A dominant view in urban economics suggests that the solution to the housing crisis of major cities is to relax zoning and other planning regulations. Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and Michael Storper challenge this position, arguing that there is no clear and uncontroversial evidence that housing regulation is a principal source of differences in home availability or prices across cities and that these issues are more linked to rising inequalities in the geography of employment, wages and skills. Blanket changes in zoning are unlikely to increase affordability for lower-income households in prosperous regions but would increase gentrification without appreciably decreasing income inequality.

A dominant view in urban economics suggests that the solution to the housing crisis of major cities is to relax zoning and other planning regulations. Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and Michael Storper challenge this position, arguing that there is no clear and uncontroversial evidence that housing regulation is a principal source of differences in home availability or prices across cities and that these issues are more linked to rising inequalities in the geography of employment, wages and skills. Blanket changes in zoning are unlikely to increase affordability for lower-income households in prosperous regions but would increase gentrification without appreciably decreasing income inequality.

The housing affordability problem

Housing in the largest metro areas the world over has become unaffordable for much of the population. Hard working individuals living in large cities have been priced out of better-quality housing. Those wanting to move from lagging regions into dynamic urban areas in search of better opportunities are also deterred by astronomical real estate costs. Segregation and housing and income inequality are increasing, as are commuting times.

According to the dominant view in urban economics, the main culprit for this situation is restrictive zoning in large metro areas. The solution is simple: the massive upzoning of urban land by reducing the decision-making power of local communities over land use, so that they can no longer prevent high-density building. By getting rid of restrictions and letting the real estate developers in, more and more affordable housing will be built in the places where people have the greatest opportunities. Prosperous metropolitan areas, like New York, the Bay Area or London will become bigger, more productive, and more socially inclusive. Inter-regional mobility will pick up and, as a consequence, income inequality will decline, both within cities and across the country.

Supply restrictions are, therefore, considered to be the main obstacle to solving the problem. Zoning prevents building enough housing to keep up with demand, increasing housing prices, rewarding landowners, enhancing, as a consequence, inter-personal and inter-territorial income inequality and dissuading talent from flowing into the more affluent regions. It is also regarded as a main source of economic inefficiency, as lack of affordable housing may prevent these cities to reach their full potential, limiting overall national growth and hurting the most vulnerable.

Finding a possible solution

The solution is, according to this view, simple: cut regulation in order to build more and denser housing in metro areas. The greater affordability triggered by housing deregulation in the prime areas of prosperous metro regions would trickle-down to the rest of the metro area. Following this view, a fast growing coalition of high-income millennials (YIMBYs), urban planners who want density, developers, and elected officials has thrust this view into the public debate. Legislation is now actively promoting top-down deregulation and upzoning not just as a way to address the housing affordability problem, but also as a cure-all for low productivity and aggregate national growth as well as for both interpersonal and inter-territorial inequality. Nowhere is this rifer than in California, where Senate Bill 4 (McGuire and Beall 4/10/2019) states that “Economists widely agree that restrictive land use policies increase housing prices. Studies have found that housing prices in California are higher and increase faster in jurisdictions with stricter land use controls, and in some markets, each additional regulatory measure increases housing prices by nearly 5 percent. Stricter land use controls are also associated with greater displacement and segregation along both income and racial lines. Restrictive land use policies also hurt economic growth by preventing residents from moving to more productive areas where they can accept more productive jobs that pay higher wages.” SB 50 (Weiner et. al, as amended 11/03/19) states that the consequences of restrictive local housing regulations “are discrimination against low-income and minority households, lack of housing to support employment growth, imbalance in jobs and housing, reduced mobility, urban sprawl, excessive commuting, and air quality deterioration.”

What’s novel about this coalition is that it draws on mainstream housing economics and then claims that this new deregulationist market urbanism is socially and economically progressive. In like fashion, they consider those who oppose their endorsement of blanket upzoning to be self-centered NIMBYs, uninterested in justice, inclusion or equality, and who, they say, have caused the current crisis. YIMBYism can be seen as a generational clash between the younger segment of the top 30% who resent the existing (somewhat richer and older) segment of the top 30%, who occupy the neighbourhoods where the millennials would like to live but cannot, but who represent themselves as the avant-garde for the lower 70% of the population. The beauty of their solution to the housing and inequality woes of our cities is that it is straightforward: deregulate to allow more housing units on high-demand existing lots, and when the market generates higher buildings in the most lucrative neighbourhoods, wait for the benefits to trickle down the social and geographical ladder.

Is this too good to be true?

Does this sound too good to be true? In a new paper on the limits to deregulation and upzoning in reducing economic and spatial inequality, we argue that this is, indeed, too good to be true. The authors posit that the background to understanding the housing crisis is not just zoning, but the decades-long rise in income inequality and the return of high-wage jobs to cities, a toxic combination of high overall demand with high-inequality and insufficient housing purchasing power on the part of much of the population. The paper argues against those proposing blanket deregulation and upzoning in two main ways.

First, the evidence on trickle-down benefits is weak to non-existent. The intra-urban housing markets in cities are highly segmented. This means that the interest in prime land in the downtowns and job, transit, and amenity-rich areas is far greater than in virtually all other urban land. There are considerably more benefits to be made by building in these areas than in more distant and less accessible locations. There are also far greater benefits to be made by targeting the upper- than the middle- or lower-end of the housing markets. It comes therefore as no surprise that in virtually all processes of inner-city upzoning the first new constructions are luxury condos in some of the most desirable areas of the city. The buyers of these properties end up being generally affluent local workers at the top of the salary scale, wealthy suburbanites who want a pied-à-terre in the city, institutional investors, part-time residents, or, in cases like London and New York, foreign oligarchs.

More high-end housing supply might be welcome if it triggers a trickle-down effect that is big enough to help wide swathes of the population in wide swathes of neighbourhoods. How could this occur? The consumers of the new high-priced housing in desirable locations would have to “filter” out of these other neighbourhoods and hence soften demand enough in them so that prices in the housing markets for lower income groups would become substantially lower and their housing upgraded. The problem for this claim is that even the academics who find some filtering also find it occurs almost entirely within the already high-priced areas. The higher-income people are just moving up within their areas. This isn’t trickle down but attending to the privileged.

This is why, in most previous cases where widespread upzoning has taken place, the same story is repeated: supply expands and the cost of housing for the upper income segment declines, while having little to no positive effect for the rest of the population.

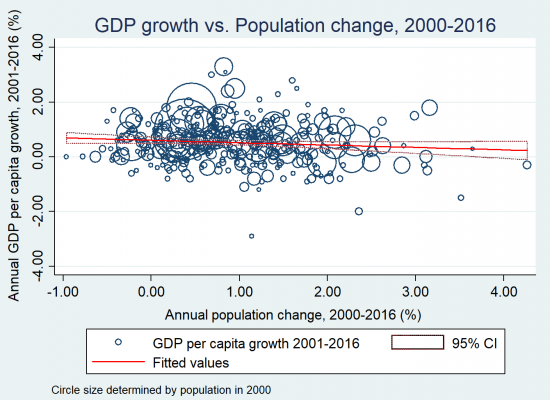

Second, a key claim by those positing blanket deregulation is that selfish elites in dynamic metro-regions are not just creating a local problem, but a national one, by keeping people from less dynamic places from moving in. Yet, taking the case of the US, the link between population change and GDP growth has, in recent years, been non-existent (Figure 1). Many large American cities with relatively lax planning regulations are indeed growing fast. Between 2010 and 2018 the population of Orlando grew by 20.5%, that of Houston by 18.2%, Dallas-Fort Worth by 17.3%, Phoenix by 15.8%, and Atlanta by 12.5%. But Seattle (14.5%), Portland (11.4%), Washington, D.C. (10.9%) also grew in double digits, despite much greater planning restrictions. The Bay Area increased its population by 9.1% (which in absolute terms represents 500,000 additional inhabitants in Seattle and 400,000 more in the Bay Area in a mere eight years). But another big difference is that while annual GDP growth per capita in restrictive San Jose between 2001 and 2017 was 3.5% and 2.5% in Portland, GDP per capita growth in less restrictive places, such as Atlanta, Orlando or Las Vegas was negative, or a paltry 0.03% in Phoenix and 0.36% in Houston.

Figure 1 – Link between population growth and the growth of GDP per capita in US MSAs, 2000-2016

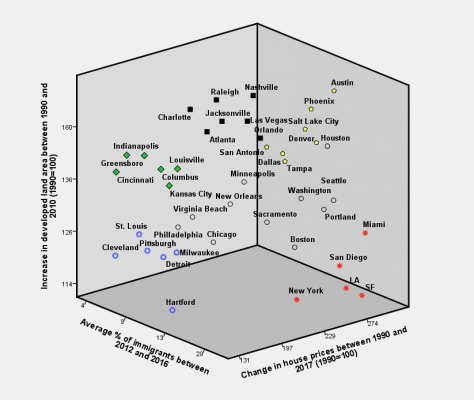

No amount of affordable housing in the Bay Area, London or Frankfurt can facilitate the job market integration of a high school graduate from, say, Youngstown (Ohio), Sheffield, or Chemnitz, respectively. The problem in this respect lays not in housing unaffordability, but in education systems that leave so many people behind, while prosperous metro areas concentrate jobs in the industries requiring the most education. Figure 2 buttresses the view that it is the fundamentals of economic geography more than house prices that are at work, by showing the weak relationship between changes in home values, expansion of the developed residential area, and the presence of immigrants in US cities.

Figure 2 – Urban land area development, house prices and in-migration in the largest metropolitan areas in the US (1990-2017)

Toward more carefully-targeted upzoning as a solution

Hence, blanket upzoning is likely to end up adding further within-city spatial segregation to what are already rife interpersonal inequalities. Just as neglecting rising territorial inequalities has unleashed populism across the developed world, ignoring the spatial consequences of upzoning is a recipe for future social troubles, leading to less, not more economic growth.

In other words, carefully-targeted – not blanket – upzoning may ultimately be part of a delicate and complex policy mix that is required to address inequalities both within our cities and across our regions. This mix includes at least combining education, social, health and housing policies. And in the realm of housing policy this will mean more and different types of regulation, that may neither appeal to YIMBYs, nor to NIMBYs.

- This article first appeared at VoxEU and is reposted with permission.

- Featured image: Photo by Yancy Min on Unsplash

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/37SWT51

About the authors

Andrés Rodríguez-Pose – LSE Department of Geography and Environment

Andrés Rodríguez-Pose – LSE Department of Geography and Environment

Andrés Rodríguez-Pose is a Professor of Economic Geography at the London School of Economics, where he was previously Head of the Department of Geography and Environment. He is the Acting President of the Regional Science Association International, where he served as Vice-President in 2014. He has also been Vice-President (2012-2013) and Secretary (2001-2005) of the European Regional Science Association. He is a regular advisor to numerous international organizations, including the European Commission, the European Investment Bank, the World Bank, the Cities Alliance, the OECD, the International Labour Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Development Bank of Latin America.

Michael Storper – LSE Department of Geography and Environment, UCLA

Michael Storper – LSE Department of Geography and Environment, UCLA

Michael Storper is an economic geographer who holds concurrent appointments UCLA, the London School of Economics, and Sciences Po/Paris. Storper is the author of more than 100 peer-reviewed academic articles and 13 books, including the widely-cited The Regional World: Territory, Technology and Economic Development (Guilford), Worlds of Production (Harvard), and Keys to the City (Princeton University Press, 2013). His most recent book (2015) is entitled The Rise and Fall of Urban Economies: Lessons from Los Angeles and San Francisco (Stanford University Press).