American politics is typically a story about winners. The fading away of defeated politicians and political movements is a feature of American politics that ensures political stability and a peaceful transition of power. But American history has also been built on defeated candidates, failed presidents, and social movements that at pivotal moments did not dissipate as expected but instead persisted and eventually achieved success for the loser’s ideas and preferred policies.

In their book, Legacies of Losing in American Politics, Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow rethink three pivotal moments in American political history: the founding, when Anti-Federalists failed to stop the ratification of the Constitution; the aftermath of the Civil War, when President Andrew Johnson’s plan for restoring the South to the Union was defeated; and the 1964 presidential campaign, when Barry Goldwater’s challenge to the New Deal order was soundly defeated by Lyndon B. Johnson. In each of these cases, the very mechanisms that caused the initial failures facilitated their eventual success. But after the dust of the immediate political defeat settled, these seemingly discredited ideas and programs disrupted political convention by prevailing, often subverting, and occasionally enhancing constitutional fidelity. Tulis and Mellow present a nuanced story of winning and losing and offer a new understanding of American political development as the interweaving of opposing ideas.

In their book, Legacies of Losing in American Politics, Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow rethink three pivotal moments in American political history: the founding, when Anti-Federalists failed to stop the ratification of the Constitution; the aftermath of the Civil War, when President Andrew Johnson’s plan for restoring the South to the Union was defeated; and the 1964 presidential campaign, when Barry Goldwater’s challenge to the New Deal order was soundly defeated by Lyndon B. Johnson. In each of these cases, the very mechanisms that caused the initial failures facilitated their eventual success. But after the dust of the immediate political defeat settled, these seemingly discredited ideas and programs disrupted political convention by prevailing, often subverting, and occasionally enhancing constitutional fidelity. Tulis and Mellow present a nuanced story of winning and losing and offer a new understanding of American political development as the interweaving of opposing ideas.

We asked three academic experts on American political history and theory to review Legacies of Losing in American Politics: Richard J. Ellis of Willamette University warns that the Democratic Party could learn the wrong lessons from the three ‘losers’; Sidney Milkis of the University of Virginia finds that the book supports the idea that the US has no clear cultural or constitutional direction; and UCLA’s Steven Bilakovics writes that while we revere winning, we also resent the winners. In their response, Mellow and Tulis note that while all of the critics are thoughtful, insightful, and provocative, some of their views evidence, rather than rebut, the central thesis of the book.

Jump to…

-

Richard J. Ellis (Willamette University): “Losing is a luxury that only the Right can afford in US politics”

-

Sidney Milkis (University of Virginia): “Legacies of Losing raises as many questions as it answers”

-

Steven Bilakovics (UCLA): “The purported losers of the transformational contests should not be considered mere footnotes to history”

-

Authors’ Response: Jeffrey K. Tulis (University of Texas at Austin) and Nicole Mellow (Williams College): “Our critics’ thoughtful observations provide a richer understanding of our argument, its possibilities and its limitations.”

Richard J. Ellis: “Losing is a luxury that only the Right can afford in US politics”

Speaking at a commencement address in May 2018, President Trump told the newly minted graduates of the Naval Academy that there is “nothing like winning — you got to win. . . [T]hat is what it is all about.” Trump is hardly alone in celebrating winning and lionizing the winners. None of us want to be losers. We all prefer that “great feeling” of winning to the agony of defeat.

It turns out, though, that in politics at least, telling the winners from the losers is more difficult than Trump would have us believe. If Jeffrey Tulis and Nicole Mellow are right, those who seem at the time to be losers sometimes end up as history’s biggest winners. From that simple premise, Tulis and Mellow offer a nuanced history of the “legacies of losing” in the US that profoundly challenges the way we think about three of the great losers of American politics: the Anti-Federalists, Andrew Johnson, and Barry Goldwater.

There is much to praise about Legacies of Losing in American Politics, starting with the grace and clarity and succinctness of the writing. Each of the three core historical chapters are sophisticated, learned, and provocative, particularly the analysis of Andrew Johnson, which is one of the best and most unsettling things I’ve read on the nation’s 14th president. But rather than heap deserved praise upon this important book, I will focus on a couple of my reservations about their argument—and the implications of the argument for our understanding of American political history.

I share Tulis and Mellow’s premise that we have only had one regime, and that analyses (Bruce Ackerman’s, for instance) that focus on refounding moments understate the continuities of American political culture, which has at its core an individualism and antistatism that has persisted with extraordinary resilience despite the creation of the Union and ratification of the Constitution, Radical Reconstruction, and the New Deal. Recognizing the enduring power of America’s liberal and antistatist political culture, however, leads me to suggest that we may need to rethink a couple key components and conclusions of Legacies of Losing.

Resetting to the Anti-Statist Default

Specifically, I wonder whether the phenomenon being described by Tulis and Mellow is less a generalizable argument about the “legacies of losing” than it is a description of the ways in which the United States, following a transformative moment, then resets to the anti-state default of American political culture. That is, we need to ask whether the short-term loss turned into a longer term victory because of the loss or whether the aftermath of the loss is better understood as a reversion to the default cultural condition of US politics: anti-statism.

It’s impossible to ignore that what each of these three losses have in common is anti-statism, or what political scientist Louis Hartz called Lockean Liberalism and Samuel Huntington called the antipower ethic of the American Creed. Not one of the three examples of the legacies of loss is from a state-building “antimoment.” Tulis and Mellow write that: “Winning might not always be preferable to losing,” but what if this is only true for the antistatists? The antistatists, in other words, are in a win-win situation. They win when they lose and they win when they win.

After all, had the Anti-Federalists won, wouldn’t Anti-Federalist anti-statism have become stronger still? And had Andrew Johnson won, wouldn’t anti-statism and white supremacy have been stronger still? Only with Goldwater does it seem plausible to argue that a win might have made for a less robust conservatism because there would have been no Voting Rights Act or at least no Great Society and War on Poverty—and hence no conservative backlash to bring Robert Reagan to power.

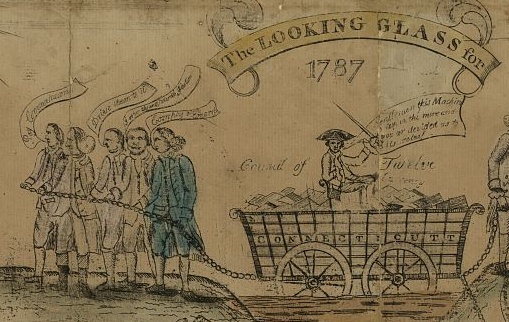

The looking glass for 1787. A house divided against itself cannot stand. Mat. chap. 13th verse 26 Credit: Library of Congress

It seems to me that the most parsimonious answer to Tulis and Mellow’s puzzle—“How . . . ideas and policies rejected as part of a moment of constitutional refounding remerge, are endorsed and have impact…”—is that Lockean liberalism and the antipower creed have extraordinary staying power, so that efforts to dislodge them are only temporarily successful. Looked at in this way, the “winning” legacies of Tulis and Mellow’s three “losers” are less surprising.

Let’s take the three cases in turn:

Tulis and Mellow’s persuasive story of the Anti-Federalist “politics of appropriation” is profoundly important in getting us to think about how what they call “the political heirs of Anti-Federalism” were successful in transforming the Constitution from a state-building document into an anti-statist document. And they are surely right that in profound and underappreciated ways Americans of all political stripes have bought into this Anti-Federalist reinterpretation of the Constitution. But is the fact that Federalists needed to play up the anti-power elements of Constitution a tribute to Anti-Federalist agency or to the enduring power of anti-statist views and the Federalists’ resulting need to cloak their state-building ambitions in anti-power rhetoric? It is telling, I think, that this chapter devotes relatively little to Anti-Federalist agency; it is instead mostly about the Federalists’ agency, particularly their rhetorical strategy, a strategy dictated by the strong anti-power creed of American political culture.

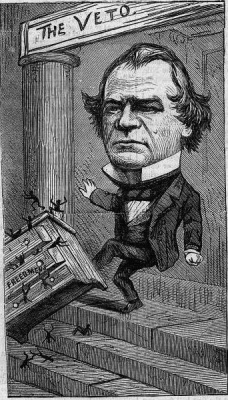

Unlike in the Anti-Federalist chapter, in the Johnson chapter Tulis and Mellow focus great attention on the loser’s agency. And it’s a tribute to this chapter that I will never think about Johnson in quite the same way. The Johnson that emerges here is a much more consequential and successful figure—if still utterly repugnant—than I and I think most historians and political scientists have reckoned.

But this chapter is vulnerable to a criticism similar to the one I leveled against the Anti-Federalist chapter. Is it really the case that Johnson’s loss “enabled the long term and lasting success of his vision” or was Jim Crow more or less inevitable given the weakness of the American state and strength of localism and suspicion of central government (not to mention virulent racism). Did Johnson’s vision succeed in other words despite rather than because of his ham-fisted efforts and incendiary rhetoric? And could a more rhetorically nuanced and politically skilled Johnson have brought about the same result even earlier? Surely, had Johnson won rather than lost, the legacy would have been an even quicker establishment of Jim Crow and anti-statism.

Tulis and Mellow acknowledge that “it is very possible that southern politicians would have deployed an arsenal of preemptive and obstructionist practices in their attempt to delay or defeat civil rights legislation without Johnson’s leadership.” But this concession is undercut by a string of causal claims advanced in the subsequent pages. For instance, they assert that “the forces of racial reaction had the opportunity to reemerge because of Johnson’s early and sustained leadership” (emphasis added). Later they write that “his imprimatur resuscitated [this constitutional interpretation of states’ rights] from the obscurity to which it might rightly have been destined given the South’s military defeat.” And then, most strongly of all, they comment that: “This particular ‘reassociation’ of national liberal ideas with regional purposes would not have been possible without Johnson’s initial ideological groundwork in the face of Congressional Reconstruction.” These claims greatly understate the power of racism and anti-statism—and the weakness of the American state—that made the failure of Reconstruction and reestablishment of Jim Crow as close to an inevitability as one can get in human affairs. It is not only “very possible” that Southern politicians would have deployed an arsenal of preemptive and obstructionist practices in their attempt to delay or defeat civil rights legislation without Johnson’s leadership; it’s a virtual certainty.

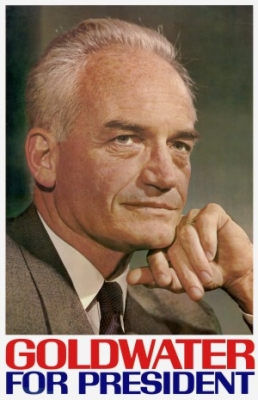

Finally, what about Goldwater? Did his “politics of integrity” enable the Republicans’ eventual repudiation of New Deal regime? Here I think Tulis and Mellow’s case is strongest since it seems quite plausible that a Goldwater win might have resulted a less potent conservative movement long term because liberalism would never have had the opportunity to push through the Great Society and War on Poverty that provoked a conservative backlash. But even where their case is strongest, there is a powerful counter case, as historian Jefferson Cowie argues in The Great Exception, that the New Deal was an exception that put into place institutions and policies that were at odds with underlying American political culture. From this perspective, the post-Goldwater Republican Party is largely a snapping back to the default condition of American politics. Looked at this way, as Cowie writes, “conservative achievements seem all the more inevitable and postwar liberal economic victories seem all the more extraordinary” (29). While it is important to recognize and credit individual agency, we should be careful not to lose sight of the powerful cultural currents of antistatism (and racial antagonism) within which these individual actors moved.

Learning the Wrong Lessons

If Goldwater is where I find the argument the strongest empirically, it is also where I find it most worrying. My concern is that liberal Democrats could learn the wrong lesson from Goldwater’s loss and that the enticing prospect of “legacies of losing” may be used to justify an ideological rigidity that may lead not only to short-term loss but a long-term one as well, a danger that Tulis and Mellow fully recognize. Not every loss has a positive legacy like Goldwater’s.

The danger is that Legacies of Losing will be (mis)read by activists to justify the “practice of political integrity” as opposed to the practice of traditional politics, that losing political contests in the moment will be justified by the promise of winning big in the future. In the antistatist political culture of the US, however, losses for the Left are less likely to lead the movement into the Promised Land than to march it into irrelevance. In the Hartzian world in which we live, the state builders of the Left cannot afford to believe that they can model themselves on the anti-statist Right. Put most baldly (and maybe badly), losing is a luxury that only the Right can afford in US politics. For the Left there are, literally in this book, no legacies of losing.

Getting right with Hartz

This leads me to my larger theoretical bone to pick with the authors: namely that Tulis and Mellow, despite their insistence that we have only ever had one regime don’t in the end do full justice to Hartz. In my view, far too much time is spent getting right with Rogers Smith and the “multiple traditions thesis,” when in fact Tulis and Mellow’s three antimoments are a chilling affirmation of the Hartz thesis. The lesson I take from this book is not the Smith thesis that the illiberal tradition hampers aspirations for greater equality but instead the Hartzian thesis that Lockean liberalism itself impedes those aspirations.

Tulis and Mellow’s reading of Hartz is far too sunny for my tastes. They equate a Hartzian view with the “conventional narrative of liberal progress and consensus” and a progressively fuller realization of liberalism and equality of rights. But Hartz’s vision is much darker, indeed tragic, than that. It’s closer to a suffocating Lockean hegemony than a happy liberal consensus. Properly understood, Legacies of Losing provides a powerful corollary to Hartz: We are imprisoned within a Hartzian liberal consensus—so that even when Hartzian liberalism loses in the short term, it wins in the long run. That, sadly, is how hegemonic power works.

About the reviewer

Richard J. Ellis – Willamette University

Richard J. Ellis – Willamette University

Richard Ellis is Mark O. Hatfield Professor of Politics, Policy, Law, and Ethics at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon. He has written widely on the history of the American presidency and American political culture. His recent books are a third edition of The Development of the American Presidency (Routledge, 2018), Historian in Chief: How Presidents Interpret the Past to Shape the Future (University of Virginia Press, 2019, co-edited with Seth Cotlar), and Old Tip vs. the Sly Fox: The 1840 Election and the Making of a Partisan Nation (University Press of Kansas, forthcoming 2020)

Sidney M. Milkis: Legacies of Losing raises as many questions as it answers

Jeffrey Tulis and Nicole Mellow have written a brilliant book that offers an entirely fresh interpretation of American political development; one that provides a comprehensive overview of how the losers of America’s most important constitutional moments have contributed – almost as much as the winners — to “regime change.” Tulis and Mellow are not the first scholars to focus on the importance of losers – and there have been many accounts of the enduring importance of the Anti-Federalists and Barry Goldwater’s failed 1964 presidential campaign. But their analysis of “self-transforming failure” – their braiding of the most important “constitutional moments” and the resistance to these transformative eras (“antimoments”) — offers a new interpretation of what success and failure mean in American politics.

Their main argument is that there is no one single intellectual battle that resolves the most fundamental contests in American political history. Rather, the fight for America’s constitutional soul persists in fits and starts, circumscribing, if not entirely preempting the legacies of the ratification of the Constitution, the Civil War and the New Deal. The inconclusive nature of these major developments sheds new light on the “multiple tradition thesis,” most prominently rendered by Rogers Smith. Following Smith, the authors argue that Liberal and Illiberal forces – liberal and exclusionary traditions – compete to define the character of the nation and the scope of citizenship. Tulis and Mellow view the enemies of Liberalism as more insidious, however: they lose, but under the guise of constitutionalism, these underdogs preempt and obstruct the Constitution’s “natural” course.

The chapter on Andrew Johnson is the most impressive of the three cases. There have been many accounts of Reconstruction’s implosion. But most scholars attribute the defeat of the Radical Republicans’ program to the bitter sectional standoff that led to the notorious “Compromise of 1877,” and, ultimately, to the onset of the Jim Crow regime during the 1890s. No interpretation of this post-war tragedy attributes so much “agency” to Andrew Johnson. Turning Stephen Skowronek’s story of reconstructive presidents on its head, Tulis and Mellow show persuasively that by forcefully representing Southern interests, Johnson changed the trajectory of the Civil War and the Constitutional amendments that followed in its wake. Radical Republicanism was not doomed by intractable sectionalism; rather, it was waylaid by him as the only Southern member of Congress who sided with the Union – a wolf in sheep’s clothing, as it turned out, for Johnson proved to be a clever demagogue who flattered the prejudices of his followers to betray the interests of the freedmen.

For all its virtues, as is the case with any ambitious book, Legacies of Losing raises as many questions as it answers. There are two, in particular, that puzzle me. First, I am not sure what the authors mean when they claim their “account is sufficient …to show that American political development has a constitutionally induced direction” (148). To the contrary, their story, I think, lends support to Rogers Smith’s argument that there is no clear cultural or constitutional direction in the United States. The authors’ depiction of the Anti-Federalist’s legacy suggests how the Constitution is hotly contested from the start. Moreover, the broad phrasing of the Constitution (and the complex institutional arrangements it created) allowed for a fundamental struggle over its meaning. In fact, the key constitutional moments of the Jeffersonian and Jacksonian eras (the latter is completely ignored in this book) reveal that the Anti-Federalists were not losers. Indeed, their vision of America as an imperfect Union composed of many communities prevailed until the New Deal and reverberates through our own political time. Along the way, many champions of full-throated nationalism have suffered big losses: for example, Theodore Roosevelt in 1912; Robert La Follette in 1924; and George McGovern in 1972. Abraham Lincoln’s two most extraordinary speeches – the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural – told the hard truth that neither the Constitution nor its guiding principle, the Declaration of Independence, is “self-inducing.” The principles pronounced in the Declaration and the Preamble of the Constitution, he warned, could only be moved toward with constant striving and struggle.

Tulis and Mellow do acknowledge that Goldwater “made a serious mistake” in not supporting Civil Rights and failing to denounce the segregationists who supported his assault on Eisenhower’s “Modern Republicanism” (141). I would add that Goldwater’s messianic assault on the Liberal State’s principles and policies at home and abroad paved the way for a conservative – perhaps ascriptive – nationalism. Beginning with Nixon – and more decisively with Reagan (who formed an alliance with the Christian Right) – a Republican base (a “silent majority”) is summoned on the premise that liberalism had so defiled “traditional values” in domestic and international affairs that the national state had to be reconstituted, not rolled back, to serve them. In the promotion of policies against abortion and same sex marriage; in support of law and order; and in defense of national security – extended with a vengeance to the protection of the homeland – the critiques of the Liberal State have conceived consolidation as a two-edged sword. Consequently, amid the constitutional assault on the New Deal a conservative statism has emerged, the breeding ground of authoritarian nationalism. Donald Trump is not an aberration; rather, like Andrew Johnson, he is an opportunistic demagogue who has tapped into developments fifty years in the making to advance an illiberal understanding of what makes America great.

About the reviewer

Sidney M. Milkis – University of Virginia

Sidney M. Milkis – University of Virginia

Sidney M. Milkis is the White Burkett Miller Professor and the Cavaliers’ Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of Politics and a Faculty Associate at the Miller Center. His books include Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party, and the Transformation of American Democracy (2009); and Rivalry and Reform: Presidents, Social Movements and the Transformation of American Politics (2018).

Steven Bilakovics: “The purported losers of the transformational contests should not be considered mere footnotes to history”

History, we all know, is written by the winners. What we typically fail to recognize is the extent to which history has been revised by the losers. This is the central insight of Legacies of Losing in American Politics, the fascinating new contribution to American political thought, American political development, and constitutional theory by Jeffrey K. Tulis and Nicole Mellow.

Tulis and Mellow advance three central claims. Each leads us to see beyond simple narratives of the American story and recognize the paradoxical complexities that make up the American regime.

First, they detail the agency and ultimate efficacy of supposedly silenced and forgotten minorities. During the most radically transformative moments in American history, the subordinated voices of the “losing” sides were far from vanquished. Rather, they played an often decisive role in steering or stalling the course of events. Battles were lost, but the losing tactics proved to be part of a broader strategy to, if not win the war, then at least to keep it going.

At the time of the Founding, the Anti-Federalists’ conservative opposition to the Constitution was so pronounced and persuasive that the frankly radical pro-Constitution Federalists were obliged to promote ratification under false pretenses. So convoluted were the Federalists’ logic of institutionally mediated self-government, and so much more self-evident were Anti-Federalist associations of popular rule with localism, populism, and small republicanism, that the Federalists were compelled to defend the Constitution in terms of revision rather than re-formation, in terms of a moderate federalism. In their “disingenuous” arguments, the Federalists became what they most feared: demagogues. This winning strategy of rhetorical appeasement proved to be partially self-defeating, however, as the Anti-Federalists were furnished with an interpretive Trojan Horse through which they could appropriate the spirit and meaning of the document.

Every teacher of American politics has confronted this irony. Once it is established that partisanship existed all the way back in the time of the “Founding Fathers,” students find it difficult to comprehend that the advocates of the Constitution were the radicals, progressives, and partisans of centralization. Even as the Federalists won ratification for their modernizing political sociology, the Anti-Federalist opposition successfully recast the iconography of the Constitution in conservative, decentralizing, and states’-rights terms.

We might wonder, on the authors’ description of the Federalists’ project of national consolidation, whether we could ever overshoot the aims of the framers toward displacing the authority of the states entirely. Tulis and Mellow view the Federalists as “provoked” to offer a “mollifying” rhetoric of moderate federalism, between confederation and unfettered centralization. Yet it is clear that such federalism was never part of the plan. While it may be prudent for the national government to allow the states some semblance of self-administration, they were to retain no essential sovereignty. But does this overstate the case, particularly for James Madison, who, over the course of his career, adhered to moderate federalism?

Tulis and Mellow proceed to demonstrate how the Anti-Federalists’ politics of appropriation served as a vehicle for conservative reactions against Reconstruction and the New Deal. While President Andrew Johnson lost the battle over Reconstruction, he was able to marshal what we can call the “conservative constitution” to pursue a politics of obstruction in the name of a lost cause. By persuasively arguing that Radical Republicans in Congress were overstepping their constitutional bounds and forcing liberal freedom and equality down the throats of the legitimately self-governing Southern states, Johnson used the Constitution to give moral and material aid and comfort to a century plus of racist and sexist hierarchy.

Here we might notice an additional reversal the authors don’t articulate, in which the interpretive successes of the Anti-Federalists were themselves co-opted by the regimes’ illiberal elements, against the liberal and republican aims of the Anti-Federalists. The doctrine of states’ rights has been poisoned through association with the nation’s original sins of slavery and racism. Indeed, the authors themselves frequently elide conservatism, populism, localism, illiberalism, and hierarchy.

As the hierarchies Andrew Johnson sought to preserve were subject to renewed assault under the auspices of the Great Society in the mid-1960s, Barry Goldwater conducted a monumentally unsuccessful presidential campaign. His campaign was geared not toward conservative obstruction but toward propagating a new conservative movement. Goldwater, like Johnson, had no shot at conventional success. But election into the administrative nanny-state status quo wasn’t really the aim of this ruggedly independent neo-Cincinnatus. Rather he aimed to disrupt conventionality, to alter frames of reference and philosophical presuppositions, and so to incubate opportunities for change. More a preacher seeking converts than a politician pandering for electoral success, Goldwater the anti-triangulator thus practiced a politics of principled integrity that paved the way for the Reagan Revolution and the libertarian conservative framework within which we still operate.

Second, Tulis and Mellow complicate conventional narratives of American political development that depict these three eras as break points or born-again moments in the lifecycle of the American regime. While the Founding is such a rebirth, the subsequent events are better understood as important reiterations of the founding debates. Once we recognize the complex partisanship that was written into the genetic code of the nation at the time of the Founding, we properly understand American political development as the unfolding of an inner dynamic comprised of distinct and antagonistic but intertwined or “braided” traditions. There was one genuinely “trans-formative” or founding moment; Reconstruction and the New Deal are better cast as transitional moments of renovation. There is a general trajectory to American political development, but it is not one of unalloyed liberal progress. Rather, countercultural backlashes perennially take shape and exert sociopolitical influence in the constitutional spaces carved out by the opponents of the Constitution. The constitutional deck was stacked against the losers, but they were nonetheless able to tap into certain symbolic and interpretive undercurrents surrounding the document.

Third, Tulis and Mellow complicate our vision of the Constitution itself. In their constitutional theory the document is not merely the written rules of the game, which must either be followed to the letter or altered to accommodate changing circumstances. Rather, the text is the architectural blueprint for a way of life. It is less legal apparatus than political vision, with “political” understood in the classical sense as the foundational and just ordering of things. The Constitution is the word that has created the changing conditions that we mistakenly believe renders the document obsolete. The New Deal was latent in the Necessary and Proper Clause, presaged by the “animating political logic of national development” of the Constitution. Less constraining than prescriptive and catalytic, the Constitution is, in Aristotelean terms, the formal cause of the polity.

We can, I suggest, identify an additional layer to the complex composition of the American regime Tulis and Mellow analyze. Below the way of life framed by the Constitution we find the democratic way of life. In the culture of democratic equality, the powerless possess a certain moral standing. While we may “revere winning above all else,” as Tulis and Mellow write, we also resent the winners. The exercise of power – any semblance of superiority, command, or privilege – offends our egalitarian sensibilities and paradoxically undermines claims to authority. To be in a position of power is to be unprincipled by purely democratic standards. We may love the power, but we hate the power holder. There is an innate democratic hostility to the elected. Democratic moral authority thus gravitates toward not the dominant winners but to the marginalized losers, to those who (often perversely) claim the innocence and purity of powerlessness – to the Southern lost cause and the Goldwater anti-political outsider. In this way too loss may actually constitute success.

About the reviewer

Steven Bilakovics – UCLA

Steven Bilakovics – UCLA

Steven Bilakovics is the Director of the Commercial Republic Project at the Center for the Liberal Arts and Free Institution in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Los Angeles. He teaches courses on democracy, capitalism, American political thought, and the history of political thought. Bilakovics is the author of Democracy without Politics (Harvard University Press, 2012). His current work include a critique of the constitution, broadly understood, of market society, and an interpretation of the rhetoric (particularly after 9/11) wherein crisis is represented as an opportunity for civic and democratic renewal.

Authors’ response: Jeffrey K. Tulis (University of Texas at Austin) and Nicole Mellow (Williams College): “Our critics’ thoughtful observations provide a richer understanding of our argument, its possibilities and its limitations.”

We are grateful for these thoughtful critiques of Legacies of Losing in American Politics. In the book, we ponder the complexities of assessing success and failure over the long run. Sometimes policies and actions are not as successful in time as they appeared to be at first, and in other cases, initial failures turn out to be more successful than anticipated. Over time, readers of our book will determine whether the arguments of the book are lasting and whether we have successfully responded to the challenges posed here. Fellow students of American politics and, we hope, their students will determine the legacy of Legacies. What we can say now, with certainty, is that we have learned and benefitted from the remarks of our colleagues and that whatever the ultimate merits of our position, civic discourse about the issues that concern us can be better today because of the probing engagement of our fine critics.

* * *

Richard Ellis: Anti-statism as the default tradition

Richard Ellis offers two related criticisms — that we don’t understand that cultural anti-statism has always been the default feature of American politics and that we mischaracterize Louis Hartz’s understanding of the liberal tradition.

Ellis’s most elaborate and probing criticism is that our three cases do not illustrate, as we claim, a neglected Anti-Federalist source of challenges to the constitutional order as much as they evidence the continued importance of a more fundamental anti-statist political culture. This is a serious dispute about what is more foundational for, and constitutive of, American politics: the Constitution or an antecedent political culture. If the Constitution is more important, it will over time constitute or reconstitute the political culture. If political culture is truly foundational, that would mean that the “capital C” Constitution does not actually constitute, but is itself the product of an anti-statist political culture. In our view, because Ellis fails to understand what it means for a Constitution to constitute, he sees our anti-moments as nothing more than evidence of what he calls the default status of anti-statism. He sees the success of the Anti-Federal effort that we describe in the book as illustrating his thesis, but rather than the challenge that it purports to be, Ellis’s view actually serves as further confirmatory evidence for one of our main arguments.

In our telling, both the proponents and opponents of the Constitution at the Founding understood that what was at stake in ratification was the long-term trajectory and shape of American politics. Both Federalists and Anti-Federalists understood the enormous constitutive significance of the Constitution. They agreed that replacing the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution would set in motion what we call a “political logic” that would transform an anti-statist and pro-states’ rights polity into a continent-wide regime of enormous power and scope. This would have implications for the economy, culture, and even the psychologies and dispositions of individual citizens, as well as for state-building. We stress in Legacies that an account of the political logic is different from a description of the normative dispute over the merits of this projected trajectory. What most regard as the debate between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists is this more familiar dispute over the benefits of the Constitution and the merits of a powerful national state. What is unrecognized is that the Federalists and Anti-Federalists agreed about the developmental trajectory that the Constitution would induce.

Photo by Anthony Garand on Unsplash

In Legacies, we argue that Reconstruction and the New Deal should be understood as articulations of this fundamental political logic of the Constitution. Our reading of political history is consonant with the best new work by historians of America on the founding era, such as Max Edling’s A Revolution in Favor of Government. In our account of how the Anti-Federalists, over the long run, succeeded in re-interpreting the Constitution as a project contrary to its fundamental political logic, we offer an explanation for what so many have found puzzling: despite substantial growth of the American state and the expansion of rights, an oppositional, often conservative, politics has periodically resurged and seems surprisingly resilient.

If one believes, as Ellis does, that there is nothing surprising about at least the anti-statist resilience, that anti-statism is the default constitutive regime posture, then one would need to explain how it is possible that the American state grew to be as massive and powerful as it is and how, even in conservative Administrations, its trajectory has not been reversed. Ellis himself suggests that we are right that the US has had one regime, not three, and we wonder if he fully grasps the significance of that concession.

Ellis offers the provocative idea that the losers at each of America’s constitutional moments were in a win/win situation. They won whether or not they lost initially because in either case an anti-statist objective was advanced. This misses, though, the distinction between winning office and winning one’s policy vision, a point we stress in the chapters on Andrew Johnson and Barry Goldwater. For Andrew Johnson to have succeeded initially, he would have needed to embrace some version of Reconstruction, not Restoration. For Goldwater to have won or at least done well electorally in 1964, he would have had to offer a version of “New Deal Lite.” In other words, if Johnson and Goldwater had won in the conventional ways, they would have had to modify or abandon their policy goals. In these instances, they would have actually lost by winning in the traditional sense. Ellis’s point about win/win is most true about the Anti-Federalist, who did nearly win the ratification battle, and it would have been much better from their perspective if they had. For reasons we detail in the book, the complicated agency of the Founding is very different from the subsequent two cases.

Finally, we turn to Ellis’s second criticism regarding our interpretation of Louis Hartz. In the book, against the conventional wisdom of the twentieth century that depicts American political history as the unfolding of a comprehensive and hegemonic liberal tradition, we elaborate and refine a multiple traditions thesis that sees liberal and anti-liberal strands braided throughout American political development. Ellis argues, in effect, that if one understands Hartz correctly, there is only liberal hegemony because liberalism, as Hartz and Ellis understand it, already includes an anti-statist component. It is entirely reasonable to assert that liberalism has an anti-statist aspect. But in our view, Ellis appears to couple anti-statism with anti-liberal attributes such as ascriptive hierarchies that impede equality. More importantly, our interest was in revising the liberal traditions thesis, often referenced to Hartz but also to Tocqueville and others, that has actually set the agenda for thinking about American politics for decades. We are not the first to do this. Rogers Smith’s work was pathbreaking on this front, and we begin from his understanding of the liberal tradition. Ellis offers an interesting argument with Smith and others on how best to interpret Louis Hartz, but we don’t need to wade into that debate here. We happily concede that Ellis may have a better reading of Hartz himself than we provide in the book, but we are more interested in the liberal tradition as it has been understood by others and as it has functioned in American political discourse than in the details of Hartz’s understanding. In our revision of the liberal tradition debate, we supplement liberal and anti-liberal ideas with an account of America’s constitutional and anti-constitutional traditions. Ellis himself seems to realize our aim when he conjoins Hartz’s more sophisticated rendition with Samuel Huntington’s simpler idea of an American creed.

Sidney Milkis: The New Deal as a constitutional revolution

As with Richard Ellis’s remarks, we are humbled and grateful for the generous comments of Sidney Milkis, from whose scholarship we have learned so much, especially about parties vis-a-vis the modern administrative state and the relationships of presidents to social movements. That Milkis, like Ellis, seems to misunderstand our point about a constitutionally induced direction to American political development means that we were not clear enough about what we call the political logic. We’ve tried to rectify this in responding to Ellis’s remarks, but here we might add that while Milkis is right to say that the Constitution was “hotly contested from the start,” our point is that this contest over the merits of the proposed Constitution arose out of an understanding that was not contested — the meaning of basic features of the Constitution, or what we refer to as its political logic. On this the Anti-Federalists and Federalists were in complete agreement. The subsequent “fundamental struggle over its meaning,” as Milkis calls it, came about only because the Anti-Federalists and their heirs were so successful at re-deploying defensive, mollifying language in The Federalist about the political logic to promote their own, contrary interpretive project.

As we explain in the book, the Anti-Federalists’ initial attack on the proposed Constitution prompted the Federalists to develop a response that moved from reassurance that the proposed change was not fundamental to a sophisticated argument that it was. This rhetorical structure is reflected in the Constitution itself which contains fundamental nationalist attributes along with ancillary states’ rights language. After ratification, Anti-Federalist heirs successfully appropriated The Federalist’s early assuaging rhetoric as well as the ancillary features of the Constitution to achieve through interpretation what they lost at ratification: namely, to preserve the spirit of the Articles of Confederation and to continue to contest the nationalist project of the Constitution. The Anti-Federalist success with this multi-step process of rhetorical appropriation was so profound that most observers, including Milkis, take at face value that the well-known fight over the meaning of the Constitution was inevitable, forgetting or not seeing that both contestants in the ratification battle agreed on the meaning of the Constitution’s political logic. Like Ellis, Milkis’s interpretation evidences the power of the Anti-Federalists’s appropriation on American political consciousness as a whole, including the thinking of scholars. His disposition and reaction is evidence for our key thesis, not a compelling argument against it.

Steven Bilakovics: Americans often resent winners

Sometimes a critic renders one’s argument more cogently than the authors’ original formulation. Steve Bilakovics does that here. He reorganizes our argument around three themes: 1) complications revealed by treating losing as a form of agency; 2) complications of conventional narratives of constitutional development; and 3) complications of the meaning of the Constitution itself. In his insightful depiction of many of our main arguments, Bilakovics raises four useful and probing provocations.

First, Bilakovics notes the ironies that attend losing as a form of agency. However, in restating our observation that the Federalists, in changing and developing their arguments, provided the Anti-Federalists with the resources to later advance an anti-statist project, he suggests that the Federalists’ strategy necessitated that they “became what they most feared: demagogues.” This interpretation goes much further than we do in describing the irony that the rhetorical mechanisms Federalists used to win approval of the Constitution provided resources for those defeated by ratification to successfully use later. In our telling, it is the Anti-Federalists’ demagoguery that provoked the response of the Federalists. On every significant topic of concern—from states’ rights to executive power to the judiciary—The Federalist is iterative, misleading initially but subsequently reversing to defend that which had earlier been downplayed. Nonetheless, The Federalist’s rhetoric is tempered and reasoned throughout. In contrast, Anti-Federalists were more likely to depict the future with a sense of dread in order to provoke fear regarding ratification and the consequences of the future polity envisioned by the Constitution. The Federalist responded with a rhetoric that was mollifying, not incendiary. It is the early parts of this careful and tempered unfolding of the nationalist position that is later appropriated for states’ rights purposes. “Disingenuous” may aptly depict this rhetoric, but not demagoguery, which is often understood as an excessive appeal to passion.

Second, Bilakovics suggests that we overstate James Madison’s nationalism. Madison’s careful rhetoric might be better understood as a moderate version of federalism which he held consistently throughout his career. Our view is that we may have understated Madison’s nationalism during the time of constitutional ratification. After all, he advanced nationalist proposals, such as the Congressional veto of state legislation, that were rejected by the convention in Philadelphia; his famous Notes on the Philadelphia convention are usually thought to be even more nationalist than the papers he authored in The Federalist; and those convention notes themselves may understate Madison’s nationalism, as Mary Bilder has shown in her recent book, Madison’s Hand. Bilder examines Madison’s revisions of the Notes under the influence of Jefferson after the Constitution was ratified. However, for us, the trajectory of Madison’s thought over the course of his career is of less significance than the coherence of The Federalist itself. We try to show how the authority of that iconic text is later usefully appropriated by heirs of the Anti-Federalists because its nationalist argument is unfolded over the course of the ratification debates. The fact of Madison’s authorship is used by Anti-Federalist heirs to fortify their claim about the legitimacy of their interpretive project.

Bilakovics’ third provocation raises an important and justified criticism of our presentation. In the book, although we touch on this point, we were not clear enough in reminding readers that the nationalist/states’ rights divide during the founding period did not align squarely with the divide opposing or supporting slavery. The original Anti-Federalists did not necessarily conjoin states’ rights and slavery, or states’ rights and all versions of conservatism and ascriptive hierarchy. As we show in the chapters on Johnson and Goldwater, the heirs of the Anti-Federalists appropriated the iterated Federalist arguments, including those that seemed to elevate states’ rights, in ways that would have been disapproved of by many original Anti-Federalists. Moreover, while we do discuss how strands of the Federalist/nationalist tradition also were sources of later anti-constitutional practices, Bilakovics is correct to suggest that we frequently elide conservatism, populism, localism, illiberalism, and hierarchy. We hope that our framework of a four-stranded braided tradition will give thoughtful readers, like Bilakovics, the resources to better articulate and refine the sources and relationships of these multiple isms.

Finally, Bilakovics suggests an additional layer to the complex composition of American political culture. In addition to revering winning, Americans, Bilakovics notes, often resent winners. The democratic passion for equality, he reminds us, generates envy, and any claims to superiority, including those that are the product of democratic elections, offends the basic egalitarian sensibility. “Democratic moral authority thus gravitates . . . to the marginalized losers . . . and the powerless. . . In this way too loss may actually constitute success.” Bilakovics’ final observation is an extension of our argument that we did not see until he pointed it out. We certainly agree with it and are grateful that in this important way he has understood, and deepened, our argument.

* * *

We noticed a strand that runs through the responses of all three of our critics. Elements of each evidence, rather than challenge, the legacies of losing in American politics. Ellis’s focus on anti-statism as fundamental, Milkis’s understanding of the administrative state as a new product of the New Deal, and Bilakovics’ Anti-Federalist reading of Madison’s federalism, for examples, all reveal the continuing, commonly unnoticed, power of the losing tradition in American constitutional politics.

We wish to end as we began, with an expression of deep gratitude to all three of our critics for the thoughtfulness of their remarks, the clarifications they compelled us to make, and the insights about American politics they shared. If readers of this forum are sufficiently intrigued to read Legacies of Losing in American Politics, this exchange will hopefully continue a conversation we tried to begin. We can’t thank our critics enough for their thoughtful observations which provide a richer understanding of our argument, its possibilities and its limitations.

About the authors

Jeffrey K. Tulis – University of Texas at Austin

Jeffrey K. Tulis is a Professor in the Department of Government in the University of Texas at Austin. His interests bridge the fields of political theory and American politics. His publications include The Constitutional Presidency (Johns Hopkins, 2009), The Limits of Constitutional Democracy (Princeton, 2010), and The Rhetorical Presidency, (Princeton, 1987, Princeton Classics edition, 2017).

Nicole Mellow – Williams College

Nicole Mellow – Williams College

Nicole Mellow is a Professor of Political Science at Williams College. Her research interests are in the field of American political development. She is the author of State of Disunion: The Regional Sources of Modern American Partisanship (Johns Hopkins, 2008) as well as articles on political parties, the presidency, and American eugenics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This review gives the views of the reviewers and authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2WAYppG

1 Comments