Employment across the world has taken a huge hit because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Michelle Maroto and David Pettinicchio write that existing inequalities in earnings and employment mean that individuals with disabilities and other vulnerable groups have been especially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Employment across the world has taken a huge hit because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Michelle Maroto and David Pettinicchio write that existing inequalities in earnings and employment mean that individuals with disabilities and other vulnerable groups have been especially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the social distancing measures taken to combat its spread have created huge economic disruption in the US and elsewhere; by early May over 36 million Americans had filed for unemployment benefits, numbers not seen since the heyday of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Recent Current Population Survey (CPS) data for April 2020 underscore the employment effects of COVID-19. The Basic Monthly Current Population Survey (CPS) collects key demographic and employment data for a large sample of US households, making it an invaluable survey for understanding current trends across the country. These data show dramatic changes in employment between March 2020 and April 2020 for the general adult population, especially when compared to relatively small changes across these months in previous years.

A huge hit to employment

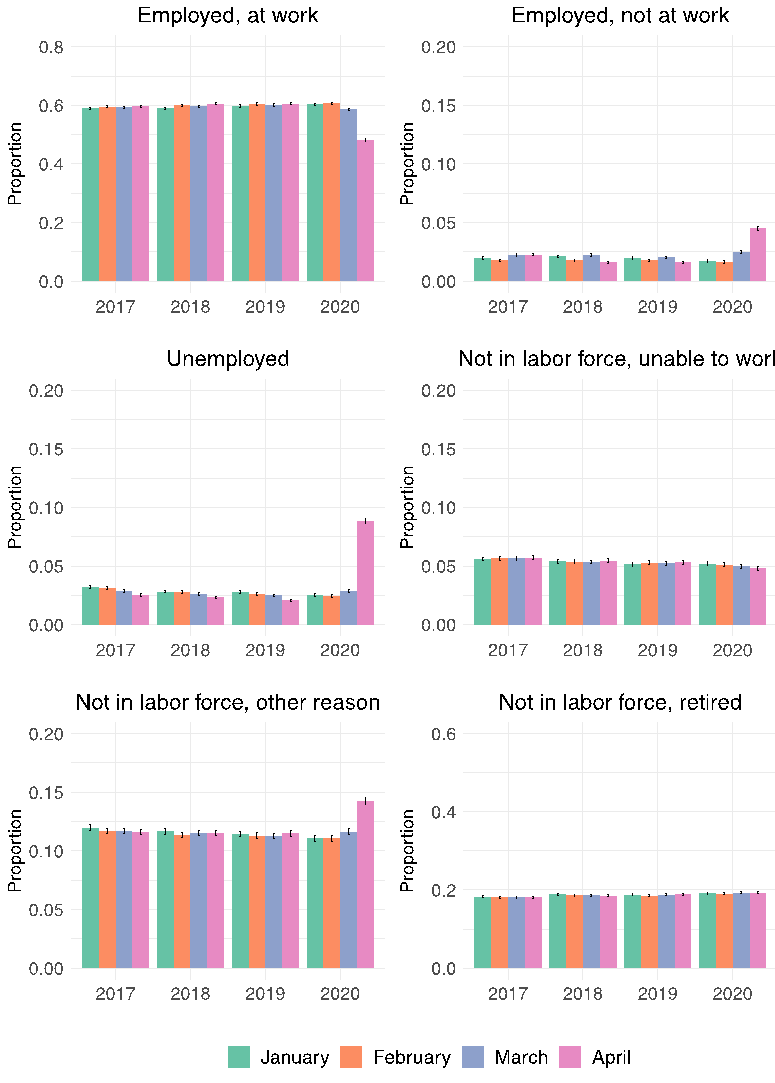

Figure 1 shows changes in employment status for workers in January, February, March, and April over the past four years. There is a steady drop in the percentage of people who were employed and at work in the week before. This percentage decreases from 60 percent in January and February 2020 to 59 percent in March 2020 to 48 percent in April 2020 – an 18 percent decrease between March and April. Most of these workers moved into unemployment, which rose from 3 percent in March to 9 percent of the entire adult population in April – a 210 percent increase. Increasing unemployment is further illustrated by the growing number of unemployment insurance applications.

Figure 1 – Employment Status for Adults Age 18+ and Older, January-April, 2017-2020

Source: Basic Monthly CPS for January-April 2017-2020, N = 1,498,578 adults (approximately 80,000 per month/year)

Notes: Error bars refer to 95 percent confidence intervals.

Individuals are usually counted as unemployed if they did not have jobs and were looking for work. However, a more detailed analysis shows that workers also moved into other categories of employment and labor force participation.

The percentage of workers who were employed but not at work increased from 3 percent to 5 percent between March and April – a rise of 80 percent. These are workers who acknowledged having a job but were temporarily absent from that job during the previous week.

Photo by Robert Ruggiero on Unsplash

Beyond employed and unemployed persons, workforce data also include people who are not in the labor force for various reasons including those who are not working and not looking for work. However, the CPS also includes a category for not in the labor force for “other reasons.” Between March 2020 and April 2020, the percentage of people in this category grew from 12 percent to 14 percent, an overall increase of 22 percent.

The unequal effects of COVID-19 on vulnerable groups

What is potentially masked by these broader numbers are the ways COVID-19 continue to disproportionately affect vulnerable groups — women, racial minorities, workers in low-paying jobs, people with less education, and people with disabilities.

For years, employment rates among people with disabilities declined while the number of discouraged workers with disabilities increased (these numbers are often masked by employment rates). Not surprisingly, disabled workers’ earnings have remained relatively stagnant over the last quarter century in part due to their clustering in low-paying, non-unionized sectors characterized by precarious work, uneven shift hours or subpar wages. Thus, like members of other vulnerable groups, people with disabilities were already structurally disadvantaged before the start of the pandemic.

Anecdotal accounts suggest that people with disabilities are more susceptible to the virus and, are significantly impacted by social distancing measures, as well as so-called “rationed responses” to the pandemic. People with different types of disabilities may be denied access to health care and other aids including masks and respirators particularly when these are in short supply. Many can no longer rely on care workers as they can’t or won’t enter individuals’ homes. This is especially detrimental to individuals who rely on care workers to lead lives outside of restrictive institutions and to participate in the labor market. This all the more significant given that nursing homes and the like have become COVID-19 hotspots.

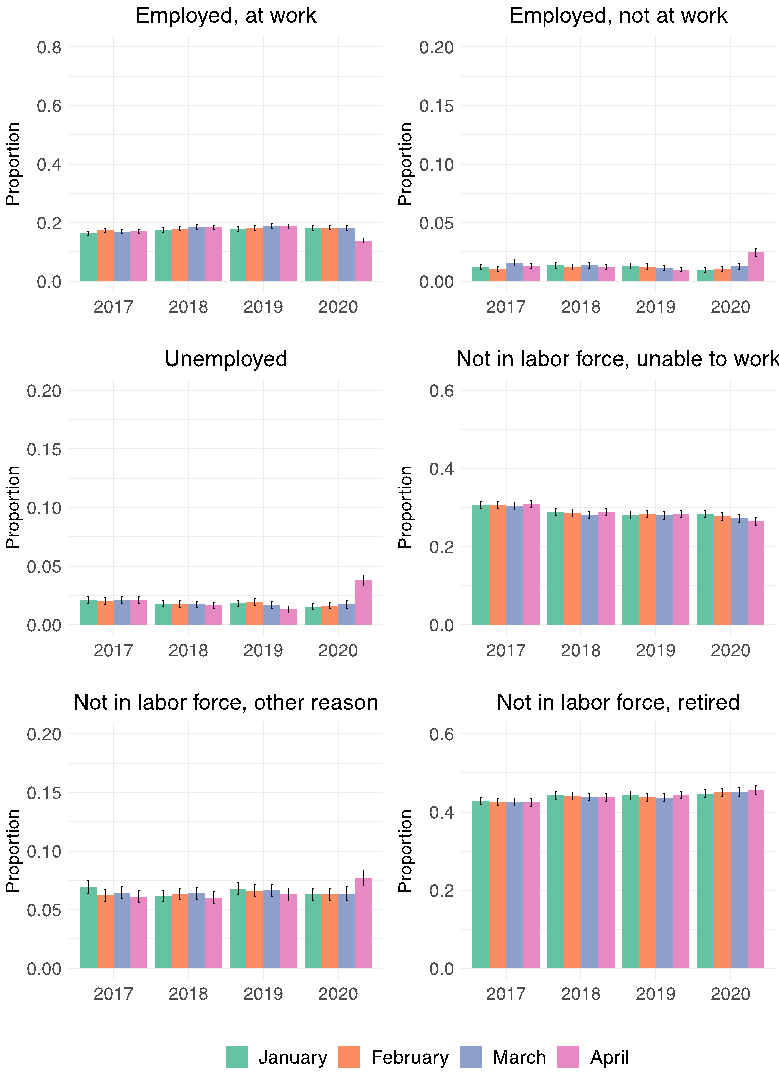

Employment data point to the economic consequences of COVID-19 for people with disabilities. As shown in Figure 2, employment levels among people with disabilities are already very low compared to the rest of the adult population. On average, between 2017 and 2020, less than 20 percent of adults with disabilities were employed and at work. Still, this number decreased from 18 percent to 14 percent between March and April 2020, resulting in a 24 percent decrease between these two months.

Figure 2 – Employment Status for Adults with Disabilities Age 18+ and Older, January-April, 2017-2020

Source: Basic Monthly CPS for January-April 2017-2020, N = 148,643 adults with disabilities (approximately 11,000 per month/year)

Notes: Error bars refer to 95 percent confidence intervals.

In addition, the percentage of adults with disabilities who were “employed, not at work,” rose from 1 percent to 2 percent between March and April, a 94 percent increase. The percentage who were unemployed increased by 117 percent, from 2 percent to 4 percent. Like the rest of the population, COVID-19 has meant increasing unemployment and work absences for people with disabilities. It has also meant movement out of the labor force.

Among those who are considered to be outside the labor force, the percentage of adults with disabilities who were unable to work decreased slightly (27.2 percent to 26.5 percent), and the percentage who were retired increased by a very small percentage (45.1 percent to 45.6 percent). However, estimates also show that the percentage of people with disabilities who were not in the labor force for other reasons increased by 21 percent, from 6 percent to 8 percent.

Disabled and vulnerable workers are now facing huge employment challenges

Most layoffs have occurred among low paying jobs where disabled workers often find themselves. Disabled workers disproportionality concentrated in low-paying food and service sector jobs are likely hardest hit by the coronavirus – sectors that have either seen total shutdowns or significant alterations to work. These also often include jobs that cannot be done remotely.

Those who continue to work may face longer shifts jeopardizing the necessary flexibility many people with disabilities require while potentially increasing exposure to the virus especially if they are in constant contact with the public. This can, in the long term, negatively affect health and result in lost work, wages and an even shakier financial future. It is also unclear how employers have continued to provide accommodations under social distancing measures at work – accommodations which allow people with disabilities to maintain work. Without adequate supports, these new work arrangements may lead disabled workers to reluctantly leave their jobs.

What’s certain is that the coronavirus and resulting social distancing measures have disproportionately affected already vulnerable groups. No doubt, the pandemic has generated new inequalities and new language around inequality that simply did not exist six months ago. At the same time, COVID-19 has exacerbated pre-existing inequalities already experienced by vulnerable groups like people with disabilities, bringing their existing economic marginalization into sharp relief.

COVID-19 is certainly making matters worse for those with disabilities. But the “post-COVID-19 era” – the so-called “reset” or “new normal” in how we conduct work will continue to negatively impact people with disabilities in drastic ways if we do not acknowledge and address the existing arrangements that have long marginalized this and other vulnerable groups.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/36kwjl5

About the authors

Michelle Maroto – University of Alberta

Michelle Maroto – University of Alberta

Michelle Maroto is associate professor of Sociology at the University of Alberta. Her teaching and research interests center on social stratification and extend to areas of gender and family, race and ethnicity, criminology, economic sociology, labor and credit markets, and disability studies. Her recent projects have focused on the causes and consequences of bankruptcy, wealth disparities in the United States and Canada, the effects of incarceration on wealth, and labor market outcomes for people with different types of disabilities. She is currently embarking on a new project that will examine dynamics of social class in Canada using survey and interview data.

David Pettinicchio – University of Toronto

David Pettinicchio – University of Toronto

David Pettinicchio is assistant professor of Sociology and affiliated faculty in the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. His new book, Politics of Empowerment: Disability Rights and the Cycle of American Policy Reform (Stanford University Press, 2019), investigates how and why seemingly entrenched policies like the ADA succumb to retrenchment efforts and the important role of both political elites and everyday citizens in mobilizing against these political threats.