In past decades, senate and gubernatorial elections were determined more by the candidate and the state’s local politics than the national political climate. Joel Sievert looks at the continuing trend for statewide elections to become more nationalized, finding that in 2016, 90 percent of Senate contests and 74 percent of gubernatorial elections were won by the party that also carried the statewide vote.

In past decades, senate and gubernatorial elections were determined more by the candidate and the state’s local politics than the national political climate. Joel Sievert looks at the continuing trend for statewide elections to become more nationalized, finding that in 2016, 90 percent of Senate contests and 74 percent of gubernatorial elections were won by the party that also carried the statewide vote.

On Election Night 2018, Democrats and Republicans had reason to be both pleased and dissatisfied with the results of the US Senate elections. While Republican’s hopes of increasing their majority did not materialize, the party did manage to pick up several Democratic seats. Similarly, Democrats were no doubt disappointed about loses by some of their top challengers and vulnerable incumbents. Several Democratic incumbents did, however, perform well in key swing states—Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—that had been crucial for President Trump’s victory only two years earlier. In short, it was an election in which neither party made significant inroads, but also neither party was without some hope for the future.

In contrast, the outcome of the 2018 gubernatorial elections was, on average, far more encouraging for the Democrats. Prior to this election, around one-third of governorships were held by a Democrat. After strong performances from Democratic incumbents and challengers, the party now controls 23 of the 50 governor’s mansions. There were, however, at least a few positive results for the Republicans. Three popular Republican incumbents—Charlie Baker, Larry Hogan, and Phil Scott—held onto their seats in Democratic strongholds of Massachusetts, Maryland, and Vermont respectively. These victories were cancelled out, however, by both expected (e.g. Illinois) and more surprising (e.g. Kansas) Democratic gains.

“Blue Texas” by Dan Brekke is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

Despite the differences in partisan fortunes across senatorial and gubernatorial elections, the 2018 results were still largely consistent with the broader trend of more nationalized elections. As Dan Hopkins’ recent book outlines, elections can become more highly nationalized in several different ways. With respect to election outcomes, however, nationalization can be thought of in terms of an increased association between the outcomes of presidential and down ballot elections. The increased correspondence between presidential and statewide elections suggests that top-down forces, on average, have a greater impact on election outcomes than do candidate-specific factors or local conditions. In more nationalized elections, it is top-down forces, which may include presidential vote choice or partisan identification, that drive vote choice rather than factors like incumbency or candidate ideology.

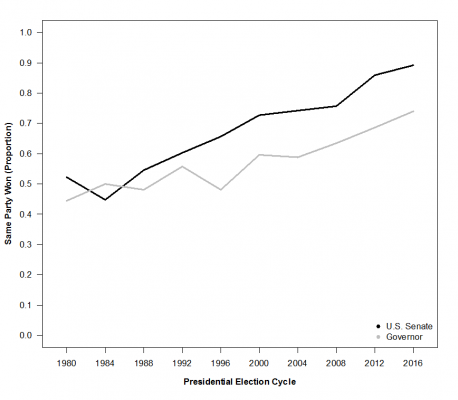

Figure 1, which tracks the relationship between the partisan outcome of both statewide and presidential elections over time, provides evidence of nationalization in both types of statewide elections. In the 1980s, between 45 and 55 percent of presidential and statewide down ballot elections resulted in the same party winning the statewide vote. During the 1990s and 2000s, the same party won the statewide vote in approximately 60 to 70 percent of senatorial and presidential contests. By contrast, the partisan similarity in gubernatorial contests remained below 60 percent until the late 2000s and early 2010s. During the 2016 election cycle, 90 percent of Senate contests and 74 percent of gubernatorial elections were won by the party that carried the statewide vote in the 2016 presidential election.

Figure 1 – Presidential and Statewide Elections Won by the Same Party

In addition to the clear upward trend in nationalization in senatorial and gubernatorial elections, there is also a notable difference between the two offices. Since the 1988 election cycle, gubernatorial elections have been less nationalized than races for the US Senate. During the 1988 and 1992 election cycles, the difference was around 5 percentage points, but increased to almost 18 percentage points by the 1996 election cycle. The gap between the two contests has remained in double digits, often around 15 percentage points, from the 2000 election cycle onward.

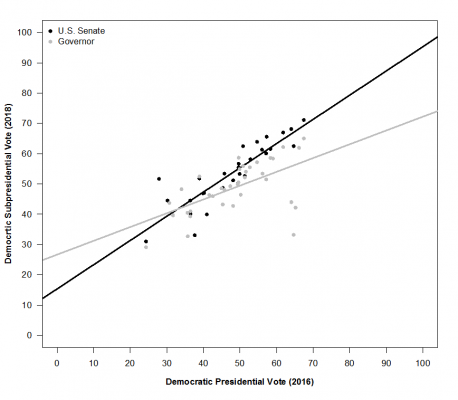

The greater insulation of gubernatorial elections from national forces was also evident in 2018. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the statewide vote in the 2016 presidential election and the 2018 gubernatorial (gray dots) and US Senate elections (black dots). For both contests, the 2016 presidential vote is positively correlated with the 2018 statewide vote. In order to help visualize these relationships, Figure 2 also includes the regression line from a regression model that uses the 2016 presidential vote to predict the 2018 US Senate (black line) and gubernatorial (gray line) vote. Based on this analysis, a Democratic Senate candidate could expect to receive around an 8-percentage point of the vote for a 10-percentage point increase in the party’s state-level presidential vote. By contrast, a Democratic gubernatorial candidate is predicted to receive only about 4.5-percentage points for a 10-percentage point increase in the party’s statewide presidential vote share.

Figure 2 – 2016 Presidential and 2018 Statewide Democratic Vote Shares

The high levels of nationalization in Senate elections shown in both Figures 1 and 2 is of particular note when looking ahead to the 2020 elections. Republicans will have to defend 22 Senate seats compared to the Democrats 12 seats. More importantly, the 2020 US Senate contests include Republican seats in some Democratic leaning states, such as Colorado and Maine, and states that have historically been competitive, like Iowa and North Carolina. While it is far too early to know if control of the Senate is likely to flip, the mix of a greater correspondence between presidential and senatorial elections and a relatively unfriendly US Senate map suggests that Republicans will have an uphill battle to retain their majority. Regardless of which party wins majority control of the Senate, it is reasonable to expect that they, like other recent Senate majority parties, will have to govern with a narrow majority.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Nationalization in U.S. Senate and Gubernatorial Elections’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ShfjmZ

About the author

Joel Sievert – Texas Tech University

Joel Sievert – Texas Tech University

Joel Sievert is an assistant professor of Political Science at Texas Tech University. Sievert studies congressional politics and elections, the presidency, and American political development. His research on congressional elections includes articles in Journal of Politics, Legislative Studies Quarterly, and a co-authored book, Electoral Incentives In Congress (University of Michigan Press 2018).