During the 2016 election campaign and the early stages of his presidency, Donald Trump made repeated attacks on the integrity of federal judges. If his belligerence were to turn to the US Supreme Court, would the trust that Americans feel in that institution protect its reputation? In new research which examines how people’s views of the Court are affected by partisan attacks and praise, Miles T. Armaly finds that, in the face of such attacks, the reputation of the Court could be undermined among those who already support Donald Trump. People’s feelings about a particular politician who makes negative statements – not about the Court itself – he writes, are the main determinant of how effective these statements are.

During the 2016 election campaign and the early stages of his presidency, Donald Trump made repeated attacks on the integrity of federal judges. If his belligerence were to turn to the US Supreme Court, would the trust that Americans feel in that institution protect its reputation? In new research which examines how people’s views of the Court are affected by partisan attacks and praise, Miles T. Armaly finds that, in the face of such attacks, the reputation of the Court could be undermined among those who already support Donald Trump. People’s feelings about a particular politician who makes negative statements – not about the Court itself – he writes, are the main determinant of how effective these statements are.

The American public overwhelmingly supports the US Supreme Court, believes the institution is legitimate, and thinks it should be free to make independent decisions without the president or Congress getting in the way. Studies show that people believe this even when they dislike the decisions the Court makes, mostly because people appreciate its legal foundations. But, feelings toward many politicians are very strong; people tend to love President Trump or hate him, love Hillary Clinton or hate her. Rarely are people “lukewarm” toward visible politicians. So, what happens when a politician — about whom attitudes are fairly concrete – criticizes the Supreme Court? Do people alter their views to align with their preferred politician, or maintain their staunch loyalty to the Court?

These questions are important because the Supreme Court has no power to enforce its own decisions and relies on the elected branches to do so. The elected branches are unlikely to do anything that might cost them votes in the next election, so public acceptance of Court decisions is crucial. If a president or a noteworthy politician is capable of influencing support for the Court, there are very serious implications for the separation of powers. Namely, a politician could rhetorically alter public support for Supreme Court decisions, thereby reducing public willingness to demand that elected officials uphold Court rulings.

I was curious to determine if negative statements about the Supreme Court by a politician not associated with the judiciary could influence whether people alter their level of institutional support for the Court. To find out, I conducted two experiments – one about Hillary Clinton and one about Donald Trump.

Participants in the experiments were first asked a series of questions that measure how legitimate they believe the Supreme Court is; high scores indicate they believe the judiciary should be independent and free to make decisions without meddling by the other branches. For instance, questions ask respondents to say whether they agree or disagree, on a 5-point scale, with statements like “The Court gets too mixed up in politics” and “The Supreme Court ought to be made less independent so it listens a lot more to what the people want.” They were also asked if they thought the Court was liberal, conservative, or moderate. Some participants were randomly assigned to answer the legitimacy questions a second time. Others read the following sentence:

Recently, in a speech given to supporters, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton [in the Trump experiment: “president-elect Donald Trump”] made some controversial remarks regarding the United States Supreme Court. Below, some of her [his] critiques will be paraphrased. Please indicate your level of agreement with Hillary Clinton’s [Donald Trump’s] statements.

Then, these respondents were presented with the original questions measuring legitimacy, but were led to believe that Clinton (in the first experiment) and Trump (in the second) had made those negative statements about the Court. For instance, they read “Hillary Clinton commented that “The Supreme Court ought to be made less independent” so that it listens a lot more to what the people want. Do you agree or disagree?” In order to determine if people changed their minds regarding the legitimacy of the Supreme Court after hearing “nasty” statements by a politician, I simply subtract the average response from the first time they answered the questions from the average response from the second time they answered the questions. Finally, I measure people’s feelings toward each politician on a 0-100 scale, where 0 means a person is “cold” or dislikes the politician and 100 means they are “warm” or like the politician.

“Supreme Court of the United States” by Phil Roeder is licensed under CC BY 2.0

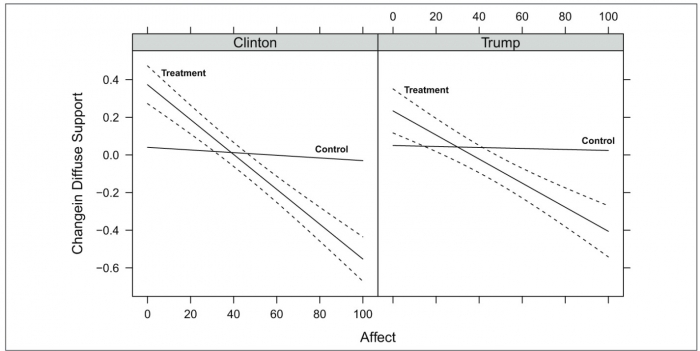

The general expectation is that people who like Hillary Clinton will, upon hearing her negative comments about the judiciary, decrease their level of institutional support for the Court. Conversely, people who dislike Clinton will increase their support for the Court. The same is true for those who were led to believe Donald Trump made such statements. As Figure 1 below shows, this is precisely what the data reveal. People who were not exposed to statements by a politician are resolute in their evaluations of the judiciary; they didn’t change their minds about the Court’s legitimacy. However, as the left panel demonstrates, people who dislike Hillary Clinton increase their assessment of the Court’s legitimacy; people who like Hillary Clinton decrease their support upon hearing that she does not like the Court. The same is true of the Donald Trump sample; his negative comments about the Court lead to an increase in support among those who dislike him and a decrease among his supporters.

Figure 1 – Effect of treatment on change in diffuse support across affect toward Clinton (left) and Trump (right)

There are two reasons a person might be influenced by a politician’s statements about the Court. On the one hand, members of the public look to politicians that they like to inform their attitudes about politics. In his 2012 book of the same name, Gabriel Lenz shows that citizens “follow the leader,” meaning they adopt a politician’s policy views after choosing the candidate, as opposed to choosing the candidate based on policy views. Similarly, studies show that feelings, or affective attachments, to political figures are extremely powerful. So, people may simply embrace their preferred politician’s attitudes about the Court; they may think “I like Trump. If he hates the Court, I must too.”

On the other hand, studies show that people have a difficult time determining if the Supreme Court is liberal, conservative, or moderate. But, people generally tend to know whether a particular politician is liberal or conservative. So, a person might be able to gauge whether the Court tends to favor his or her preferred policy based on whether he or she think a notable politician disagrees with the Court on policy. For example, if Hillary Clinton – who is liberal – said she disagrees with the Court, one might reasonably presume the Court is conservative, and vice versa for Donald Trump. Thus, people might obtain legitimate ideological information about the Court and determine that they are or are not close to it in terms of policy preferences.

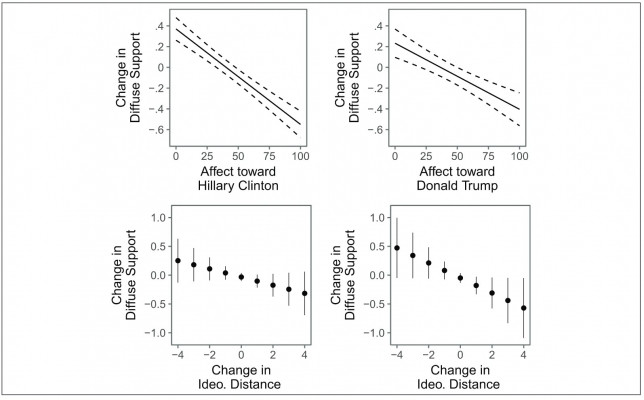

To determine which of these two options influences evaluations of the Court’s legitimacy, I compared respondents’ feelings toward each candidate with whether or not they updated how distant they perceive themselves to be from the Court in ideological terms. That is, I subtracted how far a person felt from the Court on a 5-point scale as measured before the experimental treatment from how far they felt on the same scale after the experimental treatment. The expectation is that if people learned from the politician that they were further away from the Court in terms of policy preferences than they initially thought, they would decrease their support for the judiciary. If they learn that the Court rules in their preferred way more often than they thought – that is, if they learn they are closer to the Court than expected — they should increase their support.

As Figure 2 below shows, people are largely influenced by their affect toward the politician, and only moderately influenced by new information about whether the Court represents their policy views. More specifically, people who learn that they are further from the Court than initially believed decrease their support for it, but this is only true for the Trump sample. In no instance do people who realize they are closer to the Court increase their support. In both samples, there is a strong negative relationship between people’s feelings and the change in legitimacy, just as described above. This suggests that there is a greater effect of personal feelings toward a politician than learning information about whether the judiciary represents one’s policy interests. In other words, attitudes toward the Court are guided by feelings, not ideological similarity.

Figure 2 – Effect of affect and change in ideological distance on diffuse support

My results suggest that extra-judicial actors like presidents can harm the Supreme Court’s legitimacy, which usually tends to be quite stable and difficult to diminish. While studies about institutional legitimacy usually yield comforting results, the results do not. They suggest that the elected branches can induce or exacerbate the Court’s “crisis of legitimacy” and potentially undermine public support for the Court.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Extra-judicial Actor Induced Change in Supreme Court Legitimacy’, in Political Research Quarterly

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2szEzxd

_________________________________

About the author

Miles T. Armaly – University of Mississippi

Miles T. Armaly – University of Mississippi

Miles T. Armaly is an assistant professor at the University of Mississippi, where he studies judicial politics, public opinion, & political behavior.

Interesting well-done study.