Like many American cities, Washington DC is experiencing a squeeze in its affordable housing: population increases and declining stocks of government subsidized housing are making it harder for low-income households to find somewhere to live. In new research, Kathryn Howell looks at how existing assisted housing in Washington, DC is being preserved in the face of gentrification and funding challenges. She writes that preservation is a long and complex process that engages diverse stakeholders from tenants and tenant organizers to local and federal agency staff.

Like many American cities, Washington DC is experiencing a squeeze in its affordable housing: population increases and declining stocks of government subsidized housing are making it harder for low-income households to find somewhere to live. In new research, Kathryn Howell looks at how existing assisted housing in Washington, DC is being preserved in the face of gentrification and funding challenges. She writes that preservation is a long and complex process that engages diverse stakeholders from tenants and tenant organizers to local and federal agency staff.

Since the late 1990s, Washington, DC has experienced rapid growth. The city’s population has grown by almost 25 percent since 2000, led largely by a 48 percent rise in the white population. Inflation-adjusted median income has also grown, by almost 30 percent in the same period. This growth has put pressure on affordable housing in the Capital. While the number of low-income households has remained stable, the number of units that they are able to afford has fallen by more than 50 percent. The city also lost roughly 12 percent of its government subsidized stock during that period. These trends reflect the national picture also illustrated in cities such as Seattle, New York and Chicago.

For those concerned about housing affordability, the focus has been on how to build new affordable units using planning tools like zoning and mandatory inclusionary housing or federal subsidies like the Low Income Housing Tax Credit. However, cities are increasingly looking to the preservation of the existing affordable stock as a key mechanism for retaining a diverse resident base in the midst of growth and gentrification and preventing the loss of deeply affordable subsidized housing. At the same time, local and state governments face the uncertainty of the future of federal housing support in budget appropriations, pushing them to develop different ways of addressing ongoing problems. But developing new funding sources and programs for the complex process of preservation requires multiple private and government stakeholders, shared governance and access to data.

One example of the process for preservation and loss is Museum Square Apartments in Washington, DC. In 2015, the owner of Museum Square One Apartments notified his tenants that they would opt-out of its nearly 40 year-old Section 8 contract the following year. The 301-unit building, located in the midst of a massive luxury apartment boom, housed a large portion of the Chinatown neighbourhood’s remaining Asian seniors. It was built as part of Washington, DC’s Urban Renewal Program active from 1949 to 1974. The City acquired the property on which the building now stands and sold it at a discount to a developer who used funding from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to construct Museum Square One.

The owner’s 2015 decision to opt out of the subsidy was just one piece of the building’s troubled history. Starting in 2002, as DC’s former Mayor announced his goal to attract 100,000 net new residents by 2012, Museum Square One faced constant threats to its conditions, subsidies, and tenants’ rights that would culminate in the 2015 opt out. Tenant organizers and government agencies reported fires in the building and deteriorating conditions; the owner’s vowed not to improve conditions, in spite of applications for new funding. At the same time, because of Washington’s unique Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, which gives tenants the right of first refusal when a building is sold or razed, there may still be a chance to preserve the building and retain some of the historic community that build the neighbourhood.

The process for opting out of a federal subsidy is clear: a building owner notifies the Department of Housing and Urban Development of his or her intention to opt out, a notification is sent to the city, the city’s Housing authority issues enhanced vouchers to the tenants who then decide to move or stay. However, the Museum Square One case is just one example of the way affordable housing leaves the subsidized stock, as well as the efforts made by a broad group of stakeholders to try to preserve it.

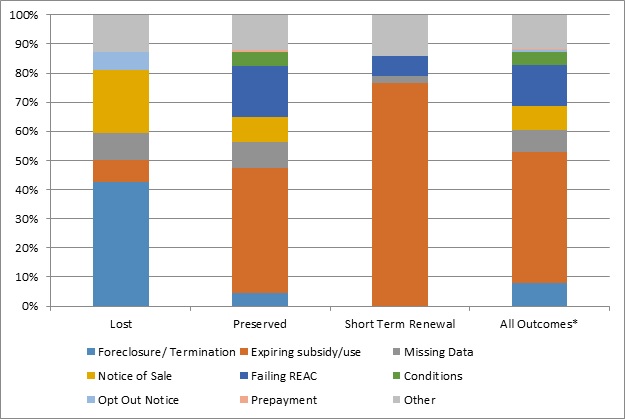

Because of the diverse scale impacts of affordable housing – city, neighbourhood, building and tenant – as well as the dimensions of funding, code enforcement and daily living, there must be an avenue through which data can be shared to create a more complete picture of the building’s status. In the DC case, these data are shared through the DC Preservation Network’s preservation catalogue and monthly meetings. The DC Preservation Network is a monthly meeting of preservation stakeholders from tenant organizers to federal government staff. Figure 1 shows a snapshot of network data demonstrating the outcome of more than 30,000 buildings based on the reason they were at risk of loss from the subsidized stock. Although almost half the buildings were on the agenda due to an expiring subsidy, expiring subsidies only represented three of those which were lost. In fact, an expiring use alone was rarely a concern among participants. The bulk of DC’s lost buildings came as a result of a termination of the contract after a failed inspection. However, many of the buildings that were lost came with more than one challenge.

Figure 1 – Reasons for Appearance on the DCPN Agenda by Outcome, 2008-2015

*This column includes buildings that are categorized as “ongoing” in the data

Source: DC Preservation Network

The variety of challenges facing buildings suggests that preservation is a long and complex process that engages diverse stakeholders from tenants and tenant organizers engaged in the daily experiences of the building to local and federal agency staff. Opt-outs and terminations of subsidies were ultimately rare in Washington because stakeholders had access to significant local preservation resources. These stakeholders used a mix local policies, including local tenant protections, flexible funding sources such as DC’s Housing Production Trust Fund, and laws that enabled access to the housing market such as the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, which gives tenants the right of first refusal when their building is for sale. This case offers powerful support for increased collaboration between stakeholders and meaningful local laws and flexible funding for the preservation of affordable housing.

Unlike the on-paper straightforward process for a building owner to opt out of a federal subsidy I describe above, preservation and loss often take years with multiple opportunities for intervention. Residents often register conditions complaints, face illegal evictions or see repeated short term renewals (fewer than five years) of the building’s subsidy before the building is ultimately preserved or lost. In Washington, buildings were tracked by the preservation network for an average of 16 months before they were lost – many of those buildings had been tracked multiple times by the group, suggesting that there are clear opportunities for stakeholders to engage with the building owner, residents and funders.

While Washington, DC offers a critical illustration of the paths assisted buildings take as they are lost or preserved, it also demonstrates the necessity of developing local tools to intervene. Federal resources have declined for 40 years in the United States, leaving many cities and states, regardless of the market, at a loss to support the development and preservation of affordable housing. However, even with federal resources, local contexts vary, suggesting that laws and programmes should be developed locally to address the variation in governance, market, housing stock, and resident needs. Many cities – like the District of Columbia – have begun to understand that production of units using federal funds only approaches a portion of the problem in the face of the growth in many US cities that has made neighbourhoods unaffordable for low- and moderate-income households.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Neighbourhoods, local networks, and the non-linear path of the expiration and preservation of federal rental subsidies’ in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2HYyY7X

About the author

Kathryn L Howell – Virginia Commonwealth University

Kathryn L Howell – Virginia Commonwealth University

Kathryn Howell is an assistant professor of urban and regional planning in the Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her work focuses on affordable housing and public spaces to explore neighborhood change and governance. She has specifically looked at the preservation of affordable housing in Washington, DC, examining the intersection between policies, governance and the built environment. She was previously a practitioner in local government developing housing and community development policy in Washington, DC and Maryland agencies. She holds a PhD in Community and Regional Planning from the University of Texas at Austin, a Master of Public Policy from the Johns Hopkins University and a Bachelors in Political Science from the University of Georgia.