The Covid-19 pandemic has struck as America gears up for the 2020 presidential election. With restraints on social interactions now in place, a move to nationwide voting by mail has been suggested as a way to conduct the election fairly. Peter Miller writes that voting by mail has become more popular, especially in western states, but that this has taken time – time that we now do not have. He warns that there are many ways mail-in ballots can be invalidated, and that previous studies show that they are much less likely to be counted than those cast in person.

The Covid-19 pandemic has struck as America gears up for the 2020 presidential election. With restraints on social interactions now in place, a move to nationwide voting by mail has been suggested as a way to conduct the election fairly. Peter Miller writes that voting by mail has become more popular, especially in western states, but that this has taken time – time that we now do not have. He warns that there are many ways mail-in ballots can be invalidated, and that previous studies show that they are much less likely to be counted than those cast in person.

The spread of Covid-19 has had dramatic and far-reaching effects on all aspects of public life in America and abroad. Millions of people are now home-bound to limit the spread of this novel coronavirus. An astonishing 88 percent of respondents in a recent Pew Research Center poll reported that the outbreak has forced a change in their personal lives.

With an uncertain end to the social distancing in many places, questions and proposed solutions by the Brennan Center and others are emerging to address how to conduct elections this year. The same Pew poll also found that 66 percent of respondents would feel uncomfortable going to a polling place to vote. Voting by mail has been one proposal to conduct elections that has caught public attention. Many states are scrambling to send absentee voting applications to all registered voters in advance of primary elections this spring and summer and pondering whether the reform can be in place in time for November. The governing Law and Justice Party in Poland has, somewhat controversially, put forward a bill to allow the elderly or those with medical conditions to vote by mail in presidential elections in May. Is this voting system feasible to adopt on a national scale in the US, and so quickly?

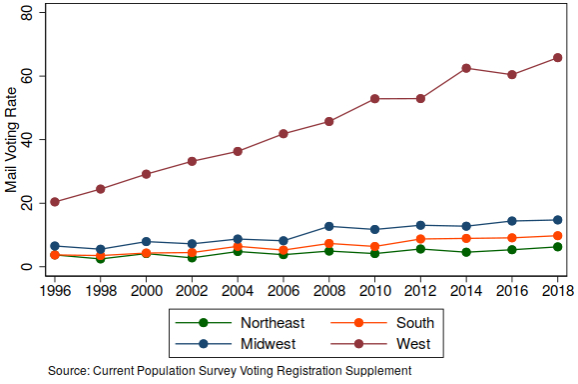

In a chapter in the new edition of the American Bar Association volume America Votes!, Paul Gronke and I describe the growth of mail and early in-person voting in American elections. We begin with the initial use of these reforms in the 1860s, follow them through the 1970s and 1980s and up to today, discussing how these reforms have becoming increasingly popular among voters and contested by the major parties. According to the Current Population Survey (CPS), 8 percent of ballots were cast by mail in 1996; by 2018 this had risen to 23 percent.

As states consider moving to all-mail elections, there are four points that may give pause to those who support moves to completely abandon polling places. First, mail ballots are largely used in the western states. About 66 percent of the votes in this region were cast by mail in 2018. By contrast, about 15 percent of ballots in the midwestern states were cast by mail in 2018, less than the mail voting rate in the west was in 1996.

Figure 1 – Mail voting by region

Second, this transition did not occur overnight. Oregon adopted mail ballots in 2000, but had been conducting off-cycle, special elections by mail since 1993 and the system proved popular among Oregonians. Counties in Washington state incrementally shifted to all-mail ballots between 1994 and 2011. Between 60 and 70 percent of Colorado voters cast their ballots by mail in the three elections prior to the state adopting an all-mail system in 2013. Outside of the west, mail voting is used by more than a quarter of the voters in only Florida, North Dakota, and Iowa. The experience of assuring equal access to and the integrity of an all-mail election is not easily gained in such a short period of time.

Third, all-mail elections still retain an option for the voter to return her ballot in-person, usually at an elections office or at a secure dropbox. In 2018, for example, 26.5 percent of ballots in Oregon were returned on election day. Eliminating the possibility of returning a ballot in-person will effectively disenfranchise the voters who are unable to return their ballots on time, like was the case in the Wisconsin primary where the Elections Commission reports 14.5 percent of absentee ballots have not been returned as of the morning of April 13.

“Vote by mail” by btwashburn is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Fourth, even when the voters are familiar with the process to vote by mail, there are multiple ways a mail ballot can be invalidated that do not apply to ballots cast in-person. The best study of how these ballots can be lost in an election comes from a study of the 2008 election by Charles Stewart, where he claims 7.6 million, or 20 percent, of mail ballots were lost at some point before being counted. The ballot could, for example, be lost in the mail either on its way to the voter or on the way back to the election officials. The voter may forget to put proper postage on the envelope or the signature on the ballot may not match the signature on file as well. Ned Foley estimates 8.2 percent of absentee ballots were not counted in 2018. While progress has been made to ensure all valid ballots are counted, mail ballots are still less likely to be counted than ballots cast in-person.

While mail ballots may be an appealing way to conduct an election under the conditions of COVID-19, there are complex administrative processes for states to fully consider before they abolish polling places entirely under any circumstances, and certainly not in the midst of a highly competitive presidential election.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2K7dOGp

About the author

Peter Miller – Brennan Center for Justice, New York University School of Law

Peter Miller – Brennan Center for Justice, New York University School of Law

Peter Miller is a redistricting researcher in the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law.