Despite the US Constitution’s separation of church and state, American religious institutions and movements are often active in politics. But are they following their congregants’ existing views and actions or influencing them? Using national survey data, Andre P. Audette and Christopher L. Weaver find that churches do engage their congregants politically; at least 50 percent of congregants engage in at least one form of political activity such as attending a rally or registering voters, and a substantial number have also heard sermons addressing political issues such as voting, the Black Lives Matter movement, and abortion.

Despite the US Constitution’s separation of church and state, American religious institutions and movements are often active in politics. But are they following their congregants’ existing views and actions or influencing them? Using national survey data, Andre P. Audette and Christopher L. Weaver find that churches do engage their congregants politically; at least 50 percent of congregants engage in at least one form of political activity such as attending a rally or registering voters, and a substantial number have also heard sermons addressing political issues such as voting, the Black Lives Matter movement, and abortion.

- On 15 June 2021, LSE Religion and Global Society (RGS), together with the US Centre and Department of International Relations, hosted an LSE Public Lecture, Religious Freedom under the Biden Administration. In conjunction with that event, RGS and the US Centre’s USAPP Blog have launched a joint series focusing on religion in American society, bringing in experts to explore the relationship different faith groups have with American society. Read other posts in this series.

Despite the ostensible separation of church and state in the United States under the First Amendment of the Constitution, religious movements have long been quite active in American politics. Over the last few decades, white evangelical Protestants have heavily engaged in political activism in support of conservative causes and candidates. While evangelicals may have first been mobilized around putatively religious social issues, evangelical conservatism now extends to a much broader range of issues, including national security, immigration, and taxation. This even extends to resistance to COVID-19 countermeasures. White evangelical Republicans are even more likely to refuse vaccination than even other Republicans. As an even more extreme example, observers have also noted the number of Christians who participated in the 2021 US Capitol attack.

Less clear, however, is the specific role of churches in this political activity. In the above example of COVID-19 policy attitudes, some churches have made headlines for their resistance to closing, push for reopening, and opposition to preventative measures. Moreover, many congregants and conservative leaders support this resistance. As advocates for COVID-19 countermeasures push for organizations and community leaders to encourage their members to comply, it raises a question about whether churches shape members’ views and actions on politicized issues. Are such churches shepherding their flocks and causing their members to adopt more skeptical stances toward COVID-19 and countermeasures such as vaccines and mask mandates? Alternatively, are the shepherds following their flocks and simply responding to the views of their congregants and adopting policies that they think will attract or keep these members?

How do churches lead their congregants’ political views?

Parsing out the details of this dynamic has been one of the major objects of study in the field of religion and politics. Indeed, we have previously argued that churches may engage in politics at least partially as a way to attract politically-interested congregants within a shrinking religious marketplace. Nevertheless, there is also good reason to believe that churches are actively influencing members’ behavior rather than simply responding to their preferences. Churches have the potential to influence both their congregants’ actions and their views: churches could lead their congregants directly in political action, but they can also inform their congregants’ political views via messaging from the pulpit.

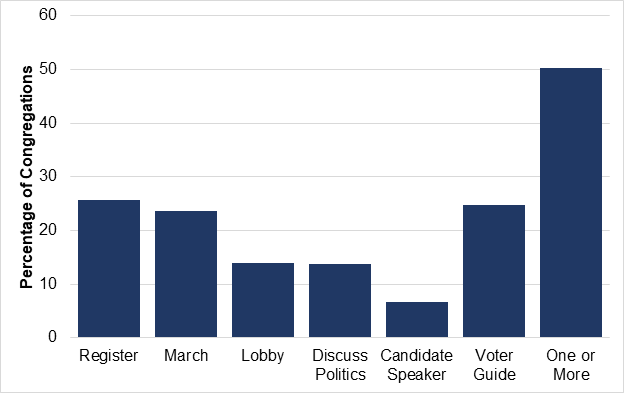

To help explore these questions, we use data drawn from the most recent wave of the National Congregations Study (NCS), which in 2018 surveyed a nationally representative sample of American churches, synagogues, mosques, and other places of worship to collect information on these congregations’ demographics and activities from congregational leaders. A number of these possible activities are political: registering voters, attending a march or rally, lobbying elected officials, organizing groups to discuss politics, hosting a candidate for office as a speaker, and distributing voter guides.

Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on Unsplash

As shown in Figure 1 below, a substantial number of congregations engage in each of these activities, and around 50 percent of all congregations engage in at least one of these activities. Voter registration is the most prevalent form of organized political activity, but nearly as many congregations organize participation in marches and rallies or distribute voter guides to congregants. In this way, churches directly mobilize their congregants to take political action either in or outside of elections. It should be noted that these data were collected in 2018 and therefore may not reflect the higher levels of engagement expected in a presidential election year.

Figure 1 — Frequency of Congregational Political Activities

Small numbers of congregations also reported engaging in other types of political activities. For example, 2.4 percent of congregations said they publicly supported or opposed a candidate for public office. What is more, another 12.8 percent said they would have publicly supported a candidate if it would not put them at a tax risk. With respect to non-electoral political activities, 3.8 percent of congregations declared themselves sanctuaries for undocumented immigrants, and another 10 percent discussed doing this.

Mobilizing congregants from the pulpit

In addition to directly engaging congregants in politics through organized activities, churches can also shape members’ views in ways that either inspire political action or influence the target(s) of that action. The clearest mechanism by which leaders can inform congregants is from the pulpit itself: according to data collected by the Pew Research Center, approximately two-thirds of American church sermons included explicit political messages in the months before the 2020 election. Similarly, Pew data show that congregants are conscious of these messages with a substantial number saying they have heard sermons addressing voting, protesting, the Black Lives Matter movement, abortion, or coronavirus policies. It seems that congregation leaders use the pulpit to convey political messages, and congregants listen.

While a certain amount of self-selection may mean that churches are “preaching to the choir” in the sense that their congregants already agree with congregation leaders’ views, churches also have a meaningful effect on congregants’ political actions and attitudes through a variety of mechanisms. As we discuss above, this can include direct mobilization through organized activities or messaging through sermons. As such, it seems that churches have opportunities to shape whether and how their congregants engage in politics, and in turn these churches may also bear some responsibility for the actions of their adherents. In the data referenced above, it is perhaps notable that 31 percent of evangelical church attendees heard sermons that opposed COVID-19 related restrictions, whereas only 7 percent of evangelical Republicans heard their clergy speak out about the 2021 US Capitol attack. All this points toward the conclusion that churches are indeed politicized spaces and that conversations about politics and policy should involve consideration of the role of churches as political actors.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/39Wbvmk

About the authors

Andre P. Audette – Monmouth College

Andre P. Audette – Monmouth College

Andre P. Audette is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Monmouth College. He researches and teaches courses about religion and politics, law, identity politics, and political behaviour.

Christopher L. Weaver – Northeastern State University

Christopher L. Weaver – Northeastern State University

Christopher L. Weaver is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Northeastern State University. His research and teaching focus on American political behaviour and identity politics. He is particularly interested in how identity and belief affect political behavior and public opinion, especially among religious groups and marginalized groups.