In the 21st century the use of drones has blurred the lines between civilian and military. Joseph Pugliese writes that not only do drone operations increasingly resemble computer games, the location of drone centers within cities like Las Vegas means that their pilots often invoke casino gambling metaphors as they consider their targets.

In the 21st century the use of drones has blurred the lines between civilian and military. Joseph Pugliese writes that not only do drone operations increasingly resemble computer games, the location of drone centers within cities like Las Vegas means that their pilots often invoke casino gambling metaphors as they consider their targets.

Over the last decade, the US government has significantly expanded its military drone program. It has now become an indispensable component in its conduct of wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and Syria. What is unique and disturbing about the US’ contemporary drone wars is the manner in which gaming technologies have now become effectively enmeshed within the operational field of war. Remarking on the crossover between gaming technologies and drone operations, Predator sensor operator, Staff Sgt. Nicolette Sebastian, explains that a drone ‘operation is a lot like Play Station … “Oh, it’s a gamer’s delight.’”

The crossover between computer games and the lethal technologies that enable drone kills is clearly evidenced by the fact that ‘Bored drone pilots sometimes smuggled simple computer games onto the drone operating systems – chess, Solitaire, Battleship.’ The drone console here becomes interchangeable with that of a computer game, as drone pilots upload their own civilian computer games into the same system. A continuum between civilian gaming technologies and lethal military systems is thereby established that signals the increasing gamification of war. The US military, in fact, has modelled the design of drone flight controls on key aspects of computer game technologies: ‘the flight controls for drones over the years have come to resemble video-game controllers, which the military has done to make them more intuitive for a generation of young soldiers raised on games like Gears of War and Killzone.’

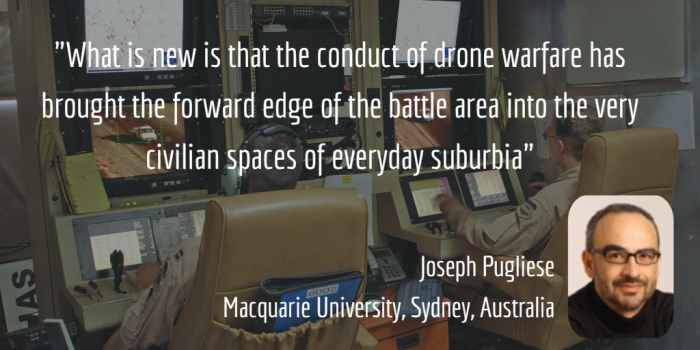

The ensconcing of war operations, and the everyday deployment of lethal drone attacks, within US cities such as Las Vegas, Nevada, shows how the conduct of war has changed. There is nothing unique about the location of military bases within metropolitan cities and civilian centres. What is new is that the conduct of drone warfare has brought the forward edge of the battle area into the very civilian spaces of everyday suburbia. Nellis Air Force Base (AFB), for example, is situated on Las Vegas Boulevard in suburban Las Vegas.

By United States Air Force photo by Master Sergeant Steve Horton (http://www.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123063918 [1]) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Walking through the suburban lots that surround Nellis AFB, I was struck by the juxtaposition of an idyllic simulation of a pastoral setting with a drone base: a family of Bambi-like deer reposing in a suburban front garden face-off the killing apparatus of drones situated across the street behind Nellis AFB’s high-security fence.

In looking closely at this city par excellence of gaming that has a military base inside it, its distinguishing attributes all converge at Nellis AFB, only to become militarily inflected. The pivotal role that gaming plays in the economy and cultural identity of the city, and the make-or-break, do-or-die roles that chance and probability play in its casinos – all find their equivalent at Nellis.

In the context of Nellis’ drone cubicles, the reality of a surveilled village in Afghanistan is rendered as a mere neon-green simulation on the drone pilot’s screen; the honed-skills of video gaming are deployed for the actual drone kills; in fact, some members of US drone squadrons have left positions working in the casino industry and have retrained as drone operators in bases just outside Las Vegas such as Creech AFB. As one drone operator remarks, ‘When I go to work, it’s Game Face On,’ with drone targets referred to as ‘customers’ of this lethal gaming practice. There are, moreover, clear mimetic relations of exchange between Las Vegas’ and Nellis’ gaming consoles, screens and cubicles.

The term ‘drone casino mimesis’ identifies the roles that casino and gaming technologies play in the shaping and mutating of both themselves and the conduct of war. The gaming dimensions – including the role of gambles, chance and probability – are evidenced by the fact that, on innumerable occasions, a named suspect has been reported as having been killed by a drone multiple times and that, in the process, hundreds of innocent civilians, including children, have been killed.

US drone teams call their drone-kill targets ‘bugsplat,’ a term that reduces its human victims to little more than entomological waste. The gaming dimensions of drone kills are evidenced by the words of one former US intelligence official:

You say something like “Show me the Bugsplat.” That’s what we call the probability of a kill estimate when we are doing this final math before the “Go go go” decision. You would actually get a picture of a compound, and there will be something on it that looks like a bugsplat actually with red, yellow, and green: with red being anybody in that spot is dead, yellow stands a chance of being wounded; green we expect no harm to come to individuals where there is green.

Described here is a mélange of paintball and video gaming techniques that is underpinned, in turn, by the probability stakes of casino gaming: as the same drone official concludes, ‘when all those conditions have been met, you may give the order to go ahead and spend the money.’ In the world of drone casino mimesis, when all the gaming conditions have been met, you spend the money, fire your missiles and hope to make a killing. In the parlance of drone operators, if you hit and kill the person you intended to kill ‘that person is called a “jackpot.”’ Evidenced here is the manner in which the vocabulary of casino gaming is now clearly constitutive of the practices of drone kills. In the world of drone casino mimesis, the gambling stakes are high. ‘The position I took,’ says a drone screener, ‘is that every call I make is a gamble, and I’m betting on their life.’

The fatal effects of these ‘bets’ and ‘gambles’ on civilian lives are underscored by a whistleblower, known as ‘the source,’ who remarks that: ‘Anyone caught in the vicinity [of a target] is guilty by association … When a drone strike kills more than one person, there is no guarantee that those persons deserved their fate … So it’s a phenomenal gamble.’ The extraordinary latitude that is inbuilt into these phenomenal drone gambles is demonstrated by the fact that the US military calculates the success rate of its drone kills by focusing exclusively ‘on killing jackpots, and ignores the strategic – and human consequences of killing large numbers of bystanders.’

At play in the US’ drone casino mimesis program is the gamification of war. Drawing on the very words of a number of drone pilots to describe their killing operations, in the conduct of drone telewarfare, as a veritable ‘gamer’s delight,’ the stakes are asymmetrical, the gambles are ‘phenomenal’ and the ‘jackpots’ are, for the targeted civilians of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen, fatal.

This article was based on the paper ‘Drone Casino Mimesis: Telewarfare and Civil Militarisation’ in the Journal of Sociology.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2xoAn4f

_________________________________

About the author

Joseph Pugliese – Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Joseph Pugliese – Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Joseph Pugliese is Research Director of the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. Selected publications include the edited collection Transmediterranean: Diasporas, Histories, Geopolitical Spaces (Peter Lang, 2010) and the monograph Biometrics: Bodies, Technologies, Biopolitics (Routledge, 2010). His most recent book is State Violence and the Execution of Law: Biopolitical Caesurae of Torture, Black Sites, Drones (Routledge, 2013).