More than 1 in every 8 Americans has a disability, and yet the role of disability with other characteristics such as race, gender, and education in contributing to disadvantage is relatively understudied. In new research, which uses sample data from more than two million Americans, Michelle Maroto and David Pettinicchio find that the effects of disability on poverty are greater for disadvantaged groups, such as minorities and those with lower levels of education. However, when examining total income, they find that disability has the greatest negative impact on advantaged groups like white men, who in effect have the most to lose.

More than 1 in every 8 Americans has a disability, and yet the role of disability with other characteristics such as race, gender, and education in contributing to disadvantage is relatively understudied. In new research, which uses sample data from more than two million Americans, Michelle Maroto and David Pettinicchio find that the effects of disability on poverty are greater for disadvantaged groups, such as minorities and those with lower levels of education. However, when examining total income, they find that disability has the greatest negative impact on advantaged groups like white men, who in effect have the most to lose.

Disability has often been ignored by mainstream scholars who look at inequality and how it is structured, leaving a significant gap in our understanding about the ways in which disability intersects with other status characteristics to produce disadvantage. In new work, we examined how disability – itself a status characteristic determining everything from health to educational outcomes to employment and financial wellbeing – intersects with gender, race, and education to contribute to social marginalization.

As we and other scholars note, social categories like disability, race, and gender do not exist independently of each other. They overlap and intersect, compounding disadvantages and shaping identities. Indeed, women with disabilities represent a distinct category of bias, facing double jeopardy as they are twice penalized.

Feminist scholars have repeatedly shown that these overlapping oppressions structure inequality. We extended this framework to explore how the intersection of disability, gender, race, and education shape economic (in)security. This is important in a context of declining social safety nets, market deregulation, and reductions in union strength, all of which contribute to increasing economic insecurity across already marginalized groups. Additionally, by focusing on economic insecurity more broadly, we looked beyond labor market outcomes which is just one, albeit important, factor shaping economic wellbeing.

This is especially relevant for people with disabilities who often rely on income sources outside the labor market. And, given their low employment levels and low earnings within a context of declining lifelong careers and decreasing reliance on employer–employee savings plans, it’s all the more critical to consider the broader financial picture.

As measures of economic insecurity and in addition to employment earnings, we analyzed total pre-tax personal income, which includes government-related income from public assistance programs, savings income from an estate or trust, interest, dividends, royalties, rents received, and pensions, and “other” income sources, such as transfers from family members. We also considered poverty status based on the respondent’s standing in relation to the government-provided poverty threshold as established by the US Social Security Administration. In total, these provide a better picture of a person’s economic standing.

Photo by marianne bos on Unsplash

A hierarchy of disadvantage

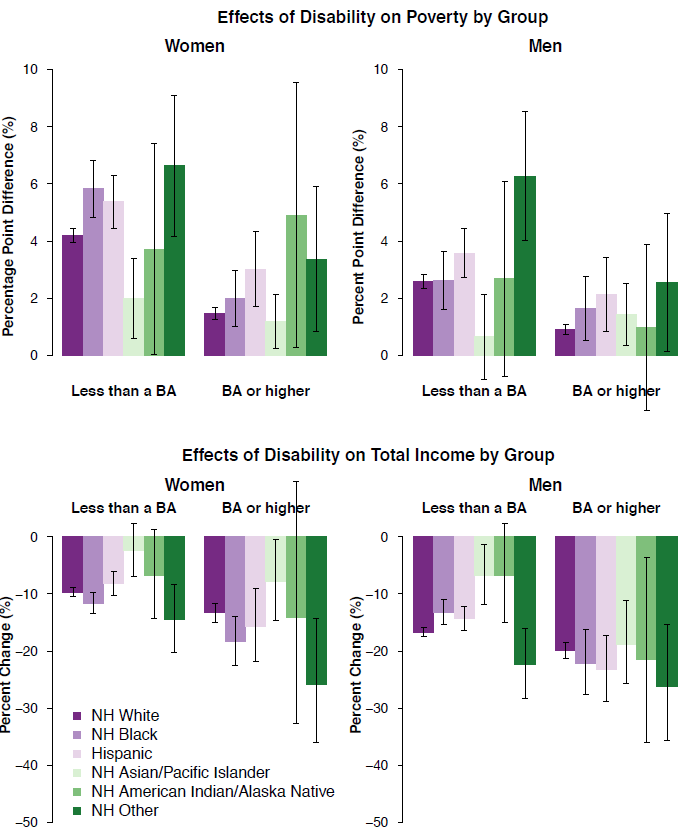

Using the American Community Survey and a sample of over two million Americans, we found a hierarchy of disadvantage that functioned in somewhat different ways across our two outcome measures. Figure 1 below highlights these different outcomes by showing the predicted percentage point difference in poverty (top panel) and the percent change in total income (lower panel) associated with disability among specific race, gender, and education groups. These results are based on models that include a variety of control variables, such as age, family structure, and employment.

Figure 1 – Effects of disability on poverty and total income by group

Note: Results from logit and linear regression models predicting poverty level and total income using 2015 ACS data (N = 2,490,616). Estimates refer to the effect of disability for members of the specified groups net of control variables. See paper for more details.

In the case of poverty status, hierarchies of disadvantage appeared in two ways. The relative effects of disability on poverty were larger for more disadvantaged groups, as shown in the figure, and the negative effects of disability compounded the effects of race, gender, and education on poverty. For instance, the effects of disability on poverty were approximately 40 percent larger for non-Hispanic white women than for non-Hispanic white men across education categories. Disability’s effects on poverty were also 55 percent larger for non-Hispanic black women than for non-Hispanic white men. As a result, predicted poverty rates were highest among racial minority women with lower levels of education.

White men have the most to lose in terms of incomes

However, while less-educated women with disabilities earned the least, we found that disability actually had a greater negative effect on total income for already advantaged groups, which is also highlighted by the figure. Consequently, non-Hispanic white men with higher levels of education experienced large disability-related income losses of 20-26 percent. Men had more to lose, in part because they rely more on employment income for their economic wellbeing than other income sources, such as government assistance. We also suspect that disability is more limiting for men because of how it conflicts with traditional norms of masculinity. Disability is often associated with notions of weakness, which undermines the ability of men with disabilities to inhabit masculine roles in the labor market.

Although disability led to the greatest income disparities within more advantaged groups, the combined effects of race, gender, education, and disability still resulted in a hierarchy of income, with less-educated women with disabilities earning the least. For instance, the predicted total annual income for black and Hispanic women with disabilities and less education was approximately $26,000 per year with other variables set at their means compared to $65,000 for non-Hispanic white men with higher education and with disabilities. Thus, even though members of more privileged groups had more to lose, the most disadvantaged groups still ended up at the bottom of the hierarchy.

The importance of education and support

There are other important take-aways from our findings. The first is that education plays a critical role in helping to lift disadvantaged groups out of poverty. Differences by education were much greater than those by race or gender. In addition to education increasing employment income, women and men with higher levels of education were also able to take advantage of savings to make up for limited income in other areas. Second, government support, savings, and other income sources helped mitigate the overall effects of lower earnings. This was especially important for people with disabilities who have much lower levels of labor market participation. If not for these additional supports, poverty rates among people with disabilities would be much higher.

Together, these findings emphasize, first, the importance of looking beyond employment and earnings when studying inequality, and, second, the need to do so from an intersectional point of view. Hierarchies of disadvantage were only apparent once we considered the multiple statuses that people inhabit. We show that when disability, gender, race/ethnicity, and class overlap, the meanings associated with membership in these groups compound to expand cumulative disadvantage.

- This article is based on the paper “Hierarchies of Categorical Disadvantage: Incorporating Disability into Intersectional Analyses of Economic Insecurity” in Gender & Society.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2TatoFa

About the authors

Michelle Maroto – University of Alberta

Michelle Maroto – University of Alberta

Michelle Maroto is associate professor of Sociology at the University of Alberta. Her teaching and research interests center on social stratification and extend to areas of gender and family, race and ethnicity, criminology, economic sociology, labor and credit markets, and disability studies. Her recent projects have focused on the causes and consequences of bankruptcy, wealth disparities in the United States and Canada, the effects of incarceration on wealth, and labor market outcomes for people with different types of disabilities. She is currently embarking on a new project that will examine dynamics of social class in Canada using survey and interview data.

David Pettinicchio – University of Toronto

David Pettinicchio – University of Toronto

David Pettinicchio is assistant professor of Sociology and affiliated faculty in the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. His new book, Politics of Empowerment: Disability Rights and the Cycle of American Policy Reform (Stanford University Press, 2019), investigates how and why seemingly entrenched policies like the ADA succumb to retrenchment efforts and the important role of both political elites and everyday citizens in mobilizing against these political threats.