In Standing Rock: Greed, Oil and the Lakota’s Struggle for Justice, Bikem Ekberzade draws on the voices of Native American protesters to offer an account of their experiences of contesting the rerouting of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) close to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. Contextualising the protest through an attentiveness to the historical injustices that continue to impact upon Native cultures and lives, this is a thoughtful, engaging and moving book, writes Rikki Oden.

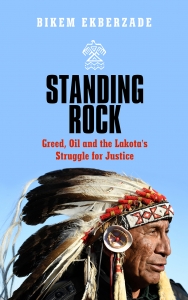

Standing Rock: Greed, Oil and the Lakota’s Struggle for Justice. Bikem Ekberzade. Zed Books. 2018.

Bikem Ekberzade’s Standing Rock: Greed, Oil and the Lakota’s Struggle for Justice tells the moving story of Native American protesters during the 2017 conflict surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), and dives into condemning detail of the US federal government’s treatment of the tribes both during the protests and historically—injustices which strongly influence Native American culture and issues to this day. Ekberzade brings new light to these cumulative and continuous transgressions with detailed personal accounts of colonial persecution across centuries, allowing untold insight into the emotions and motivations of the Native tribes and non-Native environmentalists that joined together in protest of the DAPL.

The original planned route for the DAPL would bring the pipeline in close proximity to municipal water sources and residential areas of the primarily white town of Bismark, North Dakota, and was thus rejected. The protests at Standing Rock Sioux Reservation began in October 2014 in response to the Army Corps of Engineers’ decision to reroute the pipeline underneath the Missouri River just half a mile from the Standing Rock Reservation, endangering local water resources and destroying hundreds of sacred Native American sites, including burial grounds. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe filed a lawsuit challenging this decision, but the tribe was unsuccessful in its legal attempts to stop the pipeline construction, though they followed political procedures to voice their environmental concerns. National awareness of the injustice faced by the Reservation gained global attention through the use of the hashtag #NoDAPL as people from across the US and around the world joined the protest camps. The protesters—who identified themselves as ‘water protectors’—faced harsh winter conditions and violent counterterrorism tactics by both the US government and a private security company as they fought for the protection of the sacred land. Despite the immense efforts of the water protectors, the camps were eventually cleared out and the pipeline completed.

This monograph marks a shift in format for the Turkish frontline journalist and author Ekberzade, who has previously published multiple photo books and documentaries focused on refugees, including The Refugee Project. As part of her commitment to covering social justice across the globe, she began research on Native Americans and the Standing Rock conflict in 2016, interviewing key activists, public officials and historians for the project. The resulting book contains four chapters. It recounts—from their point of view—the challenges that the Tribal Nations face today and how this conflict ultimately culminated in the standoff at Standing Rock.

Image Credit: Camp Red Fawn, Oceti Sakowin Camp, Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, North Dakota (Becker1999 CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: Camp Red Fawn, Oceti Sakowin Camp, Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, North Dakota (Becker1999 CC BY 2.0)

In the first chapter, we are introduced to the people who make up the resistance movement and are given background information on the history of Native and federal conflicts. The author details injustices like the Dawes Act of 1887, which enabled the federal government to break up tribal lands into individual plots under the guise of giving Native Americans valuable individual land ownership and citizenship. It was an attempt to assimilate Native peoples into mainstream US culture by removing them from core traditions of communal land ownership and implementing required taxes on land their families had tended to and lived on for thousands of years.

The second chapter, entitled ‘Seventh Generation’, highlights several key women who initiated the DAPL resistance movement: the most notable being La Donna Brave Bull Alard of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. On 1 April 2016, LaDonna opened Sacred Stone, one of the water protector camps, which ran on green energy and held the goal of becoming a sustainable community. La Donna’s daughter, Prairie McLaughlin, designated herself as a watchdog for the ongoing DAPL oil and gas meetings, as well as any resulting legislature changes. Her diligence in passing along information to key Native American activists allowed the coming injustices to be brought to light. During the protests, Prairie was arrested and spent a night in jail, where she said she enjoyed her first hot shower in weeks and ‘slept like a baby’—a stark contrast to the freezing conditions protesters faced within the camps while they determinedly fought against the pipeline.

Bobbi Jean Three Legs, another Native protester, ran thousands of miles carrying messages to faraway tribes and federal government leaders, drawing the attention of the world’s media. At a smaller (but no less significant) scale, Julie Garreau and Tammy Joy Granados focused on enabling youth to help themselves at the Cheyenne River Youth Project (CRYP). The goals of this ongoing project are to help local youth break cycles of poverty, suicide and addiction. Here, Ekberzade introduces the concept of postcolonial stress—a term which is used to refer to the feelings of grief and helplessness experienced by Native American children, leaving them less resilient in the face of issues like depression and other mental health problems. By providing a space for Native youth to interact with each other and the supervising adults, the CRYP hopes to improve lives and the continued future of Native American culture. Julie’s dream is for the youth she serves to feel that being Lakota is a natural part of them: ‘You know, just like getting up and getting dressed: being Lakota. That’s a natural part of who they are too.’

The third chapter of the book provides information on land-grabbing techniques exercised by the federal government, and on pipelines similar to the DAPL, comparing them to the Lakota prophecy of a black snake that would desecrate the land and destroy its natural resources. The colonialist idea that all Native American tribes are one lump group—‘Indians’—is a mentality LaDonna objects to, saying ‘there is no Native American culture. There are native people with many cultures. Many languages.’ Despite constant pushback by individual Native groups against this mentality, mainstream thinking in the US continues to view tribes as a monoculture and contributes to the dismissive attitude they repeatedly receive from public and private development groups who want to use land for their own purposes. With each new pipeline project that ignores the values of local tribes, the black snake slithers across the land, continually defiling these sacred sites.

‘The Showdown at Standing Rock’ is the culminating chapter which drives home the importance of the protest. The water protectors at Standing Rock and the people who brought them together demonstrate a shift in Native American culture today. Tradition dictates that the elders lead the tribes and make key decisions, but in this instance it was the youth who brought the larger movement to life. This approach enabled the protests to grow into something particularly special: the protesters’ self-described tactics of non-violent direct action were inherently coupled with a lifestyle that was the least disruptive to nature. The Cherokee, Sioux, Dine and more stood together in:

a protest that was not only calling an end to centuries of exploitation but also reminding the world what was most sacred and most necessary for our survival: water. What was occurring at Standing Rock was bigger than what went on at Wounded Knee, bigger than any of the battles the Native Americans fought against white oppression. What was going on at Standing Rock was universal.

With powerfully moving personal accounts, this book achieves its purpose in educating non-Native people in the US and across the globe on decades-old injustices and their influence on the Standing Rock protests. Ekberzade’s writing is both thoughtful and engaging: a description of young water protectors charging horses against police vehicles inspires courage, bravery and determination in fighting for a cause—the kind that the world could use more of in its environmental advocates today.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2VUnxYe

About the reviewer

Rikki Oden – Portland State University

Rikki Oden is a graduate student at Portland State University studying flooding issues in Tillamook, Oregon, with a focus on the conflict and collaboration between wetland restoration and agricultural communities. Rikki’s interest lies in water policy of the Western United States, as well as water justice both close to home and across the globe.

Find this book:

Find this book: