The Covid-19 pandemic has brought tensions between the US and China to the fore. In this interview, LSE US Centre Director Professor Peter Trubowitz comments that the crisis has reinforced the view that the US is too dependent on Chinese-based supply chains, and highlighted the United States’ lack of leadership in the world under President Trump’s ‘America First’ policies.

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought tensions between the US and China to the fore. In this interview, LSE US Centre Director Professor Peter Trubowitz comments that the crisis has reinforced the view that the US is too dependent on Chinese-based supply chains, and highlighted the United States’ lack of leadership in the world under President Trump’s ‘America First’ policies.

Has the pandemic accelerated the breakdown of relations between the US and China?

The pandemic has clearly heightened tensions between Beijing and Washington. Like most crises, this one has stressed existing fault lines and widened them. On the Chinese side, they are experiencing the first economic recession since market reforms unleashed explosive growth in the 1990s, with a 6.8 percent contraction in the first quarter of 2020. This has reminded them of how dependent their prosperity is on export markets, which have dried up. On the American side, it has reinforced the view that the US economy has become too dependent on supply chains that begin in or run through China. Whether the pandemic acts as an accelerator to fuel more nationalistic responses remains to be seen, but the early signs are not encouraging.

President Trump has referred to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus,” whilst Chinese state TV has stated it may have entered the country via the US military. Are both nations trying to gin up tensions to distract their publics from their own mishandling of the situation?

For leaders everywhere and at every level, the crisis is a test of trust and competency. Unfortunately, neither Xi Jinping nor Donald Trump have scored high marks with their own publics; both have suffered reputational damage. The worse the economy gets in China, the more incentive Chinese leaders, whose hold on power depends on strong economic growth, will have to stoke nationalism and divert public attention from their own missteps. In the US case, barring a very unlikely V-shaped recovery, Trump will not be able to run for reelection on the economy and will need another theme. He is already road-testing ads that blame China for the US economic crisis and that try to link Joe Biden to China for good measure.

Has the pandemic increased the likelihood of a conflict between America and China? Are we heading towards another cold war?

It is too early to say whether this will lead to another Cold War, but it is not too early to say that it has made an already strained relationship worse. Those tensions are likely to continue in the near term as domestic politics on both sides will make it harder to cooperate in any sustained, programmatic way in areas like the environment and public health where America and China do share common interests. Meanwhile, trade will remain dicey and perhaps, volatile. For today’s tensions to escalate into a full-blown Cold War, we would need to see a major ratcheting up of geopolitical tensions and military spending effectively aimed at each other.

Would it be correct to say that in recent years there has been a broad global view that American democracy is failing? If so, do you think this has played a role in enabling China to export its message and shape global conversations?

This is certainly a popular trope and it is a line that Beijing has been pushing since it seemed to get the health crisis in Wuhan under control. They have launched an international public relations campaign touting their success and by implication, pointing to the Trump administration’s poor record in handling the pandemic in the US and Washington’s lack of leadership internationally. I think the question is, will it wash? I doubt it. We already see a lot of pushback from international capitols, from Washington to London to Canberra. There are already calls for an international investigation into China’s handling of the pandemic in its earliest days — what the government knew, when it knew it, and what it did in response — and I think those calls will mount.

“made in china” by Michael Mandiberg is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

As the US has seemingly become more inward-looking during the crisis, China has attempted to fill the void to some extent and offer international assistance. Will we see China taking on more of America’s global role?

There has certainly been a lack of US international leadership during the crisis. That is remarkable in itself, at least if you compare it to how the US led in the case of HIV and Ebola. It is not surprising when one considers the Trump administration’s general America First approach to the world. By itself, it is unlikely to lead to a shift in international power dynamics, but it certainly has reinforced the view that the US is no longer willing to lead. How deeply engrained that view becomes depends partly on how Beijing plays its hand, and what happens in November in the US. If Donald Trump is reelected, then the view that the US is in full retreat will gain currency internationally. If Joe Biden is elected, then the world is likely to take a deep breath and say, “Okay, let’s see if Trump was a one off or indicative of a deeper shift in US foreign policy.”

How do you think the pandemic will impact international unity?

This is a defining moment for those who advocate economic openness, institutionalized cooperation, and multilateral governance. If not now, when? Unfortunately, we already see lots of signs of tension: between the US and China, the US and its European allies, and between members of the EU itself. There will be pressure to renationalize production and slow the flow of immigration. However, there will be counter pressures from industries that stand to lose billions of dollars of investment, people who count on being able to move freely across borders for business, education, and leisure, and from groups and people focused on problems like climate change and indeed, pandemic response, that can only be addressed through cooperation between countries. We are likely entering a new phase of the globalization drama, but it is not at all certain that it will be one defined by countries around the world building walls and pulling up drawbridges.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2VPARLt

About the author

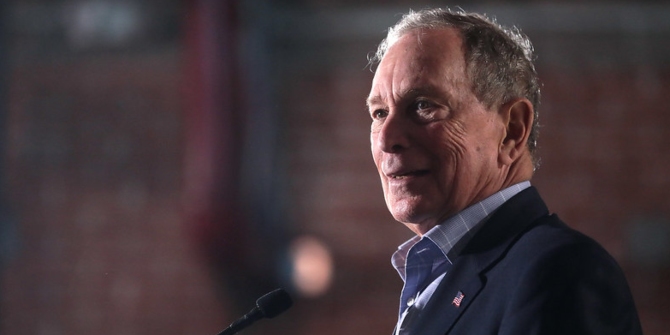

Peter Trubowitz – LSE US Centre

Peter Trubowitz – LSE US Centre

Peter Trubowitz is Professor of International Relations, and Director of the LSE’s US Centre. His main research interests are in the fields of international security and comparative foreign policy, with special focus on American grand strategy and foreign policy. He also writes and comments frequently on US party politics and elections and how they shape and are shaped by America’s changing place in the world.