One of Donald Trump’s earliest claims as President was that millions voted illegally in the 2016 election. Given that research has found that voter fraud in the US is exceptionally rare, how can many Americans’ concerns about illegal voting be explained? In new research, Adriano Udani and David Kimball find that anti-immigrant attitudes – especially towards Mexicans – strongly predict beliefs about voter fraud. In light of these findings, they argue that heightened concerns about voter fraud, and public support for Trump’s Commission on Election Integrity, appear to be nourished by a reservoir of hostility toward groups that are politically constructed as “un-American”.

One of Donald Trump’s earliest claims as President was that millions voted illegally in the 2016 election. Given that research has found that voter fraud in the US is exceptionally rare, how can many Americans’ concerns about illegal voting be explained? In new research, Adriano Udani and David Kimball find that anti-immigrant attitudes – especially towards Mexicans – strongly predict beliefs about voter fraud. In light of these findings, they argue that heightened concerns about voter fraud, and public support for Trump’s Commission on Election Integrity, appear to be nourished by a reservoir of hostility toward groups that are politically constructed as “un-American”.

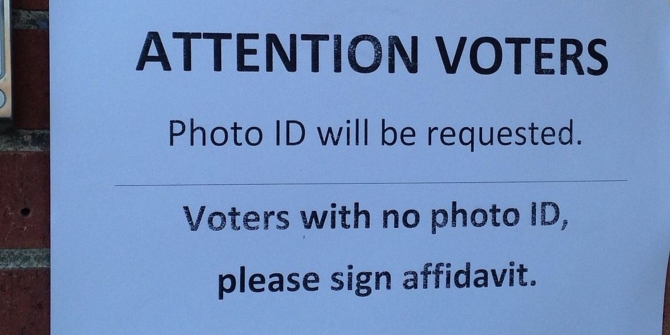

In May 2017, President Trump signed an executive order to establish a Bipartisan Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity to investigate his unsubstantiated claim that millions of people illegally voted in the 2016 election. Since its inception, the commission has received increasing scrutiny and skepticism over its intent to suppress voters, commission membership, and authority. Most recently, the watchdog group United to Protect Democracy (comprised of many Obama administration alumni) filed a lawsuit to keep the Trump administration accountable for the reasons and process that it seeks sensitive personal data on every registered US voter.

As the Commission and its leadership continue to be hotly debated, and more peer-reviewed studies convincingly show that voter fraud is extremely rare and difficult to prove (here, here, here, and here), it is important to understand the public sentiment that fuels and sustains the commission’s hunt for fraudulent voters.

In my recent research with David Kimball, we find a large proportion of American voters with more anti-immigrant attitudes also believe that voter fraud occurs frequently in US elections. Anti-immigrant attitudes strongly predict beliefs about voter fraud and pessimism toward election integrity, often outperforming conventional political predispositions and contextual measures.

Theory suggests that two conditions in the United States have produced a strong association between anti-immigrant attitudes and public beliefs about voter fraud: (a) relatively high levels of immigration in recent years that make immigration an important national issue and (b) a narrative in political rhetoric that frames immigrants as criminals and undeserving of the rights of citizenship. While we test this theory on the United States, we believe that anti-immigrant attitudes are a potent predictor of voter fraud beliefs in other countries where these conditions also exist.

Animosity toward Mexican Immigrants

We first conducted a national survey of 1,000 adult Americans through the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), in which we measure people’s estimates of how often voter fraud occurs (which we and others have conceptualized as noncitizen voting; voting more than once; and, pretending to be someone else). All respondents were asked to use a thermometer rating to indicate how cold (0) or warm (100) they feel about Irish immigrants, which serves as a useful baseline against which to compare the effects of the other immigrant groups. We then randomly assign respondents to one of three group thermometer rating questions on African, Chinese, and Mexican immigrants.

We find that feelings toward Irish immigrants are unrelated to beliefs about voter fraud. In contrast, when asked about the other immigrant groups, people with colder feelings toward those groups are more inclined to think that voter fraud occurs very frequently. Coldness toward Mexican immigrants is associated with an increase in voter fraud perceptions. However, there is no statistically significant relationship between views toward Irish, African, or Chinese immigrants and beliefs about voter fraud. Additional tests of the treatment effects indicate that the Mexican immigrant treatment group had significantly higher voter fraud beliefs than the Chinese immigrant treatment group. No significant differences were found between Mexican and African immigrant groups or Chinese and African immigrant groups. This suggests that voter restrictions, which others show depress turnout among voters of color, are being mobilized by tapping into public animosity specifically toward Mexican immigrants.

Figure 1 – Impact of feelings towards immigrants on perceptions of voter fraud

General immigrant resentment, ethnocentrism, and electoral integrity

We also measure resentment of immigrants (which others have measured as believing that immigrants increase crime, diminish the use of English, dampen a citizen’s political influence, and that new immigrants do not deserve any more special treatment than European immigrants). Our results provide strong evidence that a general measure of immigrant resentment is a robust predictor of voter fraud perceptions.

We still find other relevant factors: support for Trump, distrust of government, black resentment, and partisanship are also influential. However, they all have relatively smaller effects than immigrant resentment. Consistent with other studies, we find that Democrats and Independents are less likely than Republicans to believe voter fraud occurs. We also find that immigrant resentment has a larger effect than a person’s animus toward African Americans, which could be a reflection of recent elite rhetoric framing the issue of voter fraud as a problem of immigrants breaking the law.

Anti-immigrant attitudes also extend to beliefs about election integrity. The 2012 American National Election Study includes questions in the postelection wave that ask how often in our country “votes are counted fairly” and “election officials are fair,” which are narratives closest to the election fraud allegations that frequently appear in election reform debates in the United States.

Using responses to six ANES questions on immigration, we create an anti-immigrant scale. We also create an Ethnocentrism Scale based on stereotype questions that ask the degree to which particular groups (Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians) are “hard working” and “intelligent.” We find that an increase in the anti-immigrant attitudes increases the odds of believing that neither votes were counted fairly nor election officials are fair. An increase in the ethnocentrism scale yields a somewhat weaker but statistically significant relationship with pessimism toward election integrity. In addition, we find a stronger impact of ethnocentrism and anti-immigration attitudes on voter fraud beliefs when the sample is restricted to non-Hispanic Whites.

“That’s right, no amnesty!” by Mike Schinkel is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Shopping for New Venues, Redefining Policy Images

We find that a person’s animosity toward immigrants—particularly, immigrant resentment—is a highly influential predisposition since its components reflect attitudes toward crime, deserving membership in the polity, perceived threats to American traditions, and fears about losing political influence. Recent political rhetoric frequently combines these elements by linking immigration with crime and voter fraud in particular. Our findings show that similar attitudes are called to mind when people attempt to enumerate instances of voter fraud in US elections.

Our findings highlight Trump’s strategic choice of Kris Kobach as the Vice Chair of the beleaguered election integrity commission. Kobach further emboldens two popular political agendas: restricting US immigration and participation in US elections. Kobach, a former Kansas Secretary of State now currently running for governor, once coauthored the controversial Arizona’s strict anti-illegal immigration law SB1070. He represented 10 Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents who attempted to challenge Obama’s deferred actions that gave millions of undocumented immigrants reprieve deportation, going on the record by saying that recipients should go home and get in line as well as favoring that the whole family of DACA recipients should be deported the whole family.

Such an appointment is indeed a signal that the Trump Administration is interested in tapping American ethnocentric values to solidify public support for measures to restrict participation of eligible voters in future US elections. Further, it is also a sign that policy entrepreneurs like Kobach are attempting to move the image of allegedly tainted US elections away from institutions of election administration to newer institutional venues responsible for national security and border enforcement. The public should understand elite strategies to redefine the policy image of tainted elections as an immigration problem more for its partisan motivation to win elections and less for its objective to actually restore integrity. As others have noted, elections are messy, but not necessarily filled with intentional fraud.

- This article is based on the paper, “Immigrant Resentment and Voter Fraud Beliefs in the U.S. Electorate” in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2kliPkB

_________________________________

About the authors

Adriano Udani – University of Missouri – St. Louis

Adriano Udani – University of Missouri – St. Louis

Adriano Udani (@adrianoudani) is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Missouri – St. Louis with a joint appointment in the Public Policy Administration Program.

David Kimball – University of Missouri – St. Louis

David Kimball – University of Missouri – St. Louis

David Kimball (@kimballdc) is Professor of Political Science at the University of Missouri – St. Louis.

President Gerald Ford stated in Rockford, IL, March 11, 1976:

“People say … why don’t you expand that program, why don’t you spend more Federal money?…

I don’t think they have understood one of the fundamentals …

I look them in the eye and I say,

‘Do you realize that a government big enough to give us everything we want is a government big enough to take from us everything we have?'”