There is a growing tendency to link the policymaking preferences and decisions of elected representatives with the influence of interest groups, usually in the form of campaign contributions or lobbying. Using teachers’ unions as a case study, Leslie K. Finger finds that campaign donations are actually less important to the success of interest groups gaining influence than is widely believed. She writes that when teachers’ unions have higher membership rates, the power to elect allies means that they are more likely to get the policy outcome they desire from faithful legislators. Contributing to campaigns, on the other hands, does not.

There is a growing tendency to link the policymaking preferences and decisions of elected representatives with the influence of interest groups, usually in the form of campaign contributions or lobbying. Using teachers’ unions as a case study, Leslie K. Finger finds that campaign donations are actually less important to the success of interest groups gaining influence than is widely believed. She writes that when teachers’ unions have higher membership rates, the power to elect allies means that they are more likely to get the policy outcome they desire from faithful legislators. Contributing to campaigns, on the other hands, does not.

In the United States, we often attribute policymaking and political developments to the influence of powerful interest groups, whether shadowy corporations, “big labor,” or some other group that we assert is pulling the strings behind the scenes. We point to groups’ campaign spending or their lobbyists as evidence that they have power over policymakers. We then assume that most stances being taken by our elected representatives are being pushed by their special interest benefactors.

But lobbying and donating to campaigns are surface-level, short-term actions that may not capture which interest groups are powerful. Why lobby if your guys are already in the room writing the policy? Why donate to campaigns if the legislature is dominated by true-believing allies that will support your goals regardless of your pressure? It may be that the interest groups that shape the policy agenda before the debate even begins are the ones with the most influence.

Teachers’ unions are one of the most important membership-based interest groups in the US, and are a good case study for examining the source of interest group strength. They seek to influence policy through a variety of avenues including with campaign contributions, lobbyists, electoral mobilization, etc. Are their donations to campaigns as important to their success as the popular imagination would predict? It turns out the answer is no; dynamics that are less visible matter more.

What do we know about interest group influence?

In the public debate, we assume that interest group lobbyists “purchase” legislators’ votes on particular bills. While interest groups certainly lobby and contribute to political campaigns, there is little evidence that either activity allows interest groups to move policymakers’ opinions or influence policy. Still, interest groups believe that their donations help. It may be that contributions give interest groups access to policymakers or get them to spend time on issues that matter to interest groups, if not specific voting outcomes. As to lobbying, opposing interest groups likely cancel out each other’s efforts.

If lobbying and donating to campaigns don’t give interest groups influence over policy, what does? In a famous paper published in the 1960s, two scholars conceived of two types of power—one that is exercised once issues are already on the table and the other that comes about through decisions made before the debate begins. Those with the former focus on persuading their opponents, while the latter can set the agenda, meaning that persuasion is unnecessary since the issue never reaches the state house floor.

What might these types of power look like for interest groups? Interest groups do not directly make legislative decisions; rather, their policy maker allies do. Therefore, where interest groups have allies in control of the legislature, they will be able to safely assume that their interests will be reflected in the agenda. The name of the game, then, is determining who is in the room and, better still, who sets the agenda in that room.

Assessing two types of interest group power

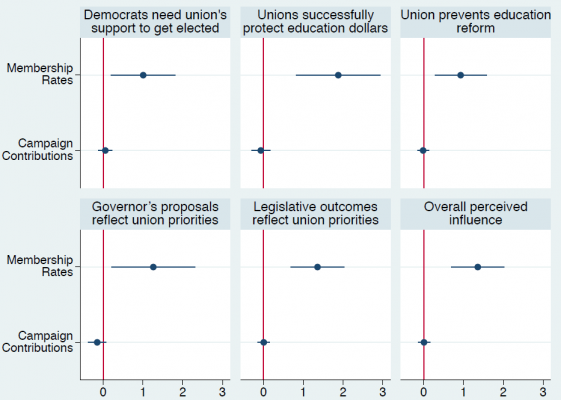

Because interest groups with higher membership rates reflect a greater number of voters, and more voters means the election of more allied legislators, teachers’ union membership rates are related to their ability to set the policy agenda; more members means more allies in office determining the terms of the policy debate. If being able to determine who has a seat at the table leads to more influence on policy than surface-level, short-term behaviors like donating to campaigns, teachers’ unions membership rates should be positively related to stakeholder’s candid assessments of their influence, whereas campaign contributions should not. An analysis using the Fordham Institute’s survey of stakeholders across all 50 states bears out this pattern.

“Chicago Teachers Union Members and Allies Picket Outside Chicago Public Schools Headquarters Downtown Chicago Illinois 9-26-18 4119” by Charles Edward Miller is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Figure 1 shows that, when controlling for state partisanship and the presence of education reform groups, where teachers’ unions have higher membership rates, stakeholders surveyed perceive them to be more influential; the dot represents the size of the relationship between each measure of power and stakeholders’ agreement with the statement at the top of each subfigure. Teachers’ unions with higher memberships were deemed to be more important to the success of Democratic candidates, more able to protect education dollars, even during recessions, and more able to prevent adverse education reform policies. Governors’ policy proposals and passed legislation were more likely to reflect teachers’ union priorities. In stark contrast, there is no such relationship for campaign contributions, as is clear by the bottom row dot overlapping with the red vertical line. This suggests that groups that donate more do not necessarily have more of a say in policymaking.

Figure 1 – Membership rates, not campaign contributions, are positively related to perceptions of influence

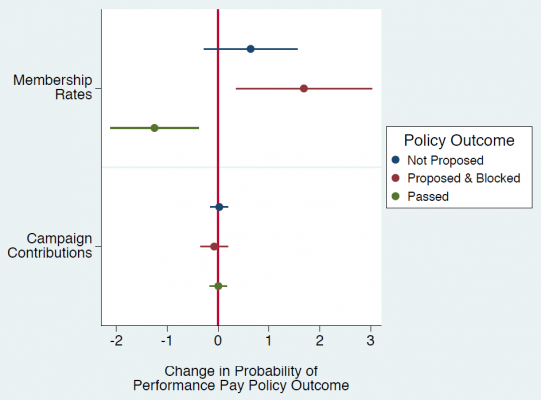

But do these different types of power also shape policy outcomes? One policy that should spur teachers’ unions to mobilize is merit pay, meaning the rewarding of salary increases to teachers for gains in student achievement. There is evidence that merit pay is among the policies that teachers and their unions most strongly oppose.

I analyze the relationship between merit pay bill outcomes and the two measures of power using data on merit pay policies across all 50 states between 2011 and 2016. This was in the wake of the Obama administration’s 2010 Race to the Top program, which incentivized such policies. For each state, I recorded the final outcome of the merit pay bill that went furthest in the legislative process during this period using LegiScan and the Education Commission of the States.

Figure 2 shows the relationship between teachers’ union membership rates and campaign contributions and the following three outcomes: whether any performance pay bill was proposed at all, if it was proposed, whether it was blocked, and whether any performance pay bill passed. Figure 2 shows that, across all three policy outcomes, where teachers’ unions have higher membership rates, they are more likely to get their desired policy outcomes. Not so for campaign contributions.

Figure 2 – Membership rates, not campaign contributions, are related to policy outcomes

Interest group strength is about allies – not contributions

Despite the narrative of big campaign spenders and lobbyists controlling politics in the United States, interest group strength comes from having legislative allies setting the policy agenda. In fact, it is likely that contributions are often defensive. Take the National Rifle Association (NRA). If groups are most influential where they spend the most, one might assume that the NRA spends the most in conservative, pro-gun states. In fact, according to National Institute on Money in Politics, the group spends the most in battleground and blue states, such as Colorado, Washington, California, and Nevada. This is likely because the group already has the ability to set the agenda in the most conservative states through a large number of allies in the legislature and instead focuses funds where its influence is more tenuous.

Scholars and pundits should take heed that what often appears to be the origin of interest group strength may in fact reflect defensiveness or be supplementary to what is the real source of power – having allies setting the agenda. Just because power is less visible does not mean it’s not there.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Interest Group Influence and the Two Faces of Power’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2Ua2cG0

About the author

Leslie K. Finger – Harvard University

Leslie K. Finger – Harvard University

Leslie K. Finger is a lecturer on government and social studies at Harvard University. Her research focuses on interest group influence and the politics of education.