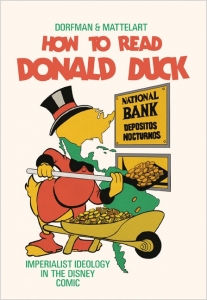

Originally published in 1971 in Chile to intense opposition from the right-wing media, in How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic, Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart offer a cultural critique of Donald Duck comic strips, showing them to be far from benign products of the US cultural industry. Recently reissued, the book is at once an incisive political intervention, a historical artifact of its time and place, a pioneering analysis of mass culture and a privileged starting point to reassess the political potential of cultural critique, writes Marcos Gonzalez Hernando.

How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic. Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart (trans. by David Kunzle). Pluto Press. 2019.

It is exceedingly rare that a book of cultural analysis, especially one from outside the ‘First World’, reaches the fame (or infamy) that How to Read Donald Duck did in its day. At a time when the humanities and social sciences are frequently accused of irrelevance and abstruseness, it is curiously inspiriting to read in the book’s preface the opposition it roused. Its first edition was the target of rabid opprobrium from the mainstream press; after Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup d’état, thousands of copies were thrown into the sea in Valparaíso bay; and its English translation endured decades of copyright disputes before it could be published in the US. As such, the book is as such an incisive political intervention, a historical artifact of its time and place, a pioneering analysis of mass culture and a privileged starting point to reassess the political potential of cultural critique. Hence, it is no exaggeration to say it is a gem in the history of the social sciences.

To properly understand the book’s significance, it is crucial to highlight the context in which it was written: in Chile, during the Cold War. Though the fact is seldom remembered, after the establishment of several international research institutes in the 1950s – e.g. the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC); Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) – and the concomitant emergence of university social science departments, Santiago became one of the most important centres of social research in Latin America, and perhaps anywhere outside Europe and North America.

Though many were initially supported by US agencies, as time went by these institutions began to produce ideas that overstepped what their patrons expected – for instance, dependency theory in economics and Marxist theory in sociology. These tendencies only accelerated after the revelations surrounding Project Camelot in 1965 – a counter-insurgency scheme sponsored by the US Department of Defense to study how to prevent ‘other Cubas’ from arising. Parallel to the political rise of left-wing parties, the Chilean social sciences and humanities took a sharp leftward turn, intriguing prominent outside intellectuals such as Régis Debray and Paulo Freire and attracting the attention of the world. A few years later, in 1970, an openly Marxist politician, Salvador Allende, became president for the first time in the Western hemisphere.

How to Read Donald Duck was first published in that context, in 1971, written by Ariel Dorfman (a literary scholar and playwright, also famous for Death and the Maiden) and Armand Mattelart (a Belgian sociologist, demographer and documentarist). Both advised and were supporters of Allende’s government. Their declared ultimate goal, as that of their political fellow travellers, was to provide tools for the economic and intellectual emancipation of the working class in Chile and elsewhere. They decided to focus on Donald Duck comic strips, seemingly one of the most benign products of the USA’s cultural industry that enjoyed tremendous commercial success in the country. By virtue of this very choice, they found steadfast opposition from the right-wing press, including scathing reviews from the CIA-backed El Mercurio, which claimed the authors’ antipathy towards Disney showed how dour and over-politicised the left had become. Presumably, there is something sacred about this kind of entertainment that should be kept apart from the affairs of adults.

Image Credit: (Ikbenhet CCO)

Image Credit: (Ikbenhet CCO)

The authors strongly objected. Their book is advisedly sacrilegious. These comics are produced by adults after all and, unavoidably, convey their views of what childhood is and should be. They offer a simpler world of wonder and play where seemingly timeless truths need not be tainted by the dreary aspects of grown-up life. As such, being a portrayal of (and the education given at) infancy, Disney’s cultural products can become part of the sediment of everyday life, the bedrock sustaining how the world is understood by the masses. It is in this sense that David Kunzle, in the Introduction to the English edition, suggests Disney Corporation’s ultimate aim is the privatisation of common culture – and not just for the copyright revenue.

Dorfman and Mattelart’s main premise is that the Disney worldview is neither anodyne nor innocent. To examine it, they drew inspiration from an array of theories – notably anti-colonialism, Marxism, psychoanalysis and Structuralism. Their erudition is apparent on every page, without ever making the book seem pedantic or tedious. Rather, it is mischievous and thrilling. They wanted their ‘roasting of the duck’ to be a joyous exercise, brimming with vivid metaphors to puncture a common sense that they thought entrenches inequalities in sexual, racial and colonial relationships.

Among the many original insights found in the book, one could mention their analysis of why the relationships between Disney characters are mostly avuncular (uncles, aunts, nephews, etc) rather than filial (parents, children). They link it to an atomistic view of human relations – where there are no births nor deaths, and no being is ultimately responsible for any other – and a phobia of sexuality, motherhood and women more generally. Dorfman and Mattelart also scrutinise the underlying architecture of most of Donald Duck’s plots: a race to discover hidden treasures in remote corners of the globe. These treasures are never actually built by the ‘savages’ the heroes dispossess, but rather are inherited and ignored by them – like the proverbial gold barely noticed by the inhabitants of ‘El Dorado’. In the end, all of it is transformed into coins for Uncle Scrooge to swim in. And any ‘bad guy’ we find in the journey from treasure to coin (some of whom actually shout ‘viva the revolution!’) is cast as both despotic and comically inept.

Though this book’s object of analysis might seem quaint and dated, its method and insights are still uncomfortably relevant, and the whole endeavour is carried out with wit and charm. It brings together in one stroke many of the preoccupations of progressive academics: economics, culture and empire; gender, race and class. The fact that it was burnt in the streets of Santiago as the military and the ‘Chicago Boys’ came to power should come as no surprise. One ought not to forget; there is an iron fist hidden inside the white velvet glove.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2YAcbWr

About the reviewer

Marcos Gonzalez Hernando – University of Cambridge

Marcos Gonzalez Hernando is Affiliated Researcher at the University of Cambridge, Senior Researcher at Think Tank for Action on Social Change (FEPS-TASC), and Managing Editor at Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory. He has experience teaching research methods and social theory at the University of Cambridge, City, University of London, and Universidad de Chile, and his main research interests lie in the sociology of knowledge, particularly in what concerns experts, political elites and intellectual and policy change. He has recently published a book with Palgrave on the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis on British think tanks. His current research examines the composition and attitudes towards inequality of the top ten per cent of income earners in Ireland, Spain, Sweden and the UK.

Find this book:

Find this book: