The inevitable human complexities of history should not be seen as skeletons in our collective closet. They bring us closer to a real understanding of how we became the people and peoples that we are today, writes Gregorio Alonso.

The inevitable human complexities of history should not be seen as skeletons in our collective closet. They bring us closer to a real understanding of how we became the people and peoples that we are today, writes Gregorio Alonso.

All nations draw legitimacy and status from invented traditions, and Latin American republics are no exception. For over a decade, a host of conferences, exhibitions, ceremonies, and publications have endeavoured to highlight the modern traits and democratic credentials of the nation-states which once were Iberian colonies. These public celebrations honouring the liberators of Latin America are tinged with the usual mixture of victimisation and heroism found in nationalistic narratives that aim to shape ‘public history’. But memory and amnesia are also present in often self-congratulatory efforts to pin down the values, beliefs, and practices ingrained in national souls and psyches.

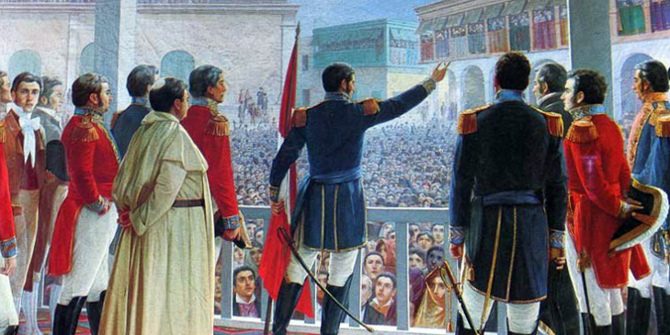

Proclamation of the Independence of Peru (1821), by Juan Lepiani (public domain)

The retrospective identification with an allegedly immemorial national past which permeates most public and historiographic narratives starkly contrasts with the uncertainties and political improvisation that raised new nations from the remnants of the Castilian and Portuguese empires.

Failed attempts at pacification and negotiation with the metropoles, unsuccessful experiments in regional integration, and defeated alternative empires are often dismissed and forgotten. But the idea of a lineal transformation from divisions of empire into truly sovereign nations now finds itself under significant challenge from recent historiography.

To begin with, the relationship between the former colonies and metropoles was never easy. The window of political opportunity for national independence becoming a reality showed how intertwined their respective political fortunes had become. To survive, both Iberian empires have been through rationalisation and reform in the decades predating the decision of the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte to invade the Peninsula in 1807.

The temporary success of the military operations and the sustained resistance against the occupation immediately acquired Atlantic dimensions. Both the Portuguese and Spanish thrones were vacated, with the Portuguese royal family escorted by the British Royal Navy to seek refuge in Brazil, whereas Spain’s Bourbon royals abdicated to Napoleon’s elder brother Joseph in Bayonne.

The colonies radically changed their role as result of these events. Brazil became a haven for Portugal’s royal House of Braganza, with Joao VI keenly aware of his colonial subjects’ interests while ruling the empire remotely until his return to Portugal in 1821. In the Spanish territories, however, the power vacuum engendered by Bourbon complicity with the French resonated across the Atlantic, leading local and regional juntas to claim sovereignty for themselves in the absence of the “kidnapped” king.

Influential Creole families joined forces with representatives of the Crown to exert public authority under these new, harrowing circumstances. After failed British military interventions, two years of uncertainty, and a spreading sense of chaos, in April 1810 the former Viceroyalty of New Granada declared independence as Venezuela. Weeks later, the Southern Provinces of Río de la Plata followed suit, their blood, gold, and political acumen eventually managing to consolidate the country that would become Argentina. In the cases of Mexico, Bolivia, and Perú, it would prove to take even longer, with protracted civil wars, to reach the same endpoint. Spanish possessions in the Caribbean, meanwhile, stayed loyal to the Crown.

This drawn-out and highly conflictual independence process ultimately gave birth to 15 new republics of various sizes, ethnic compositions, and political outlooks. Despite a common period of violent instability and vengeful struggle, Chile and Uruguay fared comparatively once independence was achieved. In contrast, Colombia, Mexico, and Perú were torn apart by seemingly endless social turmoil and political strife.

National and international historians have of late acknowledged these varied experiences and outcomes, presenting a more complex and somewhat less nationalistic picture of the independence struggles.

The case of Pedro Camejo, the Venezuelan former slave better known as Negro Primero who fought for royalists and rebels alike, speaks to the true complexity of Latin America’s wars of independence (Yoelsr1, CC BY-SA 3.0)

There has been welcome recognition of the long-neglected role of native peoples and Afro-descendants on both the Republican and the Loyalist sides of the wars of independence. It has been demonstrated that the seeds of Criollo patriotism were sown by late colonial calls for regeneration.

Pre-existing legal institutions and professions also cast a long shadow on the structural configurations of new republics, many of which endured for decades without significant transformation. Likewise the manifold bonds linking the economies, cultures, and politics of Mexico and the US, which had so often been hidden by the nationalising historiographies of most modern nations.

Most importantly of all, it is now clear that the liberal discourses of many newly independent states was the unintended consequence rather than the cause of their break with the metropole.

The past, then, is not a place of simple retelling but a battleground where opposing narratives aspire to hegemony. It is a place that is all too human and as such holds many surprises.

In 2010 authorities in Mexico City decided to reinter the remains of 12 of the country’s most important independence leaders to commemorate the bicentenary. Much to the dismay of President Felipe Calderón, scientists from the National Institute of Archaeology and History discovered that amongst the heroes’ bones were those of women, children, and even animals, along with remains of an extra two male adults.

As Latin America celebrates the bicentenary of its independence, surely it is time to recognise that rather than being “skeletons in the closet”, these inevitable human complexities bring us closer to a real understanding of how we came to be the people and peoples that we are today.

This article originally appeared at the LSE’s Latin America and Carribean blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2k841WE

_________________________________

About the author

Gregorio Alonso – University of Leeds

Gregorio Alonso – University of Leeds

Dr Gregorio Alonso is Lecturer in Spanish History for the School of Languages, Cultures, and Societies at the University of Leeds. His research ranges from the study of political and religious conflicts in Modern Europe and Latin America to the making of the liberal and the Catholic traditions during the nineteenth Century. He is interested in the political, cultural and religious aspects of Modernity in comparative perspective. His is the author of La nación en capilla: Ciudadanía Católica y cuestión religiosa en España (Comares: 2014) and co-editor of Londres y el Liberalismo Hispánico (Iberoamericana/Vervuert: 2011). He is currently working on a monograph on the European experiences and contacts of the Latin American Libertadores before, during, and after the independence process.

1 Comments