In The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to the Civil War, Joanne Freeman examines the increase of violence in the US Congress experienced from the 1830s to 1861 in the build-up to the US Civil War, a period that witnessed the rise of the mass political party and growing opposition to slavery and the power of the Southern planters in national affairs. This is a well-researched, pacey and enlightening account of how the American polity developed and fragmented within the close quarters of its central institution, writes Ben Margulies.

The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to the Civil War. Joanne Freeman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2018.

US historians and polemicists have long tied the country’s high levels of violence to its history of white supremacy. Michael Moore made this connection explicit in Bowling for Columbine, while Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz examines how private and public violence advanced the dispossession of Native Americans. Edward Baptist argues that violence was an indispensable technology of slavery and the Southern cotton industry that so ruthlessly employed it, while Michael Bellesiles finds that the post-Civil War South was far more violent than the ‘Wild West’. The South remains the most violent part of the United States even today.

That heritage of violence is one of several reasons why Joanne Freeman’s The Field of Blood is such a relevant work for our time. The book also deals with questions of representation, identification and collective status that echo through modern politics, sometimes deafeningly.

Freeman’s study is a sort of ethnography of the US Congress between the 1830s and 1861, when the Civil War began. This period encompasses two major phenomena. The first is the rise of the mass political party, pioneered by Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party, and the second is the growing sectional controversy over slavery, its morality and the power of the Southern planters in national affairs.

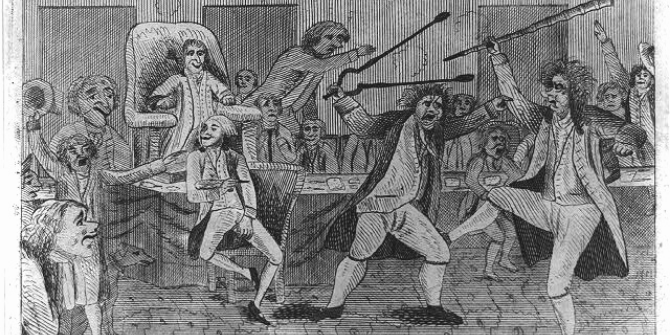

Freeman examines these tensions through perhaps their most overt micro-level manifestation, which is the endemic violence that marked the Congresses of this period. Much of this violence was verbal: ‘personalities’ (personal insults), bullying and threats made up much of the texture of Congressional life. But quite often open violence broke out on the floor or in Washington’s streets, hotels and boarding houses. Freeman’s book details fist-fights and duel challenges as well as members threatening each other with weapons on the floor. Freeman writes about not one but two altercations between an armed Louisiana congressman, John Dawson, and anti-slavery champion Joshua Giddings of Ohio; in the first, Dawson brandished a knife, and in the second he ‘cocked his pistol, bringing four armed Southern Democrats to his side’ (70). Violence often occurred outside the Capitol: one former congressman, Sam Houston, caned a US representative on Pennsylvania Avenue (18). (Houston went on to serve two terms as President of an independent Texas.)

Image Credit: ‘Congressional pugilists’, 1798. A crude portrayal of a fight on the floor of Congress between Vermont Representative Matthew Lyon and Roger Griswold of Connecticut (Library of Congress, No Known Copyright Restrictions)

Image Credit: ‘Congressional pugilists’, 1798. A crude portrayal of a fight on the floor of Congress between Vermont Representative Matthew Lyon and Roger Griswold of Connecticut (Library of Congress, No Known Copyright Restrictions)

Members threatened duels, and a federal anti-duelling law was passed in 1839, a year after a fatal encounter between two members of the House, William Graves of Kentucky and Jonathan Cilley of New Hampshire. Freeman devotes a whole chapter to the Graves-Cilley duel, which illuminates many of the key themes of her work, all of which resonate powerfully today.

The first is the close identification between representative and the represented, whether these are defined by state, party or region. Every insult and threat in Washington was treated as an insult and menace to the constituent’s home state, and to the North or South as a whole. Freeman describes Congressman Graves’s thinking before his duel: ‘Dishonor him and you dishonour all that he represented […] for the honor of himself, his constituents and Kentucky, Graves felt that he couldn’t let Cilley’s implied insult slide’ (94).

These loyalties could extend also to the growing mass parties and their leaders. ‘Party membership was more than a label; it was a kind of pledge, a statement of loyalty to a political worldview that bound men together in reputation and purpose’ (10-11). For Democrats, this meant identifying the Democratic Party with the Union, and both with the father of the party, Andrew Jackson (58). These sorts of identifications prefigure the modern populist equation of leader-party-nation: indeed, Donald Trump has stated an admiration for Jackson more than once. (Freeman notes that Jackson’s appeal was to the ‘white common man’ (19, original emphasis).

Freeman’s work also refers to the ways that racial politics shaped the culture of violence in the United States, especially as the country’s politics and parties reoriented around the question of slavery and its expansion. Southern violence – as Northern critics frequently pointed out – was tied to the way that plantations and enslaved people were governed. ‘By definition, a slave regime was violent and imperilled’ because of the threat of revolution (70), and thus Southerners reacted violently to any suggestion of or advocacy for abolition as a threat to their lives and their honour. This endemic violence also produced a South that embraced a culture of duelling and private violence (‘such man-to-man encounters were semi-sanctioned in the South’ (70)).

Northerners, on the other hand, rejected duelling and perceived Southern objections – correctly – as bullying. Worse, it denied Northerners their rights: ‘The very act of speaking in the face of howling resistance was a declaration of Northern rights, because it asserted the right of free speech on the floor [of Congress]’ (211). The Civil War was fought over slavery, but in large part because Northerners perceived the ‘Slave Power’ as oppressing not just African Americans, but the citizenry in general. This fear of being denigrated and humiliated, especially by elite figures – a sentiment which reappears over and over again in the sources Freeman cites – speaks powerfully to contemporary politics.

Freeman’s narrative is especially strong in describing the final years before the Civil War. In the final pre-war Congresses violence grew more common, and members increasingly came armed. Southerners frequently threatened to seize the chamber by armed force. ‘Many congressmen strapped on knives and guns each morning as they headed off to Congress, and their number was growing; Northerners had been urging their representatives to arm since [Sen. Charles] Sumner’s caning [in 1856]’ (249).

Sumner’s caning is perhaps the most famous act of Congressional violence of this era. Sumner, who represented Massachusetts, made a famously piercing attack on pro-slavery forces during the ‘Bleeding Kansas’ unrest. Sumner’s words prompted Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina (a cousin of one of Sumner’s targets) to savagely attack him on the Senate floor. This notorious assault – which left Sumner recovering from his injuries for more than three years – often appears in standard histories and textbooks, and Freeman gives an interesting new perspective on the attack and the way it both fitted with and transgressed the rules of the time.

Freeman’s book is exceptionally well researched. Her examination of journalistic records and diaries is thorough, and her explanations about how journalists covered Congress are fascinating enough for a book in its own right. Freeman explains how the most widely circulated press record, the Congressional Globe, frequently omitted or bowdlerised accounts of Congressional violence, as did Washington papers in general, partly because DC papers relied on federal printing contracts (186-87). The development of a national press and the telegraph produced a more open reporting, and tended to heighten the cycle of violence.

Freeman’s style is rather breezy and conversational for an academic history, which (for a snobbish academic like myself) can be occasionally off-putting. At one point, she refers to John Quincy Adams – the sixth President, then a Congressman, and an irascible opponent of slavery – as ‘clearly, Fight Consultant Extraordinaire’ (35)). That said, her subject does lend itself to comedy at times: for example, an 1858 melee in the House ended in part because one member accidentally yanked off Congressman William Barksdale’s hairpiece. Freeman’s reference to ‘the hilarity of Barksdale’s flipped wig’ (240) seems apropos.

Freeman’s informal tone partly reflects the way she has chosen to frame her narrative. She uses Benjamin Brown French, a New Hampshire Democrat-turned-Republican who served as clerk of the House, as a sort of viewpoint character, in large part because French was an avid diarist. It helps that French was a friend to almost every senior figure in American politics, including Franklin Pierce, the fourteenth President of the United States. He also knew Abraham Lincoln: Freeman provides a photo of French taken at the dedication of the Gettysburg national cemetery (the occasion of the Gettysburg Address), in which he stands behind the President (276).

I would have liked more examination of the roles of race, violence and humiliation beyond Congress, especially the ways that violence was central to the governance of the South during (and after) slavery. But overall, this is a well-written, pacey and enlightening account of how the American polity developed and fragmented within the close quarters of its central institution.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2YUEIIp

About the reviewer

Ben Margulies – University of Brighton

Ben Margulies is a lecturer in political science at the University of Brighton. He was previously a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Warwick. He specialises in European, comparative and party politics.

Find this book:

Find this book: