In the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election, all 50 states will hold either primaries or caucuses to select the presidential nominees for the Republican and Democratic parties. Barbara Norrander outlines how presidential primaries and caucuses operate, who can vote in them, and how they may be different in 2020 compared to past elections.

In the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election, all 50 states will hold either primaries or caucuses to select the presidential nominees for the Republican and Democratic parties. Barbara Norrander outlines how presidential primaries and caucuses operate, who can vote in them, and how they may be different in 2020 compared to past elections.

- This article is part of our Primary Primers series curated by Rob Ledger (Frankfurt Goethe University) and Peter Finn (Kingston University). Ahead of the 2020 election, this series explores key themes, ideas, concepts, procedures and events that shape, affect and define the US presidential primary process. If you are interested in contributing to the series contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

Unlike the UK and most of Europe, many elections at the state and national level in the United States are preceded by a primary election to choose the candidate who will contest the general election for a particular party. In presidential primaries and caucuses, every four years voters select the delegates from their state who will attend the Democratic and Republican national conventions. However, the national importance of presidential primaries, and to a lesser extent caucuses, is that they provide a battleground between competing candidates. Candidates who win a series of primaries gain momentum; candidates who do not fare well drop out of the race. In most nomination races, somewhere between March and early May, all but one candidate drops out. The remaining candidate becomes the party’s presumptive nominees and is officially nominated at the party’s national convention in early summer when a roll call of states reveals that a candidate has the support of a majority of delegates.

How do presidential primaries in the US work?

The legal purpose of the primaries and caucuses is important even before the conventions. Various media reports keep count of delegates won by each candidate. These delegate counts signal who is most likely to be the nominee and convince candidates lagging behind to end their bid for the nomination. So how is delegate selection connected to presidential primaries and caucuses? The two national parties allocate a number of delegates to each state. These allocation strategies differ across the two parties, but each accounts for a state’s population size and patterns of past support for that party’s candidates. In the Democratic Party three-fourths of a state’s delegates are chosen on the basis of candidates’ support in congressional districts, while the other fourth are selected based on the statewide vote. The Republican Party awards 10 statewide delegates to each state, plus more for prior party support, and adds three delegates for each congressional district.

The Democratic Party uses proportional representation to distribute a state’s delegates to candidates that win support in presidential primaries and caucuses. A candidate needs to win 15 percent of the vote to be awarded any delegates. In 2016, the Republican Party required proportional representation rules for primaries held before March 15. States scheduling primaries after that date could use a variety of rules. Although it is a common impression that many Republican presidential primaries are winner-take-all, where the candidate with the most votes wins all of a state’s convention delegates, only eight states in 2016 used a simple winner-take-all formula. Other states used winner-take-all only if a candidate won a majority of the vote or used a different formula for awarding delegates at the district versus state level. Many states used some form of proportional representation either at the state level or congressional district level.

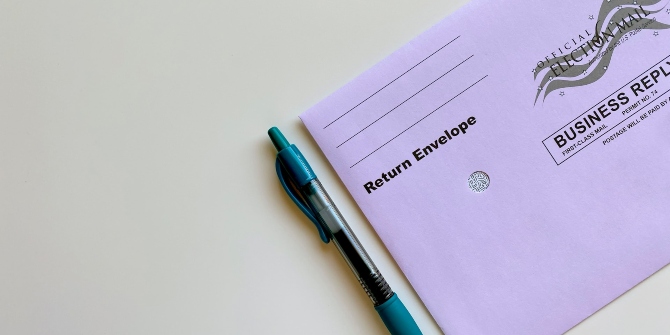

In presidential primaries, voters cast a ballot for their favored candidate. Results of these votes are tabulated at the state and congressional district levels to determine the number of delegates each candidate should be awarded. The people who become delegates are typically selected after the primary. Presidential primaries are conducted by state and local governments in the same manner as most US elections. Voters cast ballots at the polls on primary election day, or as is the case in an increasing number of states, voters may receive and return a ballot by mail.

“2016-06-07 i voted” by Robert Couse-Baker is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Who votes in presidential primaries?

Who can actually vote in a primary is determined by state law. Closed primaries restrict participation to those who registered as a partisan on their voter registration form. In semi-closed primaries, registered partisans are confined to their own party’s primary but registered independents can choose either party’s primary. In open primary states party preference is not asked on the voter registration form. Voters select a party’s primary at the polling place. While many believe primary participation rules affect the composition of the electorate or the outcome of the primary, this is generally not true. Voters across open and closed primaries have similar issue and ideological positions, and crossover voters in open primaries rarely affect the outcome.

Turnout in the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries averaged 35 percent, while for Republican primaries it was 31 percent. While these percentages appear to be low, turnout in the 2016 presidential election was 60 percent of the voting eligible population. Political science research finds primary voters are a good match to general election voters. One reason is the 65 percent of presidential election voters also voted in a presidential primary based on validated voter records in the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study. Thus, the typical presidential election voter is also a presidential primary voter.

So, what is a caucus, and why are they less popular?

Caucuses are a more complicated process. Caucuses are a local party meeting that the public may attend. In typical presidential election years, about a dozen states use caucuses to select their convention delegates. The local caucus is the first step in a series of meetings. Take the case of Iowa Democrats in 2016. Precinct caucuses were held on February 1, which selected delegates to attend county conventions held on March 12. County conventions picked delegates for both congressional district and state conventions. Congressional district conventions, held on April 30, chose district-level delegates to attend the Democratic National Convention. Iowa’s statewide delegates were selected at the June 18 state convention.

Democratic and Republican caucuses have separate rules. In Republican caucuses, participants typically express their candidate preference in an entrance poll. As of 2016, results of the entrance poll were binding on subsequent delegate selection. In Democratic caucuses, two rounds of voting are possible. In the initial round, supporters of each candidate are identified, often by each candidate’s supporters moving to a different part of the room. If the number of a candidate’s supporters is less than the 15 percent threshold, supporters of this candidate may switch their vote in the second round. Vote totals in the second-round are used to proportionally distribute county-convention delegate slots to each candidate’s supporters. Local caucus meetings are conducted by local party volunteers. Defenders of caucuses view them as the epitome of grassroots politics, where neighbors come together to discuss political issues and candidates. Yet, many attendees come with a predetermined candidate choice, and many also leave the caucus once candidate delegate totals are calculated.

Caucuses typically receive less attention from candidates, media and voters. The exceptions are the Iowa and Nevada caucuses, which are part of the first four events, along with the New Hampshire and South Carolina primaries. US states holding caucuses typically have smaller populations and consequently, low numbers of convention delegates. Due to the difficulty of organizing a campaign around multiple caucus sites and with few delegates at state, most presidential nominee seekers ignore caucus states. When candidates ignore a caucus, so does the media.

Because of the time commitment – they take several hours and are often held on weekday evenings – and open voting on the Democratic side, turnout in caucuses is quite low, averaging 9 percent in 2016 Republican caucuses and 8 percent for Democratic caucuses. Many voters are unwilling to attend a political meeting for that length of time, and some are unable to attend due to work or childcare issues. Overall, the American public is not fond of the caucus format with less than 20 percent viewing caucuses as fairer than primaries. Perhaps with that in mind, some changes are in place for caucuses in 2020. First, fewer states will hold them. Second, Democratic caucuses will need to adopt procedures for absentee participation.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2GTcxmT

About the author

Barbara Norrander – University of Arizona

Barbara Norrander – University of Arizona

Barbara Norrander is a professor in the School of Government and Public Policy at the University of Arizona, where she specializes in electoral politics. The third edition of her book, The Imperfect Primary: Oddities, Biases, and Strengths of US Presidential Nomination Politics (Routledge) will be available later this year.