The 2016 election campaign and the seemingly authoritarian tendencies of President Donald Trump to have led many to raise the specter of the rise of an American form of fascism. Ewan McGaughey argues that Trump is what he terms, “fascism-lite”, and has made what has been generally implicit in Republican and Supreme Court politics up to now – high levels of corporate influence, and a general disdain for democracy and social justice – explicit.

The 2016 election campaign and the seemingly authoritarian tendencies of President Donald Trump to have led many to raise the specter of the rise of an American form of fascism. Ewan McGaughey argues that Trump is what he terms, “fascism-lite”, and has made what has been generally implicit in Republican and Supreme Court politics up to now – high levels of corporate influence, and a general disdain for democracy and social justice – explicit.

Media outlets have repeatedly discussed whether President Donald Trump is a fascist. The truth is, today’s politics are consistent with Republican Supreme Court politics over the last 40 years. Authoritarian and obsessed with corporate power, yes, but lacking a key element of concern for insider-welfare displayed by fascist parties of the 1920s and 1930s. Unhinged, but weak, Donald is fascism-lite. He just makes what was implicit explicit.

An attack on American Democracy

The 2016 election epitomises the long-term breakdown in American democracy. Even aside from Russian cyber-war and hate rallies, it cost $6.9 billion. This can all be traced back to a plan by a corporate lawyer, Lewis Powell, in 1971. Faced with progressive success through the 1960s, Powell wrote a memo for the US Chamber of Commerce: ‘Attack on American Free Enterprise System’. It said corporate executives must start to ‘press vigorously in all political arenas for support of the enterprise system’.

It is time for American business — which has demonstrated the greatest capacity in all history to produce and to influence consumer decisions — to apply their great talents vigorously to the preservation of the system itself.

According to Powell, there were three main problems for ‘the system’: (1) public education, (2) journalism, (3) the courts. President Richard Nixon appointed Powell to the Supreme Court in 1972.

In 1976 the first and decisive change took place. Buckley v Valeo, over powerful dissent, held that candidates could spend unlimited money on their own political campaigns. The Supreme Court majority said the First Amendment’s protection of ‘free speech’ includes ‘spending money’. That supposedly made the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 §608, which limited expenditure (rather than donations) ‘unconstitutional’. Trump, of course, often proclaimed he was self-funding his Republican primary. Buckley was the first Trump-for-President case.

Along with other Republican Supreme Court justices, Justice Powell entrenched hard-line ‘free enterprise’ jurisprudence. In 1978, a 5 to 4 majority in First National Bank of Boston v Bellotti held Massachusetts could not restrict corporate spending during a ballot. These cases made the US different to every democratic country. All democracies place limits on election expenditures (usually by a monetary figure, or through advert limits) to try and ensure that ‘one person one vote’ is informed by equality in deliberation.

We have good international data showing that the least democratic countries spend the most money in elections. After Buckley and Bellotti, the voice of the rich and corporate interests could drown out others in scarce media resources. The Supreme Court sent American politics down the road to serfdom: politicians indentured to business, policies completely at odds with the will of the people.

Forcing Free Enterprise

The Supreme Court did not stop there. ‘Free enterprise’ has achieved a long list of 5 to 4 court judgments since 1979. They took away federal rights of teachers to organize unions at religious schools. They allowed employees to be searched at work, like criminal suspects. They removed the fundamental freedom to organize a union for undocumented workers. They tried to ensure that discrimination claims could not be brought when most employers in the market discriminated (though this was reversed by a briefly functioning Congress). They held votes people cast in Florida could not be recounted, giving George W. Bush the Presidency. They struck down protection against disenfranchising voters in southern states, established for 48 years. No modern judiciary has engaged in a more sustained assault on democracy and human rights.

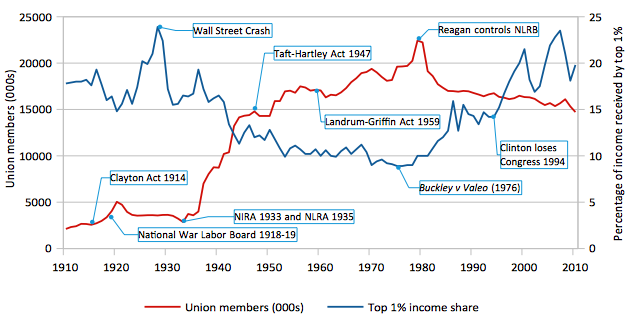

This degradation of voice in politics, the workplace, and the economy occurred at the same time as soaring inequality (making growth irrelevant for most people) as Figure 1 shows:

Figure 1 – US union membership and income inequality

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Series D 940-945, Piketty (2014) Technical Appendices, Table S9.2

The Concepcion era

But the most astonishing phase of case law, still with 5 to 4 decisions in a Republican Court, began with Citizens United v FEC in 2010. It held corporations could spend unlimited money supporting a political cause, including simply damaging (rather than supporting) a political candidate. Justice Antonin Scalia reasoned people in a corporation – employees and shareholders – are all like a political party. Apparently his understanding of political parties was that people are:

giving the leadership of the party the right to speak on their behalf. The association of individuals in a business corporation is no different—or at least it cannot be denied the right to speak on the simplistic ground that it is not “an individual American.

Do people, according to the Republican Court, have any rights they are not ‘giving the leadership’ of a social organisation? AT&T Mobility LLC v Concepcion held that any contract can transfer statutory rights to binding arbitration, without review by a public court. All these contracts, between real people and corporations, are ‘take it or leave it’. With arbitrators selected by big business and big employers, there is no fair and impartial hearing. Apparently, this included all consumer and employment rights. In the old Lochner era social and economic rights were declared ‘void’ by courts. Now, instead, the whole bill of social and economic rights is up ‘for sale’. In this Concepcion era, there are no true rights for anyone, except the enterprise ‘leader’.

Fascist legal theory

Do fascist laws in the 1930s resemble American jurisprudence? Only in part. Otto Kahn-Freund, a Berlin Labour Court judge who was forced to escape, probably produced the most important analysis in 1931. He argued the Weimar Labour Courts had already adopted fascist theory, like Mussolini’s Labour Code, in the late 1920s. Fascism was a political hybrid. Like liberalism it favored private ownership and (superficially) disliked the state. Like social-conservativism it embraced protection of welfare for insiders (but not outsiders). Like collectivism it saw associations as key to total class conflict (the leader always wins). But it would be wrong to ‘overestimate[…] the political self-awareness of the judges.’ Fascism was a subconscious culture.

The most influential fascist corporate lawyer was Dr Johannes Zahn, a visiting scholar to Harvard and researcher for the German banking industry. He wrote the German Public Companies Act 1937, placing banks in charge of most shareholder voting rights, ensuring directors were insulated from accountability, and eliminating any meaningful voice for investors (a voice for workers was obviously repugnant). Zahn was like the Dr Strangelove of corporate law. His goal was to remake the economy so ‘democracy of capital will vanish just as it did in politics.’ And the comic nonsense went on:

When a genuine leader-follower relationship develops between the board and the shareholders, the voting rights of shareholders will lose all practical meaning. In the first place, the shareholder will have much less to say than before. He will not, however, regard himself as a victim because he will trust the leadership.

By comparison, the culmination of Buckley to the Concepcion era, is threefold: (1) the leadership in an association must always win any conflict, as in the reasoning for Citizens United, (2) no state interference to create rights in ‘private’ enterprise, as in Concepcion, and (3) even ‘public’ rights are subordinate to the corporate leader’s will, as in Hobby Lobby. This means there is a difference to fascism: a theoretical concern for insider welfare is missing. As in Hobby Lobby, rights depend on the leader’s discretion. Not fascism, but fascism-lite. This change was not sudden, as UK Supreme Court judge Lord Sumption explains:

The process by which democracies decline is more subtle…. usually more mundane and insidious…. they are slowly drained of what makes them democratic, by a gradual process of internal decay and mounting indifference, until one suddenly notices that they have become something different.

‘… something different…’

That ‘something different’ was Donald Trump. He arrived as it paid politically to make the implicit explicit. Hard-line managerialism defines his persona. He ‘wins’. He says he will ‘make America great again’. He will say to people in his way, ‘you’re fired’. The leader says ‘I am your voice.’ But Donald cannot be characterised as a fascist, because he is embedded in modern Republican power. There is no concern for insider welfare. There is talk of ‘jobs’, but no commitment to full employment. There are pledges to cut the minimum wage. Despite criticizing bad trade deals, there is no commitment to put labor, let alone environmental, standards in them. Not fascist, Donald is fascist-lite.

The strongman image is consistent with a fascist leader, but also an indistinctive Hobbesian monarch who (contrary to 17th century thought) makes everyone else’s lives nasty, brutish and short. Donald says to combat military enemies ‘you have to take out their families’. He pledges to do ‘a hell of a lot worse than water-boarding’. He says there ‘has to be some form of punishment’ for women who have abortions. He promised a mass ‘deportation force’ against 11 million undocumented migrants. Under the US constitution this means inhumane and degrading treatment, infringing the right to privacy, and breaching due process of law. This is not new: the same goals, minimizing torture, abolishing women’s autonomy, total aggression toward rights for outsiders, were consistently propounded by Justice Scalia. Donald just makes the implicit explicit.

Why would anyone have believed Donald would ‘make America great’, when policies are unrelated to the goal? The answer is, the ‘leader’ plays on systemic corruption. The idea that ‘America doesn’t win anymore’ contains an element of truth. Texas Republican Senator Ted Cruz helped shut down government, again, in 2013. Gridlock has meant that Federal legislation to reflect the people’s will has only been possible in four years since 1980 (Clinton and Obama had two each), when Republicans had not throttled Congress. Then there is linguistic propaganda: inheritance tax becomes ‘death tax’. Drilling and fracking become ‘energy exploration’. Employers, who bark ‘you’re fired’, became ‘job creators’. Language becomes, in Newt Gingrich’s words, ‘A Key Mechanism of Control’.

When propaganda does not work there is division: citizens are turned against immigrants. Christians against Muslims. Workers against unemployed. Men against women. Women against their own children. The politics of division is not accidental. It is meant to inhibit people’s sense of solidarity, the basis for taking collective action. The goal is to take people’s trust, and abuse it by making them vote against their own interests. It is the essential strategy of an interest group that cannot win any other way. When all else fails, they lie and steal the vote. This political reality entitles every person, every institution, especially courts, to resist. Sometimes, just sometimes, we must ‘let justice be done, whatever be the consequence.’

Democracy and social justice

Though American politics may appear dangerous ‘democracy and social justice’, to make a ‘living law’, is far stronger. It is no historical accident that half the Amendments to the US constitution since 1789 extended democracy, from votes for people once classed as property, for people who had no property, for women, for young people, for all. The central question is how to undo the interest groups that produced the Powell memo, Buckley v Valeo and Donald Trump. Long-term political shifts are not about winning elections, but altering the underlying forces of social power. Politics reflects this. The key will be completing democracy in politics and extending democracy in all social organization: that means (1) votes at work, (2) votes in the economy, and to support the people’s voice (3) an end to wealth discrimination in all education.

The fact that a mendacious coward like Donald captured the presidency was not unpredictable, but is evidence that something was deeply wrong. Donald is a deeply troubled and insecure individual, just more evidence that money alone does not make you happy. The politics too are driven by money: the Grand Old Party has become a wholly owned subsidiary of corporate interests and the Democrats have struggled to resist arrest. Democratic and civil society, with the silenced majority in America, will need to contain this Republican regime. This is the real, and necessary, “wall”. A new dark age in the United States of America could be looming, but the case for social transformation is compelling, and greater.

*This article is based on a longer piece, originally released in May 2016, in Ewan McGaughey, ‘Fascism-lite in America (or the Social Ideal of Donald Trump’ (2016) TLI Think! Paper 26/2016

Featured image credit: By Gage Skidmore from Peoria, AZ, United States of America (Donald Trump) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2lD9Que

_________________________________

Ewan McGaughey – King’s College, London

Ewan McGaughey – King’s College, London

Dr Ewan McGaughey joined King’s as a lecturer in 2014, and is a Research Associate at the Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge. He was a visiting scholar at the Center for the Study of Law and Society, UC Berkeley in 2016, holds degrees from King’s, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin and the London School of Economics, and has taught at UCL. His core research interests are economic and social rights, and the governance of enterprises.

“Media outlets have repeatedly discussed whether President Donald Trump is a fascist.” Yes: CNN, NBC, ABC, CBS, NY Times, Washington Post; all are extensions of the Obama/Clinton campaigns and any other globalist Left-wing cause. They are as “impartial” as the lugenpresse in 1930s Germany when they wrote about their enemies. These so-called media outlets espouse their opinions as if they are fact, and they are quashing opposition with vile labels such as “hate”, “bigot”, “racist”, “Islamaphobe”, “nazi”, “bigot”, “fascist” (and now, “fascist-lite”). This is how the media and academia force their views upon other people by threatening to give someone such a label. This is the modern-day version of censorship and thought-police. But unlike censorship of yester-year, today they use the smiling faces of members of the media and Hollywood, for which this essentially normalizes censorship and thought-control by using celebrities.

“We” as a society have done a political 180. It was Liberals that used to “push the envelope” by doing anything they could to offend the Conservative establishment by any means necessary; but now that the Liberals dominate the media, Hollywood, and academia, it is now them who do not want to be offended, and they fight back with threats of economically ruining their opponents lives with such vile labels.

As far as the campaign spending in the 2016 election, Hillary raised and spent much more money than Trump. So perhaps the portion of this article that relates to campaign money should be focused on Hillary instead of Trump.

I do not agree with McGaughey that Trump is “fascism-lite”. Hitler & Goebbels & Goering all were considered clowns, too, by the clever-classes in the 1920s — and those 3, too, did an excellent job of fitting-in with existing European practices & policies & biases, back then,the Nazis got elected on platforms which seemed-familiar, but once-in-power the actual policies they pursued were _so_ different… formerly-clever & dismissive Europeans were “shocked, shocked”…

Same here. Trump, I believe, is simply an opportunist demagogue — saying anything to get elected, doing things very differently once in-power — “winging-it”, in the phrase en américain, while he gives-in to his own worst fears and personal insecurities. He is not a Republican — the GOP was long-dead, slain by Sara Palin, abandoned by its own leadership, Trump purchased the remnants to help him in his Quest, not incidentally at fire-sale prices & as-usual he stiffed the sellers — now he is, instead, an Employer, who maintains “staff” in his Cabinet and Congress whom he is pleased to “fire” as-needed or arbitrarily per whim, just as he did on his infamous television show. This is personal and not policy: Hitler did it, Napoleon did it, many a Roman emperor tried to and a few of them succeeded as well — it is the classical posture, for any opportunist demagogue who, like Trump, arrives to power as much to his own surprise as to the surprise of others. It is ad hoc rule.

So McGaughey’s analysis here is beside-the-point, I think, although it is very interesting. Republican and particularly Supreme Court politics have been very distressing recently, yes: Citizens United, and Mr. Justice Scalia on democracy & social justice & strict-constitutional-constructivism, yes. There Trump just makes what has been implicit for 40 years explicit, yes.

There has been a “long-term breakdown in American democracy” here, too: Lewis Powell was upsetting, campaign-money has been, Free Enterprise has been made in fact non-Free, and yes “the degradation of voice” — excellent point — has been a fundamental change from all that has gone before in US politics, true and well-worthy of many books and deep debates, now.

“Fascist legal theory”, as well, has enjoyed a fascinating survival in spite of the spectacular and horrendous failure of Fascist “political” theory, during the initial half of the Terrible Twentieth — together with “Communist political theory”, although what that system had for “law” has dwindled — the two systems shared a totalitarian aspect which condemned and destroyed them both, so the survival of Fascist law, at least of its theory, was somewhat mysterious… Hannah Arendt had things to say about totalitarianism and its universality which somehow the lawyers just sidestepped, perhaps.

But all that is correlation without causation — it misses, and excuses, the even more dangerous political dynamic which has taken place here. Trump is not the “something different” identified by these other deep-trends — not the unpredictable “rough beast slouching toward Bethlehem” they predicted and needed. He is, instead, something far older and IMO far worse: he is the demagogue — the unprincipled tyrant, able to manipulate the unhappy mob, who does not know and does not care what he will do once he ascends to power and “wins”.

All those other things are driven by “reasons” — and reasons can be parsed, broken-down & analyzed & argued, and opponents then can persuade, reasonably. What we have now though is not that, but harsh, un-reasoning, arbitrary-power — arbitrary, meaning that it cannot be arbitrated, understood, discussed and debated, it simply is sovereign-will, a very old idea supported simply by armed might and which preceded all forms of government, democratic and other — and ironically the tyranny of arbitrary-power will follow democracy, in the classical formulation, and that in Trump is what the USA has now.

It would be nice if he would give reasons for his views… Explanations would be useful, too… But the USA’s new President is not good at either of these, and the medium he uses to express himself does not really permit it — how many reasons and explanation can be fit into 140 characters?…

So the US has a fundamental problem, now, un-reasoned tyranny — that is one deeper than fascism, deeper than democracy, and far older than all social systems — it was the reason the Roman Republic was founded, the origin of the Greek city-states, the later origin of most recoveries from times-of-troubles when all was lost and societies had to begin again. An unprincipled demagogue controlling the demos is a primal thing — the primal fear of Plato, and of so many other thinkers in politics — and in the US we are back to this again… in 1776 we rebelled against it, ultimately-successfully, but now we are back to it again…

There are things that can be done. Trump may not last, and the 25th Amendment is prepared & waiting… And Trump may change, although that vain hope now nearly is extinguished, among the wishful-thinkers who watched him so carefully just after his election, to see whether he “really” would do all those strange things he’d been preaching during his Campaign… only, well, now he is doing them…

But this has been a sea-change, for US politics — not an inevitable result of reasons which now may be dissected themselves for analysis and remediation — this is a return to a primal politics we have not seen since before our Constitution, since before even our primitive Articles of Confederation… a tyrant exercising arbitrary power… that goes a long way back, for most Americans…

The mystery to be solved now is, why did nearly-half of us do this? The Other Half — the Democrats — arrogantly & ignorantly neglected those folks, and the Democratic leadership are very much to be blamed for that omission and under-estimation, they need to examine the Midwest and the South, now, very closely, and somehow fold those enormous regions and populations back into our national politics. A new Opposition Party replacing the tired and spent old GOP might help; a completely reorganized and younger Democratic Party might be more aware and better-informed and less-“entitled”, next time; in all cases the focus must be, this time, less on party-unity than on the people left-out — we are split 50-50 now, the last time was just before our most-terrible Civil War, and that is very dangerous.

But history hasn’t led us here, there is nothing “historically-inevitable” about it. The System still works and contains good tools — including the Electoral College, designed as was the Senate too, by our Founders to keep us together, and it has served both sides well in such conflicts. But no, the issue here is not fascism, or campaign-money, or The Court, or now Trump, or any other partial-remedy amenable to easy fixing — instead, “The problem is US,” as Pogo put it.