating an opening for a new party to emerge: the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) precursor to today’s NDP.

By The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The problem was that Canadian labor remained divided on the question of its political affiliations. Some sought closer ties to the CCF, while others maintained a non-partisan stance. The non-partisans were aided in their efforts to resist CCF affiliation by supporters of the Communist Party.

World War II brought the question of labor’s political affiliations to the fore. Unlike in the United States, where Roosevelt’s wartime labor policy successfully absorbed the labor leadership and tightened the labor-Democratic Party alliance, King’s wartime labor policy further alienated Canadian labor. He excluded labor representatives from wartime planning agencies, and his efforts at promoting collective bargaining were purely advisory and ignored by employers. Meanwhile, he responded to wartime strikes with increased state repression.

Spiraling class conflict spilled into the political arena, as the CCF surged in industrial Ontario with an impressive showing in the 1943 provincial election. By uniting their agrarian Western base and industrial workers in Ontario, the CCF was now a much more serious threat to the Liberals, and a more viable political option for labor. This prompted labor’s non-partisan faction to switch sides, backing a resolution at the 1943 CCL convention recognizing the CCF as the “political arm of labour.” Labor’s commitment to the CCF allowed it to take root as a viable labor party in Canada.

Where’s the Party?

Party systems can seem like immutable facts. It’s easy to think that there can only be a two-party system in the US, or that a multi-party system is obvious for Canada. But a look at the history shows that these systems do change. Political options have narrowed considerably in the US since the 1930s, leaving labor and other progressive constituencies with little choice but to support the Democratic Party, often viewed as the “lesser evil.” Likewise, political options expanded in Canada with the establishment of the CCF, and later the NDP.

These changes were not predetermined by deeply rooted political cultures or electoral rules. Rather, they were the outcome of political struggles during the Great Depression. This is important to keep in mind as party systems in both countries come under increasing strain. In the US, supporters of Bernie Sanders’ “democratic socialist” insurgency may grudgingly vote for Clinton in November, if only out of fear for the Trump alternative. But they remain a powerful reminder of the real demand that exists for a progressive class politics far beyond the tepid Clintonite liberalism currently on offer from the Democrats. Meanwhile, Trump’s candidacy has blown up the Republican Party, with some suggesting that the party might split into separate “alt-right” and “mainstream conservative” parties in the aftermath of the election.

As for Canada, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals are benefiting not only from their leader’s charisma and celebrity status, but also from the fact that opposition parties are in disarray. None (save the Greens) currently has a permanent leader. For its part, the NDP has drifted far from its roots as a progressive tribune, to the point where it found itself outflanked to the left on key issues by the Liberals in last year’s election, and some on the left question whether the party is still worth supporting.

With parties now fracturing in the US and drifting apart in Canada, the systems that initially took shape nearly eighty years ago might be coming to an end. If they do, the fact that they will have lasted so long will testify to how durable political institutions can be. But the fact that they change will serve to remind us that, durable as they might be, those institutions are ultimately the product of human struggles.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Why Is There No Labor Party in the United States?’ in the American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2dmSbE7

_________________________________

Barry Eidlin – McGill University

Barry Eidlin – McGill University

Barry Eidlin is an assistant professor of sociology at McGill University and an affiliate of the Scholars Strategy Network.