California US House Representative, Republican Duncan Hunter has been in the news this week, following extensive allegations of misuse of campaign funds. Anna Mitchell Mahoney writes that cases like Hunter’s illustrate that a great deal of political relationship-building is based on gatherings where women are often unwelcome. She argues that by creating a specific space for women, women’s caucuses – as are often found in state legislatures – can accelerate legislative collaboration and advocate for women’s advancement.

California US House Representative, Republican Duncan Hunter has been in the news this week, following extensive allegations of misuse of campaign funds. Anna Mitchell Mahoney writes that cases like Hunter’s illustrate that a great deal of political relationship-building is based on gatherings where women are often unwelcome. She argues that by creating a specific space for women, women’s caucuses – as are often found in state legislatures – can accelerate legislative collaboration and advocate for women’s advancement.

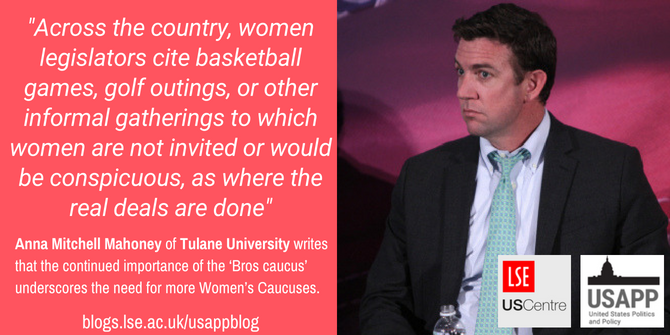

In a recent Politico story which details inappropriate behavior by Representative Duncan Hunter (R-CA) now under investigation for misuse of campaign funds, aides characterized his social network in Congress as the “bros caucus”. In legislatures, caucuses are alternative organizing mechanisms to committees and parties for legislators with shared interests or identities. Caucuses allow legislators to express certain identities, thereby highlighting their expertise in certain legislative areas and demonstrating their commitment to certain constituencies. Caucus members are able to build relationships and gain information useful for accomplishing their personal and legislative goals. Identity caucuses, those that represent larger constituency groups based on race, gender, or other categories, have an important symbolic power signaling governmental legitimacy to their constituents and amplifying the voice of marginalized citizens.

Representative Duncan Hunter’s financial scandal led to the exposure of other questionable behavior, but he is certainly not alone in participating in a bros’ caucus. In state legislatures all over the country, women are navigating these gendered work environments sometimes on their own and sometimes as a collective. While my research investigates how women’s caucuses form and what they accomplish, Rep. Hunter’s story illustrates why women legislators continue to need them.

My research on women’s state legislative caucuses shows that these organizations do not necessarily have policy as a focus and may exist for the purpose of socializing and building relationships among women legislators. Many women’s caucuses were created specifically to reject masculine dominance of legislatures or bro’s caucuses (formerly known as “the old boy’s network”). For example, the Women Legislators of Maryland organized in 1972 following abhorrent behavior by legislative leadership that consistently excluded women from political power. In 2009, the New Jersey Women’s Legislative Caucus was created with their first action item being the passage of the Party Democracy Act, which made transparent party electoral rules that they felt had been used to discriminate against women candidates on both sides of the aisle.

In defending his buying food and alcohol with his campaign credit card, Rep. Hunter is quoted as saying, “Any time you walk in [to the Capitol Hill Club], its work,” he said. “That’s why we go there.” Taking him at his word, Rep. Hunter is acknowledging what women legislators have known forever – that much of the business of legislating occurs in social situations – where women are not welcome or comfortable. Across the country, women legislators cite basketball games, golf outings, or other informal gatherings to which women are not invited or would be conspicuous, as where the real deals are done. This phenomenon is not exclusive to politics, women in all types of business report similar conditions.

“Duncan Hunter” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Creating a caucus establishes a specifically women’s space within a male-dominated legislature. In 2016, there were 22 women’s caucuses in states across the US as well as two at the federal level: the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues in the House and the Women’s Supper Club in the Senate. While some of these organizations have the purpose of creating and passing legislation, many of these groups are only social, to establish bonds among and between women. Many women legislators in caucus states appreciate an alternative to other social events that often involved alcohol, the underlying concern being men’s inappropriate behavior connected with drinking at legislative events. With or without alcohol, between October 2017 and January 2018, 18 men state legislators accused of sexual harassment resigned or otherwise faced consequences due to sexual harassment claims in over 12 states. Another 25 lawmakers accused of sexual harassment ran for re-election: 15 advanced to general elections and seven went unchallenged in primaries.

Women create their own caucuses to fix this problem building spaces that are associated with positive outcomes for not only women legislators but also constituents and the institutions of which they are a part. My colleague Mirya Holman and I have found that under certain conditions women’s caucuses accelerate collaboration as the share of women in the institution increases. Collaboration between women also continues in the face of increased polarization in the presence of a caucus, indicating that women’s caucuses can play a role in mitigating the gridlock present in today’s politics. Certainly bipartisan efforts by women in the US Senate have been credited with averting disaster on a number of fronts including the government shutdown in 2013.

So how do we get more women’s caucuses and fewer bros’ caucuses? Successful attempts at caucusing occur when savvy entrepreneurs properly read their political context and convince potential participants that collective action is the solution to their shared challenges. These entrepreneurs neutralize opposition, sometimes by compromising on their own goals for the sake of the group. For example, in partisan environments, establishing a social caucus enables women to support each other without demanding consensus on political issues where there is no common ground. Deferring to seniority and other informal norms, entrepreneurs can avoid petty power plays and establish groups that train women to run for office, distribute scholarships to young women, and advocate for women’s advancement to leadership within the legislature, all the while establishing relationships that can facilitate shared policy goals when the political context is right.

Eliminating bros’ caucuses will require leadership from male allies who reject misogynist norms and include women in both formal and informal power centers. Having more women in legislative leadership may be a necessary but insufficient step in establishing a more woman-friendly work environment. Women’s collective action can pressure their colleagues to change. For example, Texas State Representative Senfronia Thompson, flanked by her women colleagues, pointed out the role lawmakers have in shaping gender norms and expectations when in 2011, she shamed those who had circulated a political pamphlet depicting a woman’s breast as a metaphor for the nanny state, saying: “Lawmakers, as we are, have an opportunity to shape the attitudes of the public—and those attitudes can be positive toward women, they can be negative toward women, or they can be both. That falls within the gamut of all our possibilities.” Women face misogyny in all workplaces and can work with each other and men to create spaces that are more equitable. Legislatures can be leaders in establishing the standards of workplace environments that respect all workers and cultivate their potential.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2PNI7DS

About the author

Anna Mitchell Mahoney – Tulane University

Anna Mitchell Mahoney – Tulane University

Anna Mitchell Mahoney is an Administrative Assistant Professor of Women’s Political Leadership at Newcomb College Institute at Tulane University. Anna’s research focuses on women’s representation and gendered institutions, which she explores in her book, Women Take Their Place in State Legislatures: The Creation of Women’s Caucuses, due out this November with Temple University Press.