Hurricanes like Harvey and Katrina can have a devastating cost for those affected. But how much of this cost is financial? In new research which examines the impact of Hurricane Katrina, Justin Gallagher finds that the total debts of those worst affected by flooding fell compared to those who were not flooded, largely due to a reduction in mortgage debt. In light of this, he writes that flood insurance, government assistance and personal savings will all play an even more important role in people’s financial recovery following future disasters.

Hurricanes like Harvey and Katrina can have a devastating cost for those affected. But how much of this cost is financial? In new research which examines the impact of Hurricane Katrina, Justin Gallagher finds that the total debts of those worst affected by flooding fell compared to those who were not flooded, largely due to a reduction in mortgage debt. In light of this, he writes that flood insurance, government assistance and personal savings will all play an even more important role in people’s financial recovery following future disasters.

As the flood waters in parts of Houston recede, the emphasis for many Hurricane Harvey flood victims will shift from survival to recovery. In recent research coauthored with Daniel Hartley, we provide some of the first victim-level evidence for the financial impact of a costly flood in the United States.

Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey, while the most costly, are just two of many devastating hurricanes to hit the US over the past several decades. Given the overall economic damage of the hurricanes we might expect the financial impact to be large and long-lasting. On the other hand, flood insurance, governmental disaster assistance, non-profit aid, and personal savings could all mitigate the financial loss.

We measured the financial impact from Katrina using credit agency data from a random five percent sample of US residents with a social security number and a credit history. An increase in debt following a flood is one way to manage the unexpected financial shock. However, a spike in the level of debt may be unsustainable, so we also examine rates of bill delinquency, bankruptcy, foreclosure, and changes in credit scores. We focus on the approximately 16,000 people in the sample living in New Orleans at the time of Katrina. While anonymized, we know the Census block of residence and can track each person over time. We divide New Orleans’ residents in our sample into a non-flooded group and four flooded groups using the depth of flooding in their block of residence.

“233646 Alternative Thanksgiving Break, Katrina Rebuilding, Project Homecoming, Day 1-1236” by Alternative Break Program is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

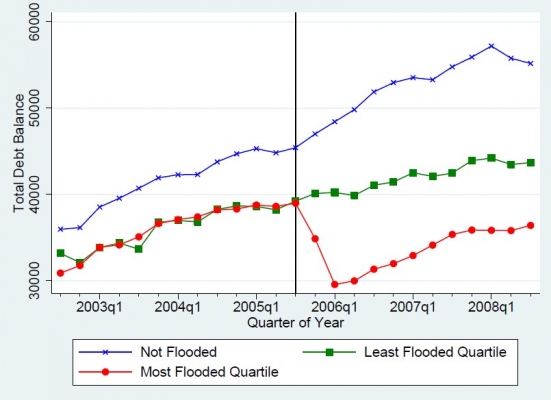

Figure 1 shows total average debt balances in dollars for residents in the non-flooded, least-flooded, and most-flooded groups for the three years before and after Katrina. The vertical line is when Katrina floods New Orleans. There are similar pre-Katrina trends in total debt before Katrina for all three groups. Prior to Katrina, debt levels are nearly the same for those residents who will later experience minor and severe flooding.

Figure 1 – Total average residents’ debt before and after Hurricane Katrina by severity of flooding experienced

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York / Equifax

The figure highlights a key finding. Relative to non-flooded residents, the total debt held by the most flooded residents sharply declines immediately following Katrina. The reduction in total debt is due to lower home loan debt. After controlling for the Corps of Engineers’ pre-Katrina assessed flood risk and the elevation of the property, home loan debt decreases by about $12,000 for the most flooded residents relative to non-flooded residents. This is true regardless of whether we control for other socioeconomic and demographic factors.

The credit agency data indicate, apart from the reduction in home loan debt, that flooding from Katrina had a modest and relatively short-lived negative impact on the personal finance of the most flooded residents. On average, there is a temporary increase of about $500 (15 percent) in credit card debt for the most flooded residents that lasts less than one year. There is no change in auto or student loan debt. Ninety day bill delinquency rates are about ten percent higher for one quarter. Credit scores are about one percent lower for two years.

One limitation of our study is that we do not observe savings or incomes. Nevertheless, our conclusion is also supported by another recent study which uses tax return data to compare flooded New Orleans residents to tax filers with similar financial histories living outside of New Orleans. Tatyana Deryugina and coauthors find, beginning a few years after Katrina, that the incomes for Katrina flood victims surpass those not hit by the flood.

The homeowner decision to use flood insurance to pay down home loan debt accounts for most of the reduction in home loan debt. This makes financial sense for some homeowners. In New Orleans prior to Katrina, the reconstruction cost of a home exceeded the market price for a home in many neighborhoods. A homeowner who faces large rebuilding costs relative to their home value and receives flood insurance may be better off financially by purchasing a similar home in a different neighborhood rather than rebuilding. Any existing mortgage debt would first need to be paid off if the home is collateral for a home loan.

At the same time, if the decision to pay off mortgage debt is due to pressure from the lender, then this is both illegal and probably a poor financial decision for the flooded homeowner. We find evidence consistent with accounts that banks, particularly national banks without a strong local presence, pressured some homeowners to payoff mortgage debt using flood insurance money.

The safety net will continue to be important as hurricanes become more frequent

So what does the experience of Katrina’s victims imply for the financial recovery of those flooded by Harvey?

First, the collective safety net provided by flood insurance, government assistance, non-profit aid, and personal savings helped to promote a relatively quick financial recovery for even the most-flooded victims of Katrina. Flood insurance played a particularly important role. Approximately two-thirds of homeowners in New Orleans had insurance. More than $16 billion was paid out and the average claim was $97,141. The flood insurance coverage rate in Houston is estimated to be much lower at 17 percent. In order for those flooded by Harvey to have a similar financial recovery as the victims of Katrina, per-person direct government assistance to will likely need to be larger.

Second, the Houston metro area has been a region of population growth and increasing property values. Flooded homeowners who have flood insurance are likely to be better off financially if they use the insurance money to rebuild. Residents should be wary of banks that suggest otherwise.

Third, we know that there will be devastating future floods in Houston and elsewhere, and climate change is expected to increase their frequency. The National Flood Insurance Program was created in 1968 to help protect Americans from flooding, while at the same time decreasing the need for direct federal aid following a disaster. Neither objective will be met unless changes to the program are made so that more people who choose to live in areas at greatest risk of flooding are compelled to buy actuarially fair insurance.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2wczzer

_________________________________

About the author

Justin Gallagher – Case Western Reserve University

Justin Gallagher – Case Western Reserve University

Justin Gallagher is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Case Western Reserve University. His primary research field is environmental economics, with a broad interest in applied microeconomics and the fields of labor economics, public economics, and behavioral economics. Gallagher’s research has looked at the value of hazardous waste cleanup, the financial impact on households that experience a natural disaster, and how individuals update their beliefs about environmental risks.