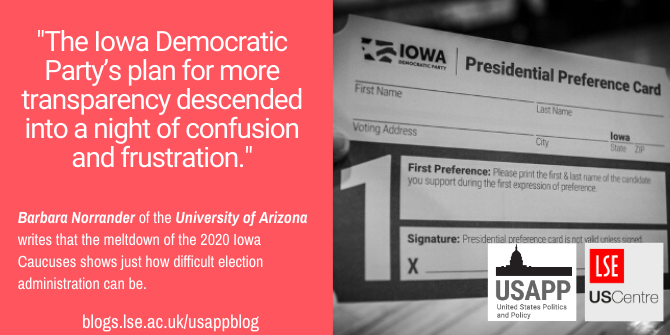

Last week, the 2020 Iowa Democratic Caucus suffered a ‘meltdown’ as difficulties with a new app for reporting the results led to long delays for the release of the contest’s results. Barbara Norrander looks at how caucuses are different to the primaries that make up most of the upcoming election calendar, why election rules matter, and why we shouldn’t always expect clear winners and losers from each contest.

Last week, the 2020 Iowa Democratic Caucus suffered a ‘meltdown’ as difficulties with a new app for reporting the results led to long delays for the release of the contest’s results. Barbara Norrander looks at how caucuses are different to the primaries that make up most of the upcoming election calendar, why election rules matter, and why we shouldn’t always expect clear winners and losers from each contest.

- This article is part of our Primary Primers series curated by Rob Ledger (Frankfurt Goethe University) and Peter Finn (Kingston University). Ahead of the 2020 election, this series explores key themes, ideas, concepts, procedures and events that shape, affect and define the US presidential primary process. If you are interested in contributing to the series contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

The failure of a new app for reporting vote totals from 1,678 precinct caucuses to the Iowa Democratic Party led to the “Iowa Meltdown” last week. Thus, Iowa Democrats were unable to release results as the February 3 caucuses concluded. Iowa Democrats made mistakes, both in using an untested app and in releasing partial results in the days that followed. It also is apparent that not all caucus reports were consistent across the three reported totals: candidate support in the first round to determine which candidates met the 15 percent threshold to stay in contention, candidate totals in the second round after supporters from those who did not reach the threshold switched their backing, and the translation of candidate support into state convention delegates in what Iowa Democrats term “state delegate equivalents,” or SDEs. So, what are the lessons to be learned from the Iowa caucus meltdown?

Quality election administration is difficult

The Iowa caucuses are conducted by volunteers. Volunteers check registered Democrats into the caucus site, and with Iowa’s Election Day voter registration law, other volunteers register voters. Each of the 1,678 precinct captains is a volunteer. While these volunteers received training, it is apparent that a few made mistakes in the conduct of the caucuses and in the more complicated reporting requirements. Precinct chair provide instructions to caucus attendees on establishing support for their favorite candidate, on who could switch candidate support in the second round, and how to fill out the candidate preference cards. Many attendees pay attention to the precinct chair, but others continue to chat with those sitting next to them.. At the caucuses the only oversight is by other volunteers who represent each of the candidates.

Good intentions produce unexpected consequences

The 2020 Iowa caucuses included several changes to increase the transparency of the delegate selection process. But these new transparency rules put a larger burden on the precinct captains. In past years, the Iowa Democratic Party released only the state delegate equivalents. In 2020, the Iowa Democratic Party would release three caucus results. To be able to accurately report these three totals, another 2020 innovation provided each caucus attender with a two-sided “presidential preference card.” On the first side of the card, attendees would write their initial candidate choice and sign the form. If their first-choice candidate met the 15 percent threshold, these attendees were instructed to hand in their cards. For those whose first-choice candidate did not meet the 15 percent threshold for viability, these caucus attendees would write their first-choice candidate preference on one side of the card and after joining another candidate’s supporters would write that candidate’s name on the second side of the card. All caucus attendees were instructed to hand in the preference cards, but some may have left without doing so. Counting both an initial round of voting and a second round after a realignment meant final results for a local precinct might not be available until 9 p.m. or later. Afterwards, precinct captains who kept the tally from these two rounds of voting calculated the number of SDEs per candidate using instructions provided by the state party. Finally, the precinct captain was to transfer these three totals to the state party using the app, and when that didn’t work were frustrated by backup phone lines being jammed. The Iowa Democratic Party’s plan for more transparency descended into a night of confusion and frustration.

A second innovation for the 2020 Iowa caucuses with a good intention failed to materialize. Caucuses are often criticized because they are held at a specific date and time, usually a weeknight, when some may not be able to attend due to work or childcare conflicts. Unlike primary elections, caucuses have no provisions for absentee voting. Thus, for 2020 Iowa Democrats intended to hold virtual caucuses for those unable to attend the weeknight caucus, but security challenges proved to be too daunting. Instead, for the first time in 2020 the Iowa Democrats set up 87 satellite caucuses for registered Iowa voters to participate at 60 sites within Iowa, 24 locations across 13 US states and Washington, D.C, and three satellite caucuses held in foreign countries.

Credit: “Des Moines Precinct 61” by Phil Roeder is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The good intentions of local government officials can also produce unintended consequences. Before the 2016 presidential primaries in Arizona, county election officials in Phoenix introduced regional voting centers, which allows voters to cast a ballot at the most convenient center rather than at an assigned precinct site based on their home address. Voters like the idea of voting centers over precinct voting, and they reduce the cost of election administration that is often borne by local governments. Nevertheless, the roll out of these voting centers in Phoenix caused confusion and long lines. The infamous 2000 Palm Beach County, Florida, butterfly ballot also was introduced by a county official with good intentions. With many elderly residents in the county, the election official increased the font size used for listing presidential candidate names, which changed the format of the ballot. Subsequent confusion led a number of Democratic voters to inadvertently vote for Reform Party candidate Pat Buchanan instead of Democrat Al Gore.

Election rules matter

Many of the seemingly complicated rules of the Iowa caucuses come from national Democratic Party rules that apply to both primaries and caucuses. The purpose of both caucuses and presidential primaries is to select delegates to attend the July 13 – 16 Democratic National Convention where the party’s nominee will be officially chosen by a majority vote of the delegates. The national Democratic Party allocates delegate slots to the 50 states, Washington, D.C. and US territories. State delegate allocations account for state population size and past support for Democratic candidates. One-fourth of a state’s delegates are chosen on the basis of the statewide candidate vote totals and three-fourths based on outcomes in the congressional districts. Within each state, a specific number of delegates are assigned to each congressional district again based on population size and past support for Democratic candidates. Yet, these predetermine congressional-district delegate totals will not account for varying turnout across geographic areas. Thus, variation in turnout across Iowa’s local caucuses can account for differences between candidate support in the second-round count and the number of SDEs won. Yet, variations in turnout also are not accounted for in the Electoral College (used in presidential elections) where the number of each state’s Electors are set based on the previous US census. Each state casts its assigned number of Electors whether the state has a high or low turnout rate. In the 2016 presidential election state turnout rates varied from a low of 43.2 percent of the voting eligible population in Hawaii to a high of 74.7 percent in Minnesota.

Other states have changed their 2020 presidential nomination rules

Iowa is not the only state to introduce new voting procedures for this year’s elections. Four traditionally caucus states will be conducting party-run primaries instead. Three of these states (Alaska, Hawaii, and Kansas) and the Wyoming caucuses will use ranked choice voting. Instead of voting for only one candidate, which will be true in the state-run primaries, voters in these four states will be able to rank between three and five candidates. If their top choice fails to reach the 15 percent threshold, their vote will be transferred sequentially to one of their lower choice candidates. After each round of voting, one by one the candidate with the lowest vote total will be eliminated, until all remaining candidates have reached the 15 percent threshold for winning delegates. The state’s delegates will then be awarded proportionally among these remaining candidates.

Don’t expect instantaneous primary results

The Iowa Democratic Party adopted an app in part to produce a faster compilation of caucus results. Yet, all election night results are preliminary. This is especially true in states where many voters cast their ballots through the mail. In 2020, presidential primaries will be held in states with all mail-in ballots (e.g., Oregon and Washington) and in states where most voters opt to vote by mail (e.g. Arizona and California). Mail-in ballots take a longer time to process, as signatures must be verified before ballots are counted. States vary when ballots must arrive at county offices. Some states require that ballots arrive at county offices by Election Day. In contrast, California only requires that mail-in ballots be postmarked by Election Day. Thus, several 2020 presidential primaries may have ballot counting that extends for a week or more beyond Election Day. Furthermore, the leading candidate on election night may not be the leading candidate after the final vote count.

Not all primaries and caucuses have clear winners (or losers)

Candidates are eager to claim the slightest of leads in hopes of influencing the outcome of subsequent events, and the 24/7 media is eager for the latest piece of election news. Yet, some primaries and caucuses produce essentially tied outcomes. The best interpretation of the results of the 2020 Iowa caucuses is a tie between Pete Buttigieg and Bernie Sanders in terms of state delegate equivalents won. Such tied outcomes occurred in past nomination contests, as well. In the 2012 Republican Iowa caucuses Mitt Romney posted a caucus-night lead of 8 vote over Rick Santorum, only to have a later recount awarding a 34-vote margin victory to Santorum. Missouri’s 2016 presidential primary produced tied outcomes for both Republicans and Democrats: 40.8 percent for Donald Trump versus 40.6 percent for Ted Cruz; 49.6 percent for Hillary Clinton versus 49.4 percent for Sanders. Trying to declare a winner in such circumstances is a misleading exercise in splitting hairs. Even slightly greater differences between candidates will not produce meaningful differences in the number of delegates won under the Democratic Party’s proportional representation rules.

As the contests continue, we should not over interpret the results of any one primary or caucus

The media and the American public should not put so much emphasis on the results of one event, such as the Iowa caucuses. Democratic nominating events occur across 50 states; Washington, D.C.; five territories; and Americans Abroad. The last delegate selection events occur on June 2, when four states and Washington, D.C. hold their primaries and June 6 when the Virgin Islands holds it caucuses. The front four states (Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina) represent different elements of the Democratic Party and each should be viewed as a sampling of the strengths and weakness of candidates among different components of the party. There is no need to rush to judgement about the ultimate outcome of the presidential nomination, especially since the front four states select only 4 percent of the Democratic delegates.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/39tncir

About the author

Barbara Norrander – University of Arizona

Barbara Norrander – University of Arizona

Barbara Norrander is a professor in the School of Government and Public Policy at the University of Arizona, where she specializes in electoral politics. Her most recent book is The Imperfect Primary: Oddities, Biases, and Strengths of US Presidential Nomination Politics, 3rd edition (Routledge, 2020).