This week President Trump placed his thumb on the scales in the sentencing of his past associate Roger Stone Jr, who had been convicted of obstructing justice, lying to Congress and threatening a witness with bodily harm, last November. Toni Locy writes that Trump’s pressure, which led to the resignation of four prosecutors involved in the case, shows the fluidity of federal sentencing, despite long-agreed guidelines which were created with bipartisan support.

This week President Trump placed his thumb on the scales in the sentencing of his past associate Roger Stone Jr, who had been convicted of obstructing justice, lying to Congress and threatening a witness with bodily harm, last November. Toni Locy writes that Trump’s pressure, which led to the resignation of four prosecutors involved in the case, shows the fluidity of federal sentencing, despite long-agreed guidelines which were created with bipartisan support.

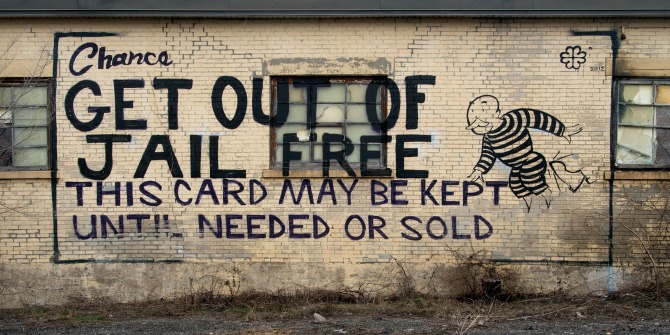

Life imitates art, and there is no better example than the drama surrounding the prosecution of US President Donald Trump’s confidant Roger Stone Jr. Over the past few days, key players in the case have acted out their interpretations of the iconic Godfather movies’ themes of power, respect, greed and vengeance.

Last November, a federal jury convicted Stone, 67, of obstructing justice, lying to Congress and threatening a witness with bodily harm. Trial testimony revealed how Stone bragged that he had inside information about WikiLeaks’ plans for release of hacked Democratic Party emails during the 2016 election—and then lied about it to Congress.

In a court filing on February 10th, prosecutors described how Stone quoted mob characters and mimicked scenes from The Godfather saga in urging a federal judge to lock him up in prison for 7 to 9 years when he is sentenced on February 20th.

Hours later, in the middle of the night, Trump tweeted, “This is horrible and unfair. The real crimes are on the other side, as nothing happens to them. Cannot allow this horrible injustice.”

In a plot twist, senior officials at the Justice Department then told a federal judge to disregard the 7-to-9-year prison recommendation made by the prosecutors who had directly handled Stone’s case. Instead, the senior officials said their underlings had miscalculated and that Stone’s sentencing range is 37 to 46 months.

Trump applauded, tweeting: “Congratulations to Attorney General Bill Barr for taking charge of a case that was totally out of control and perhaps should not have been brought.”

“Prettyman Court House” by Adam Fagen is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

Within hours, four career prosecutors withdrew from the case. Scholars and former federal prosecutors joined Democrats in denouncing Trump, Barr and other senior Justice officials. The New York Times editorial board accused administration officials of abusing their power by “wielding law enforcement for private ends, whether to attack their enemies or protect their allies.”

Faced with a credibility crisis among his staff, Barr demanded respect, from all critics, including Trump. In an interview with ABC News, he said the president’s tweets “make it impossible for me to do my job and to assure the courts and the prosecutors in the department that we’re doing our work with integrity.”

On February 14th, Trump grabbed the spotlight again. “The President has never asked me to do anything in a criminal case. AG Barr,” he tweeted. “This doesn’t mean that I do not have, as President, the legal right to do so, I do, but I have so far chosen not to!”

What’s gotten lost in the controversy is the hypocrisy of the self-righteousness among the Stone case’s prosecutors, and their bosses. The dueling sentencing recommendations show how easy it is to manipulate punishment in America’s federal courts. All it takes is a little addition here, or a little subtraction there.

Bipartisan-agreed guidelines informed Stone’s sentencing

The case’s career prosecutors arrived at their recommendation of 7 to 9 years in prison by tacking on what are known as enhancements under the federal Sentencing Guidelines. In doing so, they more than doubled the prison time Stone faced. But their bosses used a different formula by leaving out the enhancements to arrive at 37 to 46 months.

The US Sentencing Guidelines were created in the late 1980s as part of a law supported by politicians of both parties who were terrified of being viewed as soft on crime before an electorate that was terrified of crime. The Guidelines are based on a system of points assigned to such factors as a defendant’s criminal history and details of the crime.

The Guidelines altered the balance of power in federal courts by stripping judges of their authority to determine appropriate punishment for a defendant. It didn’t take long for prosecutors to figure out how to predetermine the prison exposure a defendant would face by piling on the most charges that carry harsh penalties.

For decades, federal judges were required to follow the Guidelines. But in 2005, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Guidelines were no longer mandatory, but advisory. In reality, the Guidelines continue to dominate sentencing decisions by judges, and that’s why both groups of prosecutors spent so much effort on the math of punishment.

Stone’s prosecutors justified their harsher recommendation by relying on testimony about how he threatened a witness in ways that are reminiscent of some of the most memorable scenes in The Godfather movies, including:

- “Do a Pentangeli”: Stone told a witness that if he were subpoenaed to testify before Congress, he should take the same approach as Frank Pentangeli, a character in The Godfather, Part II, who initially provides incriminating evidence against mob boss Michael Corleone. The Don shows up in the hearing room with Pentangeli’s brother in an act of intimidation. Pentangeli receives the message and recants his testimony.

Stone often engaged in tough-guy hyperbole. The prosecutors said he badgered the same witness to invoke the Fifth Amendment and refuse to testify before the House Intelligence Committee, and threatened the man if he didn’t: “I’m going to take that dog away from you,” Stone wrote in an email, referring to the witness’s therapy dog.

The prosecutors said Stone also deserved a stiff sentence because he posted a photograph on Instagram of the judge, Amy Berman Jackson, “with a symbol that appears to be a crosshairs next to her head.”

The senior Justice officials made no reference to the Instagram post in their court filing. Instead, they sounded more like defense attorneys than prosecutors:

- They quoted a famous portion of a 1935 US Supreme Court decision that defines the ideal prosecutor as “the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done.”

- They criticized their subordinates for relying on enhancements—“while perhaps technically applicable”—to arrive at a sentence comparable to punishment that defendants in gang war cases receive.

- They quoted the recipient of Stone’s threats as saying, “I never in any way felt that Stone himself posed a direct physical threat to me or my dog.”

In the final scene of their filing, the senior Justice officials abandoned the 37-to-46 months calculation. They asked Judge Jackson to consider Stone’s age, health, and lack of a criminal past in arriving at a sentence. “Ultimately, the government defers to the Court as to what specific sentence is appropriate under the facts and circumstances of this case,” they wrote.

They begged for mercy.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/31WgLl6

About the author

Toni Locy – Washington and Lee University

Toni Locy – Washington and Lee University

Toni Locy is a professor of journalism at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va. She spent most of her 25-year career as a journalist reporting and writing about federal courts and law enforcement.