After lengthy battles over a Continuing Resolution to fund the U.S. government, Congress has failed to reach an agreement, and the government is now in the process of shutting down. Michele Swers looks at how and why these budget fights have become a familiar part of Congressional politics in America. She argues that the increasing ideological polarization of the Republican and Democratic parties is a major contributor to their inability to bridge policy divides. This is exacerbated in that most members of Congress represent seats that are very safe for their party, meaning that they are more afraid of losing to an ideologically extreme primary challenger than suffering a defeat in an election.

After lengthy battles over a Continuing Resolution to fund the U.S. government, Congress has failed to reach an agreement, and the government is now in the process of shutting down. Michele Swers looks at how and why these budget fights have become a familiar part of Congressional politics in America. She argues that the increasing ideological polarization of the Republican and Democratic parties is a major contributor to their inability to bridge policy divides. This is exacerbated in that most members of Congress represent seats that are very safe for their party, meaning that they are more afraid of losing to an ideologically extreme primary challenger than suffering a defeat in an election.

Once again Congress and the President are locked in a tense battle over the budget with the government now in the process of shutdown and a potential default on the national debt coming as soon as October 17. Since Republicans won control of the House of Representatives in 2010, the Republican House and President Obama have engaged in continuous fiscal showdowns over the size and scope of the federal government and the future of entitlement programs. This crisis is unfolding against the backdrop of the Great Recession and historically high deficits. Why do these budget fights occur?

One contributing factor is divided government, of which policy gridlock is a common feature. When President Obama and Democrats controlled the executive and the legislative branches, they were able to pass several major pieces of legislation, most notably the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) and the Dodd-Frank banking reform bill. However, once Republicans won the majority in the House, major legislative initiatives outside of the budget process, such as the push for immigration reform, stalled. Research indicates that gridlock becomes worse when the ideological distance between the House and Senate increases and when there are fewer moderates to broker deals between the two parties. The ideological distance between the Democratic-controlled Senate and the Republican House is particularly vast and the exodus of the remaining moderates continues.

Given the high levels of gridlock in Congress, the must-pass elements of the annual budget process (Continuing Resolutions, Omnibus Appropriations, and raising the debt ceiling) become the prime avenues for each party to try to achieve its legislative priorities. Over time, the majority party in Congress has often used these must-pass bills to gain leverage over the President and force policy concessions. What makes the current crisis so dangerous is the high levels of polarization in Congress and the politics of Obamacare.

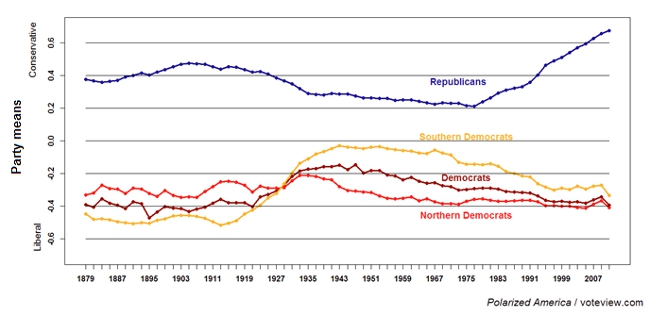

A major contributor to the inability of Republicans and Democrats to bridge policy divides is the increasing ideological polarization of the two parties. With the realignment of the solidly Democratic south to the Republican Party, the party elites and their voters have been sorting themselves into a more uniformly liberal Democratic Party and a more uniformly conservative Republican Party. As Figure 1 below from Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal’s research on voting patterns of members of Congress demonstrates, the governing philosophies of the two parties have continued to diverge over time Additionally, while Democrats have clearly become more liberal, Republicans have moved toward higher levels of conservatism beginning in the Reagan years and after the Republican Revolution in 1994 that ushered in Republican control of Congress for the first time in 40 years.

Figure 1 – Party polarization in the House 1879-2012

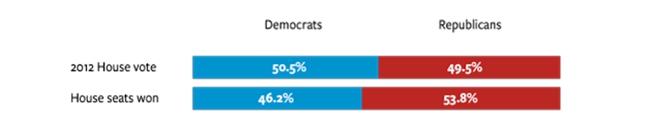

The race to the extremes is reinforced by aspects of the electoral system including the redistricting process, party primaries, and developments in campaign finance. The Republicans’ electoral victory in Congress and the state legislatures in 2010 allowed them greater control over the redistricting process for 2012 and the ensuing 10 years. While the tendency of voters to cluster in like-minded communities means partisan gerrymandering has its limits, Republicans did win the majority of House seats in 2012 while losing the national congressional vote, as Figure 2 illustrates.

Figure 2 – House votes and seats won in 2012 elections

Source: National Journal, David Wasserman, “Why Republicans Have a Lock on the House.” Dec. 2012

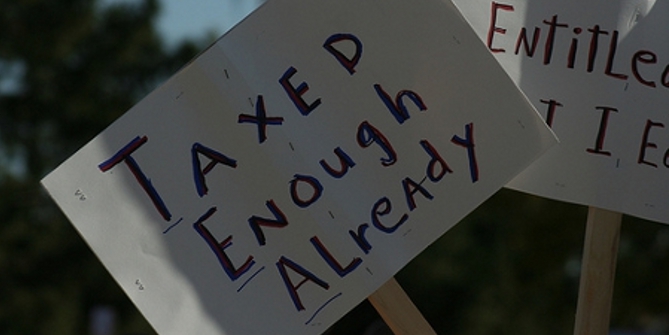

The fact that most members of Congress represent seats that are very safe for their party means that legislators are more afraid of losing to an ideologically extreme primary challenger than suffering a defeat in the general election. The threat of a primary challenger gives more power to the extreme voices in the Republican Party such as the tea party that are pressuring Republican leaders and the rank and file to defund Obamacare even if it requires a government shutdown or breach of the debt ceiling. Campaign finance law provides these groups with more power to solicit unlimited sums from wealthy individuals committed to an ideological cause. Super PACs (Political Action Committees) and other groups raise unlimited funds to finance issue ads against candidates who don’t fight government spending. As the House Republican caucus becomes more conservative, these members have made it clear to their party leadership that they will not vote to support continued government funding without fundamental policy changes, including cuts in government spending and elimination of Obamacare.

Since the House is a majoritarian institution, Speaker Boehner could turn to the Democrats to help find a majority of votes to pass the budget. Boehner has relied on Democrats to pass major fiscal legislation in the past including the 2011 Budget Control Act to end the debt ceiling crisis, the 2012 Omnibus Spending bill, and most recently the January 2013 fiscal cliff deal that increased taxes on top earners and briefly delayed the sequester. However, he continues to promise to follow the “Hastert Rule” to only pass bills that have the support of a majority of the majority. Boehner faced a challenge to his speakership at the beginning of the current Congress and could lose the support of his caucus if he were to try to pass a bill with Democratic votes.

Finally, electoral competition and the politics of Obamacare have increased the stakes for both sides. Republicans continue to add on policy riders seeking to chip away at aspects of Obamacare by defunding it, delaying it, or stripping particular provisions because it is a fundamental issue for their party base. Republicans swept into power in 2010 on a tea party wave in which Obama and the Democrats lost a record 63 seats and their House majority partially because of conservatives’ anger over Obamacare. Similarly, Bill Clinton lost 54 House seats and majority control as Republicans capitalized on anger over Clinton’s failed efforts to pass national health insurance reform.

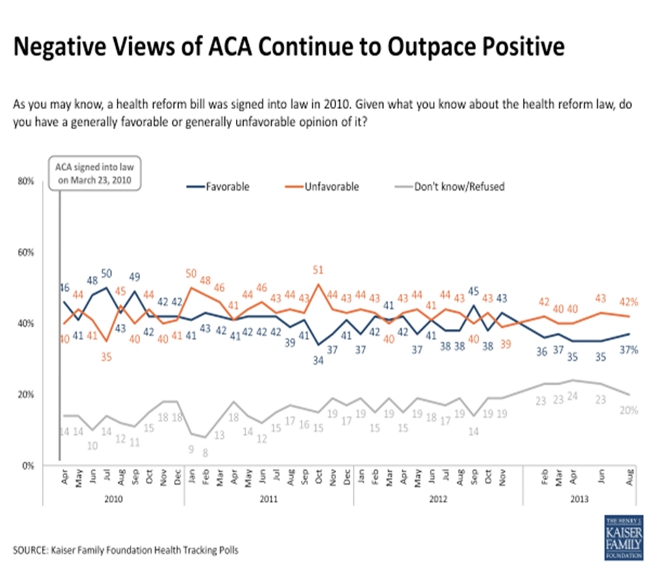

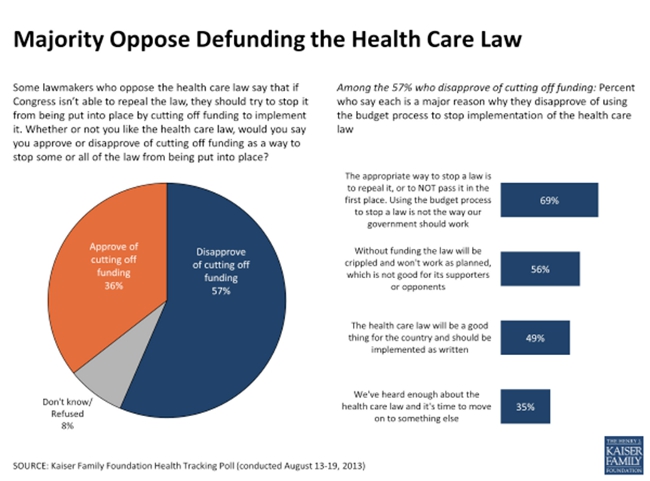

Since the 1990s, electoral competition has remained tight and each side sees the possibility of securing the majority in Congress. Republicans hope to capitalize on the fact that since its passage, Obamacare has remained unpopular with the public. Polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation demonstrates that support for the law remains below 50%, as shown in Figure 3. Yet Americans are also opposed to defunding the law, as Figure 4, below, illustrates. As the health care exchanges and other major provisions of the law quickly come online, Republicans view the current budget battles as the last chance to reverse course and prevent the Affordable Care Act from becoming an entrenched part of the American health care system like Medicare and Medicaid.

Figure 3 – Views on the Affordable Care Act

Figure 4 – Opposition to defunding the Affordable Care Act

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1dTC7jD

_________________________________

Michele Swers – Georgetown University

Michele Swers – Georgetown University

Michele Swers is an Associate Professor of American Government in the Department of Government at Georgetown University. Her research interests encompass Congress, Congressional elections, and Women and Politics. Her most recent book, Women in the Club: Gender and Policy Making in the Senate (University of Chicago Press 2013) examines the impact of gender on senators’ policy activities in the areas of women’s issues, national security, and judicial nominations.

2 Comments