Wars divert public attention to foreign affairs. While this provides the president with leverage in his encounters with Congress, public perception of the war can turn the tide against him. Research by Susanne Schorpp and Charles Finocchiaro shows that the president’s gains from public attention to foreign affairs are mediated by the human cost of war. As casualties increase, the public’s position will shift from support to blame, allowing Members of Congress to oppose the president.

Wars divert public attention to foreign affairs. While this provides the president with leverage in his encounters with Congress, public perception of the war can turn the tide against him. Research by Susanne Schorpp and Charles Finocchiaro shows that the president’s gains from public attention to foreign affairs are mediated by the human cost of war. As casualties increase, the public’s position will shift from support to blame, allowing Members of Congress to oppose the president.

When Dustin Hoffman and Robert De Niro’s characters in “Wag the Dog” invent a war to save an embattled president’s reelection chances, they build on the popular adage that wars benefit presidents politically. While the movie is clearly a satire, such “diversionary wars” are a topic of debate in political science that has gained new momentum in the Trump era. Empirical evidence backs up the general consensus among scholars that wars are, indeed, good for presidents. They can increase presidential approval (consider the rally round the flag phenomenon), raise the president’s chances of winning in court, and bring congressional policy closer to the president’s favored position.

At the same time, research on public opinion also teaches us that the human cost of war can have negative consequences for elected officials. Rising casualties can decrease presidential approval and reduce the reelection prospects of incumbents.

We offer an explanation of when and how these two opposite forces influence the president’s bargaining power with Congress. While wars can benefit presidents, we argue that executive advantage depends on the salience and severity of the conflict: When the public perceives the war as a salient issue (i.e., their focus is diverted from domestic issues to defense and foreign policy issues) they will be sensitive to the human costs of war. While the war is progressing as expected, presidential leverage will rise. As casualties mount, however, the tide is likely to turn.

Salience matters, because, as Neustadt famously declared, the president’s power is the power to persuade. The president’s powers of persuasion are particularly high in matters of national security, where they holds an informational advantage against the legislature. In matters of national security, the public looks to the executive for leadership, placing pressure on members of Congress to support the president.

Once the public’s focus is directed at foreign affairs, though, such attention can be either a blessing or a curse for the president. As long as the costs of war remain within expected parameters, the public will remain deferential to presidential leadership. As the severity of war increases, they may turn to the president to place blame. That, in turn, makes it much easier for members of Congress to oppose the president’s position.

The contrasting reelection bids of George H.W. Bush and his son George W. Bush offer an illustrative example. While the Persian Gulf War was popular and remained well within expected casualty levels, by the time George H.W. Bush was up for reelection, the public had moved on to domestic concerns. He lost the presidency to Bill Clinton. When his son sought reelection twelve years later, the country was still enmeshed in the War on Terror. Though public attention had not been consistently centered on the war after 9/11, it remained the primary focus from 2004 until 2008, when the economy supplanted war concerns as the “Most Important Problem” of the nation. Some observers note that George W. Bush benefitted from the public’s preoccupation with war. Though casualties had begun to rise by 2004, it was not until 2006, when Bush lost his majority in both houses of Congress, that the war had become a political liability.

To look empirically at the interactive mechanism of salience and severity of war, we analyzed 50 years of congressional roll call votes to capture variability in support for the president’s favored position over time. To identify votes that were cast in periods when the public likely focused on war concerns (salience), we relied on the Gallup survey’s “Most Important Problem” (MIP) indicator to gauge those instances in which defense and foreign policy predominated. Our representation of severity captures deviation in the casualty rate at the moment of measurement relative to an earlier baseline—measured as the percent change of daily U.S. battle deaths compared to the beginning of the war.

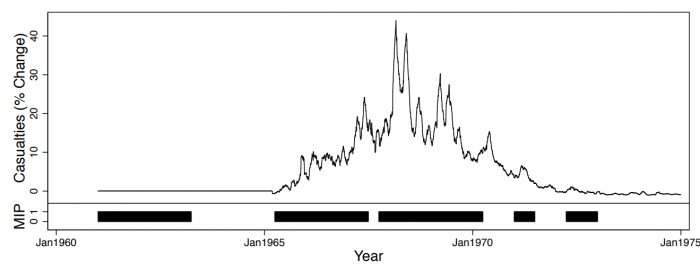

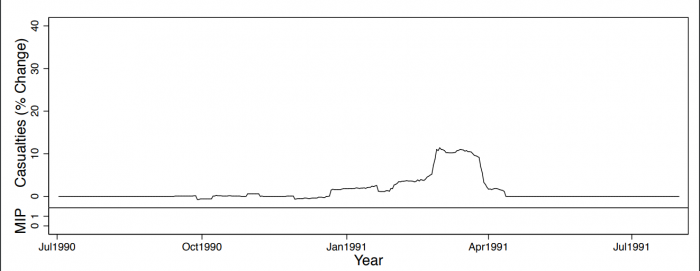

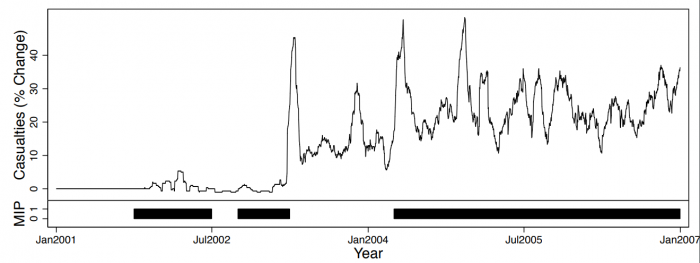

Figure 1. Casualties and “Most Important Problem”

A Vietnam War

B Persian Gulf War

C War on Terror

Note. Trendlines for the percent change in U.S. American casualties incurred for the three wars in our data set compared with the beginning of the war. Black stretches underneath the time series denote periods during which the American public identified a defense or national security issue as the “Most Important Problem” facing the nation. MIP = Most Important Problem.

Figure 1 traces our casualty measure across the three wars included in our dataset. The black boxes under the casualties line indicate times in which war concerns were salient (MIP is a defense or foreign policy issue). As the figure makes clear, the public’s prioritization of the war as a concern and the casualty rate vary quite a bit across and within the Vietnam, Gulf, and post-9/11 conflicts.

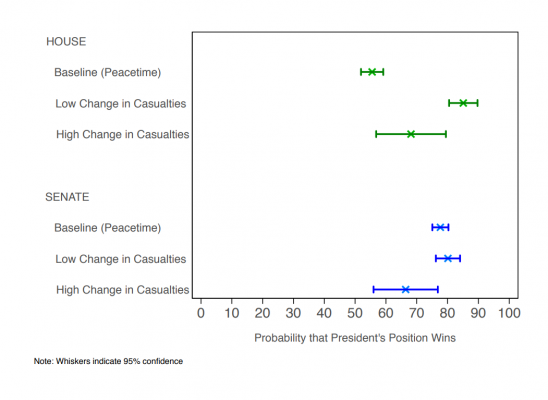

Figure 2. Effect of War on Likelihood of Presidential Success

Figure 2 plots some of the key results of our analysis: How do salience and severity of the war affect the predicted success rate of the president’s favored position on congressional roll calls? For each chamber, we plot the peacetime prediction first, which offers a useful baseline for comparison. In times of peace, when the public is focused on domestic issues (MIP=domestic issue), the predicted probability of a vote in line with the president’s preferred position is about 56% in the House and almost 78% in the Senate. In times of war, however, and when wars are salient (MIP=defense or foreign policy issues), that probability skyrockets to 85% in the House (though it remains statistically unchanged in the Senate).

At least when it comes to legislation passed in the House, presidents are at an advantage as war is a public concern and while casualties remain low. With growing battle deaths, however, this advantage disappears. The president’s advantage decreases significantly in the House. In the case of the Senate, the president fares considerably worse under such conditions than in times of peace: the success rate drops from 85% to a predicted 66%.

Do wars advantage the executive? Our findings suggest that, given the right circumstances, they can. Circumstances, however, are difficult to control and can change. Few foresaw that the War on Terror would become the longest war in U.S. history. The Vietnam War started as a regional conflict with little U.S. involvement. In both cases, a look at Figure 1 shows that, over the long run, casualties mounted. Thus, looking to the future, one lesson is that the tides of the president’s political fortunes are likely to turn when conflicts drag on with increasing casualties and wavering public support. Unless, of course, the orchestration of the war remains firmly in Dustin Hoffman’s and Robert de Niro’s capable, yet fictional, hands.

This article is based on the paper, “Congress and the President in Times of War” in American Politics Research.

040618-N-0683J-041 by the United States Navy is licensed under Wikimedia Commons.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2guevOk

_________________________________

Susanne Schorpp – Georgia State University

Susanne Schorpp – Georgia State University

Susanne Schorpp is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Georgia State University. Her main area of research is in judicial politics, with a focus on separation of powers, rights protection, and legitimacy. Her research has been published in journals including the Journal of Politics, Justice System Journal, and Journal of Law and Courts.

Charles J. Finocchiaro – University of Oklahoma

Charles J. Finocchiaro – University of Oklahoma

Charles Finocchiaro is Associate Professor in the Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center and the Department of Political Science at the University of Oklahoma. His research spans the field of American politics, with a particular focus on the development and organization of American political institutions and congressional elections. He is currently working on a book project and a series of papers that examine the transformation of the U.S. Congress during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work appears in outlets including the American Journal of Political Science, Legislative Studies Quarterly, and Political Research Quarterly.