Compared to past decades, a far higher percentage of Americans now attend college. But those who graduate often must contend with high levels of student debt, and face a more uncertain labor market which can lead to underemployment. In new research which looks at post-college underemployment, Kody Steffy finds that those graduates who considered that they were voluntarily underemployed tended to be middle-class, had more access to support, and felt more positively about the experience. By contrast, those who felt that their underemployment was not a choice were often from working-class backgrounds and struggled more.

Compared to past decades, a far higher percentage of Americans now attend college. But those who graduate often must contend with high levels of student debt, and face a more uncertain labor market which can lead to underemployment. In new research which looks at post-college underemployment, Kody Steffy finds that those graduates who considered that they were voluntarily underemployed tended to be middle-class, had more access to support, and felt more positively about the experience. By contrast, those who felt that their underemployment was not a choice were often from working-class backgrounds and struggled more.

When I first decided to undertake a study of underemployed college graduates, I expected many things. I expected a familiar story of a fading American Dream. I expected narratives of perseverance in spite of struggle. And above all, I expected to write a classic sociological study of workers struggling to get by in a system that works against them. Indeed, I did find these things—particularly among graduates from working-class backgrounds. But I also found something I wasn’t expecting: a type of “voluntary underemployment” arising not from labor market struggle but from deliberate, often value-driven life choices.

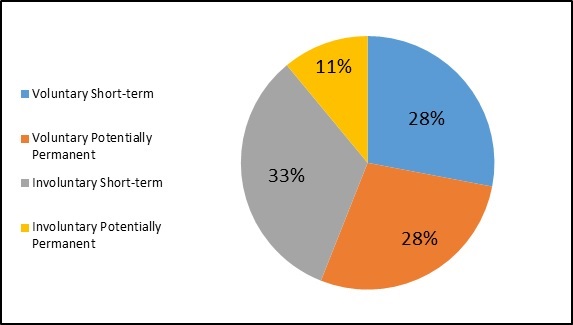

In my interview-based study of college graduates working in jobs that do not require degrees, over half of the respondents described their journey into underemployment as intentional. For some, this voluntary underemployment was expected to be short-term. Others anticipated it to be potentially permanent.

Figure 1 – Underemployment experiences amongst college graduates

Source: Steffy (2017), Willful Versus Woeful Underemployment.

Those who thought of underemployment as voluntary and hopefully short-term are the type of young adult often depicted in media stories about millennials. In general, these respondents were underemployed because they were concerned with discovering their unique passions in life. One respondent described her motivating logic this way: “I think right now I really am focused on what I need in life to be happy and working on [finding] a career that I really, really love and that totally shapes me as a person.” In the meantime, she was content with her position in retail.

More interestingly, some respondents who thought of underemployment as voluntary also saw it as potentially permanent. In other words, their aspirations did not include the type of work typically expected of college graduates. These respondents were trying to forge a life consistent with their value commitments—ranging from traditional religious beliefs to sustainable living and leftist politics. They had no concrete plans of ever establishing traditional careers. One respondent, who graduated at the top of her class, put it this way: “I have a lot of critiques of the capitalist system and how it affects people on an emotional level. And I think that I’m trying to withdraw from feeling those pressures and trying to live an emotionally fulfilling life.”

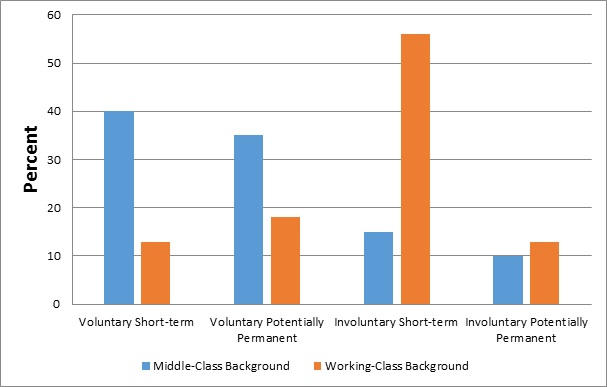

Yet this story also has a dark underbelly. Put bluntly, voluntary underemployment was experienced primarily by graduates who had been raised in middle-class families and had access to middle-class resources. Overwhelmingly, respondents from working-class backgrounds experienced underemployment as a struggle. These graduates usually detailed persistent efforts to find more adequate employment. Some reported having applied to hundreds of jobs. One had been scammed after responding to job ads posted to online classifieds. Another respondent had been pressured by her family to visit a temp agency and narrowly avoided having to work in the factories her parents had labored in throughout her childhood. A few respondents experiencing involuntary underemployment had accepted their fates as low-wage workers. Yet the majority remained focused on reaping the rewards they believe a college degree should bring: financial stability and career fulfillment.

Figure 2 – Underemployment Experiences, by Social Class Background

Source: Steffy (2017), Willful Versus Woeful Underemployment.

Predictably, the consequences of underemployment are different for those who see it as voluntary and those who see it as involuntary. In particular, the experience was far less stressful for those underemployed by choice than for those involuntarily underemployed. The key difference here is feeling in control of one’s life versus feeling like a failure.

Among the involuntarily underemployed—mostly from working-class backgrounds—one respondent had to postpone our interview due to severe anxiety. Several others felt that their families were disappointed in them. One respondent, who had graduated with a triple major and perfect GPA, reported lying to acquaintances and saying she was still in school rather than discuss her job. She summed up her feelings: “I often think about how long I’ve worked at [big box store] and how much longer I’m going to, and what I’m doing about it. But that doesn’t always motivate me to do something about it. Because I’m kind of at a point where I’m just discouraged, like, ‘Why doesn’t anyone want to hire me?’ Or like, ‘Why can’t I get a job that I really want?’ Or, ‘Will I always work there even though I don’t want to?’”

This contrasts dramatically to the experiences of those respondents, mostly raised middle-class, who see underemployment as a chosen path. These respondents generally reported supportive family and friends, who understood the choices they had made. For example, one graduate who was pursuing a sustainable lifestyle rather than a career reported her parents sending her articles on tiny home living. A frequent utterance was, “They’re happy if I’m happy.” Combined with financial support (or the comfort of knowing financial support was available), this social support reassured these graduates that they were on the right path. As one respondent put it, “I’m really happy right now. I feel great. I’m excited about upcoming opportunities and I enjoy my days right now a lot.”

Photo by Faustin Tuyambaze on Unsplash

The experiences of those who see underemployment as voluntary vs. involuntary are not just different. They are unequal. For most middle-class graduates, underemployment is anticipated and liberating. For most working-class graduates, it is a time of unexpected struggle.

Post-college underemployment is a deeply classed experience

In the end, my interviews underscore the roles of both cultural and economic factors in contributing to graduate underemployment. Culturally, the story is uplifting. Many graduates are doing all they can to forge lives consistent with their values. These respondents generally come from places of privilege, but they are nevertheless taking a risk by foregoing pursuit of the American dream in search of a meaningful life.

Economically, however, the interviews highlight the deeply classed nature of the American experience. Overwhelmingly, the first-generation graduates in the sample have found themselves victims of socioeconomic processes beyond their control. Despite having done all they were told to do—making it into and graduating from a highly regarded university—they find themselves struggling. The American dream, for them, remains elusive, just as it had been for their parents.

There are implications here. At the university level, more needs to be done not only to attract, admit, and retain first-generation students, but also to support them as they try to capitalize on their degrees. Many lack the social, financial, and cultural capital to successfully navigate the turbulent waters of the labor market. Given the rising costs of higher education in the United States, universities would do well to offer them better support. At the policy level, lawmakers need to recognize that students’ financial investments in higher education are not always rewarded—even among students who do all they are supposed to. At a time when programs like public sector loan forgiveness are under threat, this acknowledgement is needed more than ever. As is, the lesson many first-generation college students learn is that their hard work and financial investments have left them doubly disadvantaged—deeply in debt with uncertain earning potential. On a moral level, this is unacceptable.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Willful Versus Woeful Underemployment: Perceived Volition and Social Class Background Among Overqualified College Graduates’, in Work and Occupations.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2AaBHJm

_________________________________

About the author

Kody Steffy – Michigan State University

Kody Steffy – Michigan State University

Kody Steffy is Assistant Professor at Michigan State University. A cultural sociologist, he focuses primarily on work, religion/morality, and their intersection during periods of social change and transformation. His current projects examine how young adults experience and respond to changing opportunity structures and the economic orientations of religious groups.