In the United States, Congressional boundaries are drawn at the state level, either by the courts, independent commissions, or by the state legislatures themselves. While judge-drawn district lines have been shown to lead to more competitive elections, in new research, Jordan Carr Peterson finds that when they are drawn by Democratic judges, they often favor that party’s interests by making Republican-held districts more competitive.

In the United States, Congressional boundaries are drawn at the state level, either by the courts, independent commissions, or by the state legislatures themselves. While judge-drawn district lines have been shown to lead to more competitive elections, in new research, Jordan Carr Peterson finds that when they are drawn by Democratic judges, they often favor that party’s interests by making Republican-held districts more competitive.

Despite the 2020 presidential race taking up much of America’s political imagination, there are many in academia and the popular media who have also been paying close attention to how the states redistrict Congressional boundaries. This attention came to the fore this week with huge interest devoted to the outcome of the recent litigation Rucho v. Common Cause, where the US Supreme Court held that challenges to redistricting maps based on allegations of partisan gerrymandering are nonjusticiable political questions – in other words, they are disputes the federal courts are unable to remedy.

The boundaries of legislative districts profoundly impact the relationship between representatives and constituents, and by extension, between the government and the governed. The range of preferences motivating those who draw district lines can therefore have massive consequences for the character and quality of democratic governance.

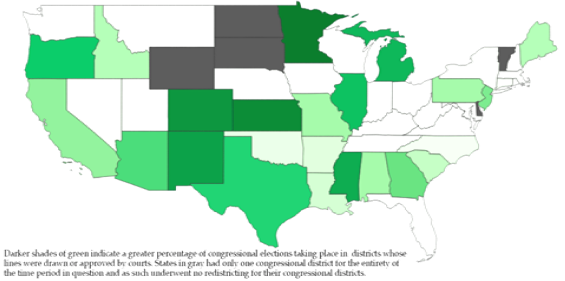

Due to the federal framework of American government and the prevailing use of litigation to resolve disputes in American politics, the determination of legislative district boundaries in the United States occurs by a variety of methods. While most states assign the responsibility of drawing legislative constituencies to their state legislature or a limited-jurisdiction commission, legal challenges to districting plans often result in district maps either being drawn or approved by courts. Figure 1 shows the variation in redistricting method among states, where darker shades of green indicate states in which a greater percentage of congressional elections from 1982-2012 took place in districts whose lines were determined by a court or judge.

Figure 1 – Judicial redistricting in the American States, 1982-2012

Scholars have argued or shown that redistricting results in more competitive elections when judges draw district lines, typically implying this result occurs because courts are more politically neutral than legislatures when it comes to partisan districting considerations, as legislators have clear partisan incentives when drawing lines. In new research I argue and find that while districts are indeed most competitive when judges draw the lines, judges also systematically favor congressional candidates from their own preferred party.

How can it be that judges simultaneously make elections more competitive while advancing the electoral interests of those in their own party? I argue this is possible because judges deciding redistricting cases employ a strategy of partisan calculation in which they enhance overall electoral competitiveness in a state, but that the districts made more competitive in judicial redistricting are those held by legislative incumbents from the opposite party as the judge. For example, if a judge favoring the Republican Party is responsible for determining a state’s redistricting, the state’s congressional elections might become more competitive on average, but the judicial plan would – according to my theory – favor Republican interests by making districts held by Democratic congressional incumbents more competitive.

“US Department of Justice gives nod to North Charleston redistricting” by North Charleston is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

To test whether the effects of judicial redistricting on electoral competition were targeted toward districts controlled by the party opposite the judge, I specified a series of statistical models to examine the association between redistricting method (either legislature-drawn, commission-drawn, or court-drawn) and a set of electoral outcomes. I find that while judicial redistricting results in more competitive elections, Democratic congressional candidates also benefit electorally in districts drawn or approved by Democratic judges.

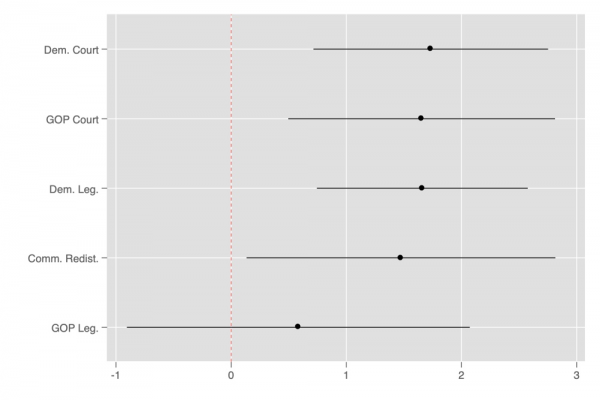

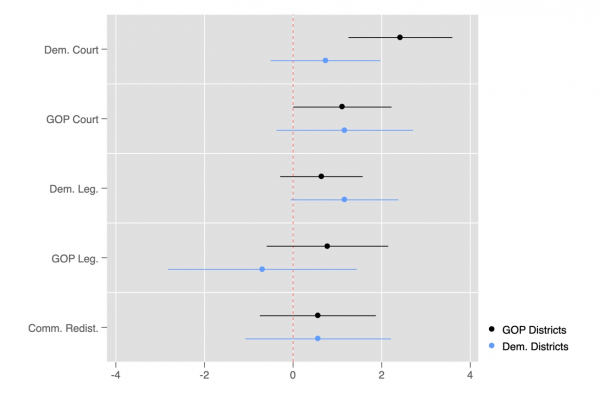

These findings are reflected in Figure 2, which plots the estimated effects of different redistricting institutions (Democratic courts, Republican courts, Democratic state legislatures, Republican state legislatures, and redistricting commissions) on Democratic vote share compared to state legislatures under split partisan control. Relative to divided state legislatures, Democratic candidates saw increased vote share in districts whose lines were drawn by any institution other than Republican-controlled state legislatures. Figure 3, however, demonstrates that the positive effects of Democratic judicial redistricting on Democratic congressional vote share are limited to districts controlled by the Republican Party prior to the election. This implies support for my theory of judicial partisan calculation among Democratic judges, whether at the federal or state level.

Figure 2

Figure 3

In sum, while judges do increase the level of competition in congressional elections, they do not do so in an equal opportunity manner across districts. Instead, at least some judges engage in sophisticated partisan calculation by evidently targeting districts held by the opposing political party, and attempting to jeopardize the electoral safety of congressional candidates from that party. Future work should consider why these effects are limited to Democratic judges, who may demonstrate philosophical commitments to a more activist judiciary; and might explore in greater depth how differences across state and federal legal institutions (e.g., whether judges were elected or appointed, whether elected judges ran in partisan or nonpartisan elections, etc.) condition the effects of judicial redistricting on election administration.

- This article is based on the paper,’ The Mask of Neutrality: Judicial Partisan Calculation and Legislative Redistricting’, forthcoming Law & Policy.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ZYkZqy

About the author

Jordan Carr Peterson – Texas Christian University

Jordan Carr Peterson – Texas Christian University

Jordan Carr Peterson is an assistant professor of political science at Texas Christian University. He studies American legal and political institutions and their relative capacity as sites for policy formulation, development, and implementation.

1 Comments