In spite of an ever-growing list of scandals and criminal indictments, President Trump’s job approval rating has rallied from its December nadir. Trump’s approval rating is now in the low 40s – where Reagan’s and Clinton’s approval stood around the time of their first midterm elections. Given Trump’s controversial statements and the various crises which have gripped the White House since the inauguration, why is the 45th president’s approval rating so high? Matthew D. Atkinson, Darin DeWitt, and Joseph E. Uscinski find that, as has been the case with past US presidents, Trump’s approval rate ebbs and flows with the public’s perception of the economy. A relatively buoyant economy, they write, is keeping Trump’s approval rating higher than it might otherwise be. This says something particularly damning not just about approval ratings, but about voters, elections, and democracy as well.

In spite of an ever-growing list of scandals and criminal indictments, President Trump’s job approval rating has rallied from its December nadir. Trump’s approval rating is now in the low 40s – where Reagan’s and Clinton’s approval stood around the time of their first midterm elections. Given Trump’s controversial statements and the various crises which have gripped the White House since the inauguration, why is the 45th president’s approval rating so high? Matthew D. Atkinson, Darin DeWitt, and Joseph E. Uscinski find that, as has been the case with past US presidents, Trump’s approval rate ebbs and flows with the public’s perception of the economy. A relatively buoyant economy, they write, is keeping Trump’s approval rating higher than it might otherwise be. This says something particularly damning not just about approval ratings, but about voters, elections, and democracy as well.

Scholars of the American presidency recently ranked President Trump as the worst president of all time. This means that Trump’s presidency – after only one year – was considered worse than the failed presidencies of Richard Nixon, Warren Harding, Andrew Johnson, and James Buchanan. Despite the experts, Trump currently enjoys a 42 percent approval rating. This level of approval is comparable to similar ratings faced by the 9th greatest president, Ronald Reagan, and the 13th greatest president, Bill Clinton, prior to their first midterm elections. Furthermore, Trump’s approval numbers are far better than George W. Bush’s nadir of 25 percent. While Trump’s approval rating could be higher, many political observers – including BloombergView’s Jonathan Bernstein – wonder why it is as high as it is and whether new political dynamics shape aggregate approval. Should we be surprised that the president who experts rate as the worst ever sustains a 42 percent approval rating? As it turns out, no.

Historically, a leader’s political approval has turned on bread and butter issues, with voter evaluations framed in terms of “What have you done for me lately?” All around the world, the answer to this question drives fluctuation in political support and election outcomes.

In light of the tragic breakdown of American political institutions and culture, popular and scholarly accounts of American politics discount the role of economic fundamentals in shaping election outcomes as well as presidential approval. For instance, in advance of the 2016 presidential election, pundits and political scientists – ourselves included – suggested that Donald Trump was undermining the economic fundamentals model that historically accounted for election outcomes. Yet, in 2016, the fate of American politics turned on short-term economic performance and the popular vote outcome was precisely in line with economics-based predictions.

The lesson of 2016 is clear: the voters that swing elections are still obsessed with economic performance. Yet, as pundits and scholars begin to wipe the egg from our collective face, we fear that the lesson of the 2016 presidential election has been forgotten – if indeed it was ever heeded in the first place. In discussing the 2018 and 2020 elections, most political observers emphasize identity politics, disputes over “the truth,” and the perpetually propagating scandals and allegations surrounding the Trump administration. These ideas are important, but the salacious headlines they generate may lead them to be overemphasized when accounting for the dynamics of public opinion. Neglecting the role that economic fundamentals plays in explaining public opinion is a devastating mistake because it impedes our ability to effectively address the American political system’s vulnerability to authoritarianism – namely, the fact that, voters do not seem to hold leaders accountable for misdeeds because “election outcomes are, in an important sense, random.” In other words, Trump’s chance at a second term will hinge on short-term economic fluctuations rather than on his personal qualities, long term performance, or adherence to constitutional principles.

Photo credit: Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead

A long legacy of political science research shows that economic fundamentals drive aggregate public opinion. In a provocative illustration of this idea, public opinion scholar John Zaller ponders: What if Richard Nixon presided over Bill Clinton’s strong economy and Clinton, in turn, presided over Nixon’s weak economy? Under these conditions, Zaller suggests that perhaps Nixon would have served out his term and Clinton would have left office. But what of today?

Does the fate of presidents and their parties in Congress still turn on economic performance? Or is everything different in what Paul Krugman calls “Trumpistan”? To address these questions, we consider the dynamics of presidential approval during the Trump presidency.

In The Macro Polity, political scientists Robert Erikson, Michael MacKuen, and James Stimson show that, before Trump, the fate of presidents turned on national economic conditions. Likewise, as we will see, Donald Trump’s approval rating has followed the ebbs and flows of citizens’ perceptions of the current economic conditions. According to Erikson, MacKuen, and Stimson, all presidents have a unique baseline of approval. Trump’s baseline is low. This is no surprise for a president who lost the popular vote, has made little effort to appease voters outside his base, and who has decided to forego the traditional presidential honeymoon by announcing his divorce from the news media before he even took office. But the fluctuations in his approval rating are completely consistent with the conventional economic model presented in The Macro Polity. In sustaining a 42 percent approval rating, the worst president of all time is not defying gravity. Rather, he is the beneficiary of a strong economy.

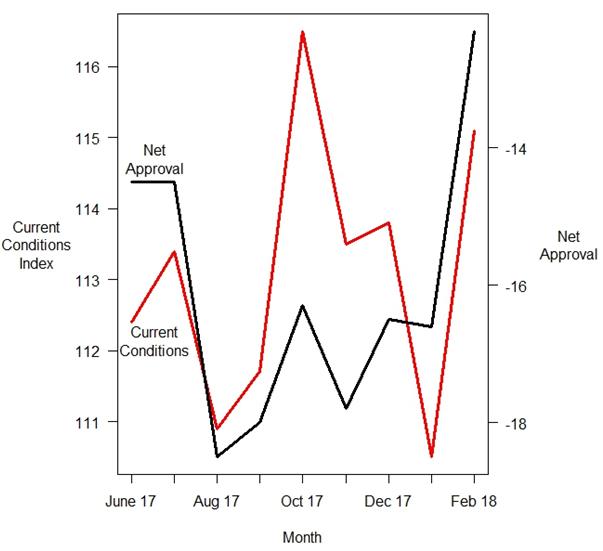

To demonstrate our claim, we use the best available operationalization of the “What have you have for me lately” question that motivates swing voters, the monthly Current Conditions Index from the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers. In Figure 1 below, we plot the University of Michigan’s Current Conditions Index. We also plot President Trump’s Net Approval, which is calculated by subtracting President Trump’s disapproval rating from his approval rating. We measure Net Approval on the first of each month, as reported by the Real Clear Politics poll average, as this coincides with the fielding of the corresponding Survey of Consumers. Our plot begins in June 2017, when the public typically begins to hold a new president accountable for the state of the economy.

Figure 1 – Economic conditions and presidential approval

In Figure 1, the big moves in Trump’s approval rating coincide with analogous moves in the economy. While the association between Net Approval and the Current Conditions Index is not perfect, the observed correlation under President Trump is identical to the historical correlation reported in The Macro Polity, the book that authoritatively established the strong causal relationship between economic performance and presidential approval. The plot implies that the conventional economic model of presidential approval continues to apply in the Trump era.

Presidential approval is the mother’s milk of national political power: it determines the capacity of the president to enact significant policy, drives tides in congressional midterm elections, and shapes political will on Capitol Hill for investigating and impeaching the president. To date, Trump’s power and his level of support in Congress have blown with the economic winds and we would be foolish to ignore the possibly that Trump’s presidency will rise and fall with an economy that in the short term is largely out of his control.

While Donald Trump has certainly inflamed polarization on the left and the right, our evidence suggests that the swing voters who shift approval ratings and decide elections haven’t changed all that much. Thus, intensified partisanship will not make or break Trump. If the bottom falls out of the economy, our evidence implies that his approval numbers will face the same fate as George W. Bush’s. Likewise, at critical points in time such as the coming midterm elections this November, a lucky roll of the random die that is short-term economic performance could well save Trump’s bacon.

The idea that presidential success is determined by economic performance has been tested by scandal before. For instance, in what John Zaller calls “Monica Lewinsky’s Contribution to Political Science,” Bill Clinton’s affairs and impeachment taught us that “the public is, within broad limits, functionally indifferent to presidential character.” Twenty years on, Trump’s contribution is to test the astonishing breadth of those limits and, thus far, uphold the robustness of the Lewinsky lesson.

We ignore that lesson at our peril. As we engage in a national conversation about Russian bots and the effects of social media, the biggest cause of political dysfunction continues to hide in plain sight: the myopic assessments on which the public has always based its opinions and the fallout ensuing from the breakdown in the party system that used to insulate us from the implications of that myopia.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2H5dm8h

_________________________________

About the authors

Matthew D. Atkinson – Long Beach City College

Matthew D. Atkinson – Long Beach City College

Matthew D. Atkinson is an assistant professor of political science at Long Beach City College.

Darin DeWitt - California State University Long Beach

Darin DeWitt - California State University Long Beach

Darin DeWitt is an assistant professor of political science at California State University Long Beach.

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

Joseph E. Uscinski is an associate professor of political science at University of Miami and co-author of American Conspiracy Theories.