Does the construction of new parks inevitably lead to nearby low-income neighborhoods becoming gentrified? It depends, find Alessandro Rigolon and Jeremy Németh. Studying different kinds of parks in ten US cities, they determine that function and location, not a park’s size, are linked to gentrification. Neighborhoods close to long, thin, centrally located parks like New York’s High-Line, are over 230 percent more likely to gentrify than other neighborhoods, while parks – both big and small – have little effect on poorer neighborhoods located at the edges of cities.

Does the construction of new parks inevitably lead to nearby low-income neighborhoods becoming gentrified? It depends, find Alessandro Rigolon and Jeremy Németh. Studying different kinds of parks in ten US cities, they determine that function and location, not a park’s size, are linked to gentrification. Neighborhoods close to long, thin, centrally located parks like New York’s High-Line, are over 230 percent more likely to gentrify than other neighborhoods, while parks – both big and small – have little effect on poorer neighborhoods located at the edges of cities.

Gentrification is affecting low-income people in urban communities worldwide. Many neighborhoods that have seen a lack of investment have experienced an influx of more affluent, college-educated residents, who over time contribute to increasing demand for housing and to displacing long-time, low-income residents, who are often people of color. But what jumpstarts such neighborhood change processes? There are numerous factors ranging from neighborhood desirability to the availability of relatively cheap housing in tight real estate markets.

In recent years, many scholars and activists have noted that environmental investments such as new parks have helped activate or accelerate gentrification in low-income neighborhoods in the US and other Global North countries. This “green gentrification” is particularly difficult to combat because parks represent good planning practice and because they are fundamental investments on which we build healthier and more resilient cities. But this doesn’t mean we should stop building parks. Not all new parks are created equal and knowing which types of parks are most often associated with gentrification can inform the work of urban planners, policymakers, and community advocates. For example, some scholars have argued that building small and scattered parks in lieu of large iconic green spaces, combined with strategies to protect affordable housing, can lead to “just green enough” outcomes wherein low-income communities can still enjoy the benefits of the new green city.

To understand which features of parks make them triggers of gentrification, we examined whether the location, size, and function of new urban parks can explain whether the gentrification-susceptible neighborhoods around them eventually gentrified. Gentrification-susceptible neighborhoods are US census tracts with household incomes below their city’s median. We expected that gentrification would occur more consistently around centrally-located parks, near larger parks rather than smaller or pocket parks, and around long, thin (linear) parks that include trails for active transportation, such as New York City’s High Line, Chicago’s 606 Trail, and Atlanta’s BeltLine.

The 606 (Chicago)

BeltLine (Atlanta)

We mapped the location of new parks built in 2000-2008 and 2008-2015 in ten US cities, including the five most populous cities (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Philadelphia) and five medium-sized cities experiencing rapid growth (Albuquerque, Austin, Denver, Portland, and Seattle). In our models, we controlled for a wide range of factors known to be associated with gentrification. To have actually gentrified, a neighborhood had to have experienced shifts in a number of demographic, socioeconomic, and housing variables at rates that outpaced changes at the broader city level over the same period.

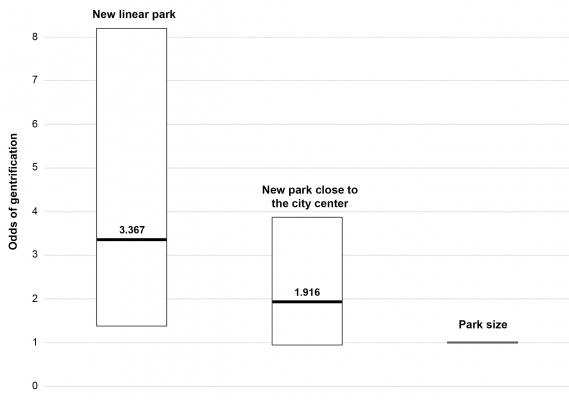

We found that, between 2008 and 2015, the function and location of new parks were associated with gentrification while size was not. New linear parks with active transportation trails were consistently linked to higher odds of gentrification in their surrounding neighborhoods. We also found that new parks built closer to city centers were more likely to foster gentrification than parks located farther away from downtowns. But the impact of linear parks was the strongest. Neighborhoods with a new linear park built within a half-mile of their center were 236 percent more likely to gentrify than other census tracts, even when controlling for a variety of demographic and environmental factors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Odds of gentrification for the three park variables in 2008-2015

Nevertheless, the size of new parks built in 2008-2015 showed no statistically significant association with the odds of gentrification in surrounding neighborhoods. This result casts doubts on claims that new small parks can lead to “just green enough” outcomes, as we found that new small parks, when located close to city centers, are indeed associated with gentrification. Finally, neither park location, size, or function were associated with gentrification between 2000 and 2008. This is likely due to the housing bubble in the 2000s, which might have trumped the effect of new parks, and to the very low number of new linear parks built in gentrification-susceptible neighborhoods during that same period.

Our findings suggest actionable initiatives for equity-oriented policymakers, planners, and community-based organizations. As cities worldwide are increasingly developing urban greening initiatives to tackle the challenges of climate change, we now know that linear parks and centrally-located parks are likely to spur gentrification and displacement if not accompanied by adequate anti-displacement strategies. A recent report suggests six different types of “parks-related anti-displacement strategies” through which cities and non-governmental organizations can help low-income communities become greener without paying the price of gentrification and displacement. Specifically, the construction of new linear parks and of new parks close to city centers should become part of gentrification early warning systems, which include a broad range of other desirability factors for low-income neighborhoods.

Our findings on park size suggest that building small parks fails to prevent nearby neighborhoods from gentrifying. When located close to city centers and other amenities, even small parks can play a role in starting or accelerating gentrification processes. But our findings on park size also suggest that policymakers, planners, and community organizations can build new large parks in park-poor, low-income communities located at the edges of cities without excessive risks of gentrification. These initiatives can help address historical inequities in access to parks that affect low-income people and people of color in the US and around the world.

The answer to the threat of green gentrification should not be, “let’s stop building parks in low-income communities.” Historically disinvested communities should not have to choose between a nice park and an affordable home. Several non-governmental organizations and cities around the US are implementing effective parks-related anti-displacement strategies. Nonprofit-led projects like the 11th Street Bridge Park in Washington, DC, partnerships between parks and housing nonprofits like the Los Angeles Regional Open Space and Affordable Housing (LA ROSAH) collaborative, and city-led park development efforts like San Francisco’s India Basin Shoreline Park are paving the way for more equitable green futures.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Green gentrification or ‘just green enough’: Do park location, size and function affect whether a place gentrifies or not?’, in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2oGMsQw

About the authors

Alessandro Rigolon – University of Utah

Alessandro Rigolon – University of Utah

Alessandro Rigolon is an Assistant Professor in the Department of City & Metropolitan Planning at the University of Utah. His research centers on planning for urban green space and health equity, covering three related areas: planning and policy determinants of (in)equitable park provision, drivers and resistance to green gentrification, and the health impacts of urban green space on marginalized communities. His research has appeared in Urban Studies, Landscape and Urban Planning, the Journal of Planning Education and Research, Cities, and Urban Geography. He co-authored Urban Green Spaces: Public Health and Sustainability in the United States.

Jeremy Németh – University of Colorado Denver

Jeremy Németh – University of Colorado Denver

Jeremy Németh is an Associate Professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Colorado Denver. His research looks at how planners, designers, and city dwellers can help create more socially and environmentally just places. He is particularly interested in the relationship between social equity and the built environment, and his recent work examines issues of disaster justice, transportation equity, and gentrification resistance. His work has appeared in Urban Studies, the Journal of Planning Education and Research, the Journal of the American Planning Association, Cities, and the Journal of Urban Affairs.