Using data on generic ballot results back to 1954, Dan Cassino argues that generic ballot measures are most useful in identifying the quality of candidates recruited by a party, not necessarily the outcome of the race. With Republicans expected to slightly underperform their standing on the generic ballot measure this year, the 2018 midterms could look like a wave election for the Democrats.

Using data on generic ballot results back to 1954, Dan Cassino argues that generic ballot measures are most useful in identifying the quality of candidates recruited by a party, not necessarily the outcome of the race. With Republicans expected to slightly underperform their standing on the generic ballot measure this year, the 2018 midterms could look like a wave election for the Democrats.

With a series of survey results showing that Democrats have an enormous lead over Republicans in the 2018 election for control of the House of Representatives, it’s worth asking what these generic ballot items really mean, and how well they predict what’s actually going to happen in November.

First, the basics. Generic ballot measures are a tool used by pollsters to ask voters which party they would vote for in an upcoming congressional election. These questions do not mention specific candidate names and can be used further in advance of the election than named candidate surveys, as the names of all of the candidates generally aren’t known until a few months before the election. There’s a long history of the sort of questions being used, with data going back to the 1954 midterm election.

However, the results of these questions often fail to measure the actual outcome of the race. In 2014 my colleagues and I ran two survey experiments in which we randomly assigned respondents to answer a generic ballot measure or a named candidate measure in Delaware and New Jersey. In Delaware, the named candidate, a well-known Lt. Governor running for the state’s lone seat in the House, outperformed the generic ballot by 10 points. In the 2010 New Jersey house races, where a Tea Party wave brought out a large number of strong Republican challengers, the named candidates outperformed their generic ballot support by 9 points.

The implication here is clear: the generic ballot question does a good job of measuring support for a generic candidate. If a specific, named candidate is better known and/or liked than “generic Republican” or “generic Democrat,” they’ll outperform the expectations set by the generic ballot measure; if they’re less known or liked, they’ll underperform those expectations. If a party systematically recruits better candidates than usual, or the opposition party systematically recruits worse than usual candidates, the generic ballot measure will be off. What makes a party able to recruit a large number of qualified candidates? Our previous analysis makes the case that the dominant factor is presidential approval: popular presidents attract better-than-generic members of their party to run; unpopular presidents scare them off. Indeed, the best predictor of error in the generic ballot item is Presidential approval 12 to 15 months before the election, corresponding to the time when candidates have to decide whether or not to run.

Wave Elections

The other moving part here is the vulnerability of the other party’s incumbents. When a party wins a lot of seats in a wave election (when one party makes major gains in the House and the Senate), they wind up with a lot of new incumbents that would probably have a hard time winning in a normal political climate. So, as political scientists have been pointing out for decades, the bigger the surge for a party, the bigger their likely decline in the next set of races.

So what does all of this mean for 2018? Republicans hoping that the generic ballot measures will simply be off are likely to be disappointed: the mean error of the generic ballot item in predicting actual election results for House elections is only 2.6 points, and there’s little sign of systematic error in the measures this cycle. Republicans hardly rode into office on a wave in 2016, meaning that they’re not defending too many weak first term incumbents, but there’s also a terribly unpopular Republican President in office. That means that Democrats would be expected to recruit better-than-generic candidates, but not have the benefit of a lot of easy seats to pick off. All told, our recruitment-based model expects that Republicans will slightly underperform their standing on the generic ballot measure, with an outcome about 0.3 points lower than the question would predict. Given how bad the generic ballot measure is for the Republicans right now – some polls show Democrats with an 18 point lead, though the mean lead right now is about 12 – this is bad news. Moreover, it’s not likely to get better: the story here is largely one of candidate recruitment, and those decisions have mostly already been made. In sum, Democrats should get their surf boards out: there looks to be a big wave coming.

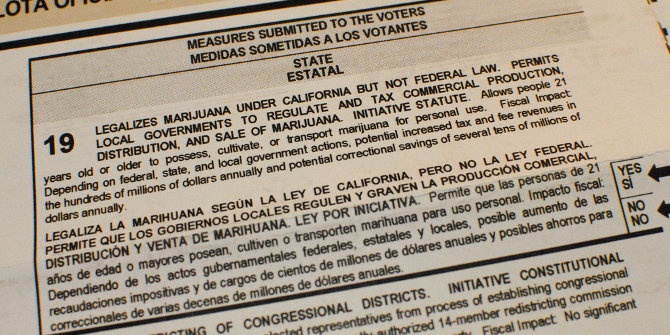

- “California Ballot Prop 19” by Brian Cantoni is licensed under CC-BY-2.0.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2DLJuAv

_________________________________

Dan Cassino – Fairleigh Dickinson University

Dan Cassino – Fairleigh Dickinson University

Dan Cassino is an associate professor of Political Science at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, New Jersey, who studies political psychology and polling. His most recent books are “Fox News and American Politics,” and “Social Research Methods by Example: Applications in the Modern World,” with Yasemin Besen-Cassino.

In California it was said that the more a political party identified itself with a controversial ballot initiative, the more it got hurt, even though the initiative was successful.

A really special one was the famous Proposition 8, in 2008. Of the four major ethnicities, the more an ethnicity supported Obama, the more it supported Prop 8.

I won a $20 bet with a politically much more savvy friend that Trump would beat Clinton in 2016. I now predict that the Republicans will get their clock cleaned in both 2018 and 2020. A non-Republican will be elected President in 2020. (Note the somewhat unusual wording there.)

That means that Democrats would be expected to recruit better-than-generic candidates.