In Healthy or Sick? Coevolution of Health Care and Public Health in a Comparative Perspective, Philipp Trein examines the coevolution of policies to prevent diseases (public health) and policies aimed at curing illnesses (healthcare) through a comparative historical analysis of Australia, Germany, Switzerland, the UK and the US. This is a much-needed contribution to the field, finds Michael Warren, providing a valuable analytical framework that may help shed light on how these large sectors can meet twenty-first-century challenges.

Healthy or Sick? Coevolution of Health Care and Public Health in a Comparative Perspective. Philipp Trein. Cambridge University Press. 2019.

Healthcare is a large sector; within it, policymakers specialise in regulation, child health, medicines, hospital-building, workforce issues and many more areas that, like the TARDIS in Doctor Who, look small on the outside but are vast and complex on the inside. A challenge, not unique to healthcare, is how to get these areas to not simply co-exist but to work in tandem. Healthcare commentators talk about transitioning from ‘fragmentation’ to being ‘joined-up’ and ‘integrated’. Moving from aspirational buzzwords to reality is difficult, but Healthy or Sick?, the new book from Philipp Trein that analyses how the coevolution of policies to prevent diseases (public health) are related to policies aiming to cure illnesses (healthcare), may help shed light on how to coevolve two large policy sectors and ensure that the systems in which they exist are ready for twenty-first-century challenges.

The central thesis of Healthy or Sick? is that integrated or cohesive healthcare and public health policymaking in Western countries stem from two factors. Firstly, a combination of a strong national government that possesses a wide range of control over subnational levels of government. Secondly, whether professional organisations (Trein focuses primarily on doctors) perceive preventative and non-medical health policy as important and actively campaign for it. Trein uses five case studies: Australia, Germany, Switzerland, the UK and the US. These case studies are analysed over a huge time period of 1880 to 2010. Whilst this wide scope of 130 years of policy history across five countries is admirable, it means that the study is a high-level approach and sometimes does not drill down into the nuts and bolts of policy workings to fully understand the reasoning behind policy directions amongst the countries.

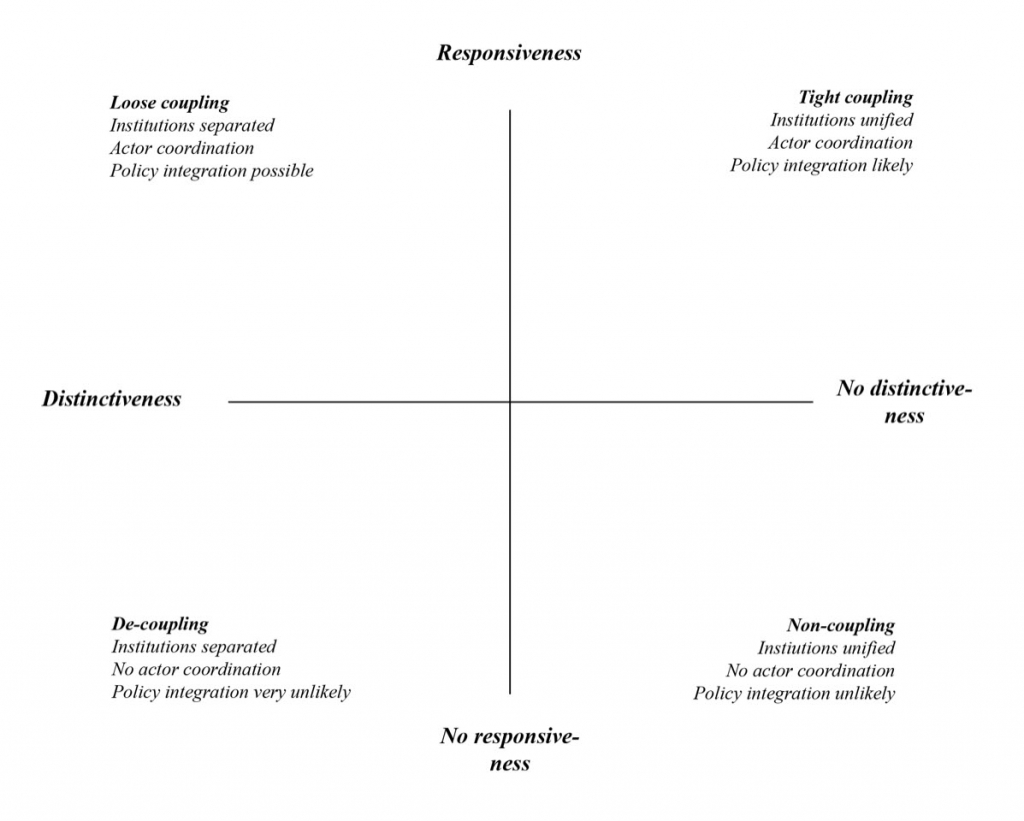

Rather than using the terms cohesion or integration, Trein talks about the ‘coupling’ of policy sectors. Where two policy sectors are tightly coupled, they are not distinctive— that is, they share common structures and are institutionally unified —and have high responsiveness— professionals and administrators from both sectors formally coordinate activities. Here, Trein gives an example of successful coordination as medical associations’ support for tobacco control and involvement in its implementation.

Image Credit: Figure 2.1. Ideal-typical coupling of policy sectors. From Healthy or Sick?, page 31. Philipp Trein. Image provided courtesy of Philipp Trein and Cambridge University Press. Reproduced with permission of The Licensor through PLSclear.

Image Credit: Figure 2.1. Ideal-typical coupling of policy sectors. From Healthy or Sick?, page 31. Philipp Trein. Image provided courtesy of Philipp Trein and Cambridge University Press. Reproduced with permission of The Licensor through PLSclear.

Healthy or Sick? finds that Anglophonic countries (Australia, the UK and the US) coevolved from non-coupling and loose coupling to a tight coupling of healthcare and public health, whilst Germany and Switzerland have low responsiveness and have moved from decoupling to non-coupling. This means that the non-Anglophone case study countries do not have as well-coordinated public health programmes as the Anglophone ones which can impact their respective populations negatively. However, the varying impacts of the different levels of coupling are not explored in detail by Trein: the book is very much orientated around the causation of coupling rather than the effects.

Although differences abound between the five countries, Trein finds that there are two similarities between all of them. Firstly, there were reduced responsiveness and increasing conflicts between the medical profession and public health specialists from 1918 to 1945. In this period, the source of contention was the role of the state in health provision, which meant medical professionals successfully opposed the creation of national health services in all countries and secured individual healthcare policy’s dominance over public health. Secondly, post-1980 all countries were more institutionally unified and increasingly integrated in actual policies of healthcare and public health.

Of the two parts to Trein’s thesis, unified government and actively political professionals, the latter is narrower in scope. Although arguably, regarding healthcare professionals, a medical doctor often retains higher status in healthcare teams and in society, other healthcare professionals also hold status and can sway policymakers and the public, such as dentists and nurses. Trein shows that beyond the obvious reasons for being involved in public health (to care for the population), physicians often had other reasons. For example, physicians in the USA between 1880 and 1918 were eager to participate in public health activities as it offered ‘intellectual distinction’ due to being part of a social reform movement and also provided extra income to supplement their day jobs.

One omission from the book is the devolution of the UK’s healthcare systems to England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, which have been four politically autonomous systems since 1998. This has resulted in the creation of corresponding agencies – Public Health England (2013), Public Health Wales (2009), NHS Health Scotland (2003) and the Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland (2009). Devolution or decentralisation is not unique to the UK and can be found elsewhere: for example, in Italy and Spain. At the other end of the policy stakeholder chain, supranational bodies such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the European Union (EU) have a role too: arguably of increasing importance when one considers the greater potential for pandemics to spread. Trein briefly mentions that the ‘pressure’ of the EU Commission and Directives enabled public health laws and regulations to pass in Germany. The tension between decentralisation/devolution and supranational coordination is an area ripe for further research on the back of Healthy or Sick?.

Readers looking for a granular analysis and new information may be disappointed. This book takes its evidence primarily from secondary literature, peppered with some interviews with experts. However, looking at the book exclusively from the vantage point of granularity and new raw data is to ignore the uniqueness of the work. Few studies compare the development of multiple policy sectors and analyse how they mutually influence each other. Healthy or Sick? makes a much-needed contribution to that area, providing an analytical framework to understanding the coevolution of policy sectors and how this can potentially be transferred to other sectors beyond healthcare: for example, homeland security, domestic security and migration and refugee policy. With the glut of data now at our fingertips, there may be food for thought for policymakers in how to coordinate and combine technology policy with public health and healthcare sectors. This will be timely as public health issues, such as obesity and infectious diseases like Ebola, mean public health is back on the public agenda.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Feature image credit: sergio santos nursingschoolsnearme.com/ (CC BY 2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2JcYrfS

About the reviewer

Michael Warren – Professional Standards Authority

Michael Warren completed an MSc in Empires, Colonialism and Globalisation at the LSE in 2012, and graduated from the University of Sheffield (studying on exchange at the University of Waterloo, Ontario) with a BA in Modern History in 2011. He researched on an open data project for Deloitte and the Open Data Institute, and worked for the All-Party Parliamentary Health Group and as a Management Consultant in Health and Public Service at Accenture. He is a Policy Adviser at the Professional Standards Authority.

Find this book:

Find this book: